“Chocolate chip cookie dough was always my favorite thing,” said Theresa, a bit mournfully. “I just shoveled it in, bite after bite.”

“How was it?” I asked her, prompting my client to evaluate her most recent dough-eating experience — the experience that had recently landed her in my office for food-issues counseling. After a deep breath, she replied, “You know what? It didn’t even taste good. I didn’t even like it.” Her voice was edged now not with longing, but with self-contempt and disgust.

Have you ever reached for a favorite food only to find it lacking? Have you noticed a particular food — or category of food — becoming less enjoyable over time? Have you eaten it anyway, even though the pleasure has dwindled into disappointment or numbness?

If, like Theresa, you’re wondering what happened to that cookie dough you used to enjoy so much, maybe it’s not the cookie dough (or equivalent food choice) that’s changed. Maybe it’s you — or more specifically, your “Pleasure Quotient.”

Direct Measure

Pleasure Quotient (or P.Q.) is a term I coined in my practice as a food-issues psychologist to describe and evaluate the whole complex of contributing factors that make or break a person’s eating pleasure. When a person has a high P.Q. experience, the act of eating and the taste of food feel great, and it results in total satisfaction. A low P.Q. experience is defined by unpleasant sensations, low consciousness and, often, lingering discomfort, frustration or shame.

The interesting thing is, the P.Q. of a given eating experience may have little or nothing to do with the food itself. That’s because while eating great food can increase your pleasure, if the other parts of your eating experience are low on the pleasure-quotient continuum, the food may not bring you any joy at all.

Let’s look at a few definitions that help explain this phenomenon: Pleasure is “an enjoyable sensation or emotion; satisfaction; delight.” Although sensation counts, emotion is the key word here. Emotion is “any strong feeling arising subjectively, rather than through conscious mental effort.”

“Arising subjectively” is key, because forcing or pursuing emotion usually results in an inauthentic experience — one tinged by disappointment and devoid of relief. So what is the recipe for increasing P.Q.? What are the ingredients when pleasure does arise and is plentiful? Let’s take a look at its components.

1. Hunger

The physical aspect of pleasure is the center of P.Q. Your level of hunger at the start of a meal will either contribute to or limit your eating pleasure. When hunger is just right, your P.Q. is primed; if you’re not hungry at all, even the best chocolate chip cookie won’t register as enjoyable. Likewise, if you’ve waited too long to eat, and your hunger is over the top, food won’t be as pleasurable and you’ll feel less satisfied.

Being satisfied at the end of a meal is a big part of P.Q. Think about your last Thanksgiving feast — or picture the next one. You know from experience that the discomfort of overeating can largely ruin the pleasure of the meal itself. By contrast, if you are “just-right hungry” at the start of a meal, and perfectly content at the end, your P.Q. is likely to be running high.

2. Senses and Quality

The sensory elements of food are essential ingredients in the pleasure of eating. How food smells, looks and sounds, its temperature and texture, all stimulate our senses, preparing us for the physical sensations of eating. Every one of our senses contributes to the quality of the experience.

The quality of food also contributes to or detracts from P.Q. Use low-quality, waxy, too-sweet generic chocolate chips in that favorite cookie recipe, and neither the dough nor the cookie will be memorable. Worse still is using prepared dough in pre-packaged tubes, which robs you of the smells, sensations and traditional ritual inherent in preparing the treat. Think there is no difference? Your palate will help you detect quality, but only if you’re paying attention.

3. Emotion and Thought

Besides being physically available to pleasure, we must be emotionally and intellectually ready to eat. When we are emotionally conflicted, we’re unlikely to feel much pleasure.

Recall a time when you were obligated to express emotion or behave in a way that didn’t jibe with your actual emotional state. For example, have you ever argued with your partner just before guests arrived, and then “played nice” (or at least acted civil) all evening for appearance’s sake? Perhaps you made the best of it, but the event was probably still a bit uneasy. Certainly, you wouldn’t describe it as pleasurable. And guess what — neither would your guests!

Conflicted emotional states are oddly contagious, and inherently disturbing for everyone around because they produce behavior that sends mixed messages. This is true in a social situation, but it is also true within the complex environment of your body: It’s hard to taste when your brain is distracted or in a fight-or-flight stress mode. It’s hard to digest food when your system is processing the biochemical byproducts of anger or grief.

When our emotional state is uncluttered and authentic, we can be attentive to the moment. Pleasure is thus more likely to occur, to be fully experienced, appreciated and noted.

Distracting thoughts can also reduce your chances of pleasurable eating. In our busy lives, distractions are plentiful. While we eat, we think about paying bills, finding a baby sitter, the fight we just had.

When we aren’t attentive to eating, we may gobble or rush and miss the very elements that could produce pleasure. We can also miss cues that we are not, in fact, enjoying our food at all.

4. Company

The company you keep affects your Pleasure Quotient too, whether you dine with others or alone. This aspect of P.Q. relies on the emotional and intellectual states of all the parties. Only you can determine your own emotional and intellectual state. But you can always choose your dining companions.

Are you strongly influenced by the eating habits or attitudes of others? Are there individuals in whose company you tend to overeat or undereat, with whom you tend to take more or less pleasure in dining? Take note of how, and consider why.

Are you engaged in a conflict or an emotional muddle with one or more of your dining companions? Clearing your emotional plate before you fill your dinner plate will help you decide what and how much to serve yourself, and also enhance your eating pleasure. If you are feeling conflicted or upset, you might need to clear the air with your companion(s), or allow your emotional state to pass before you eat. Or you might try dining alone, which can be as pleasurable as dining with loved ones. Meals, even ordinary ones, that are celebrations of life and self-respect are more pleasurable than meals taken for granted in barely noticed company.

5. Environment

Cluttered, chaotic space can negatively influence your P.Q. Think about great restaurants: The environment is always impeccable. There’s a reason for that: Visual beauty and atmospheric aesthetics all contribute to the P.Q.

Even if you live simply, you can create atmosphere. When the kitchen table is cluttered with mail, newspapers, toys and food packaging, attention is distracted. Clear the table, set the table, light a candle — and voila! — your P.Q. improves substantially.

6. Meaning/Purpose

The final aspect of P.Q. is meaning, or purpose. The purpose you seek depends on the state of all the other aspects of P.Q.

One of the ultimate determinants of eating pleasure is the reason — the “why” — behind our eating. If through eating we are pursuing relief from unpleasant emotions like boredom, loneliness, anger or sadness, what happens? Food doesn’t bring relief. Nor does it bring pleasure. If we are distracted by worries and thoughts that are out of our control, even the finest meal will bring little reward.

On the other hand, under the right circumstances, even the simplest of trail meals can produce a high P.Q. If you’ve got perfect hunger, a clear head, upbeat emotions and good company (even your own) and are surrounded by the splendor of nature, even a peanut butter and jelly sandwich can become a delectable and satisfying feast.

7. Knowing What Works

Understanding the P.Q. concept won’t spare you every eating misstep, nor should it prevent you from enjoying the occasional indulgence. The point is not to achieve perfection or claim some “genius” level P.Q., after all. It is to truly enjoy your food — to get the most out of all the pleasure, nutrition and satisfaction it has to offer, while at the same time respecting your body, heart and mind.

The “D.I.E.T.” Plan

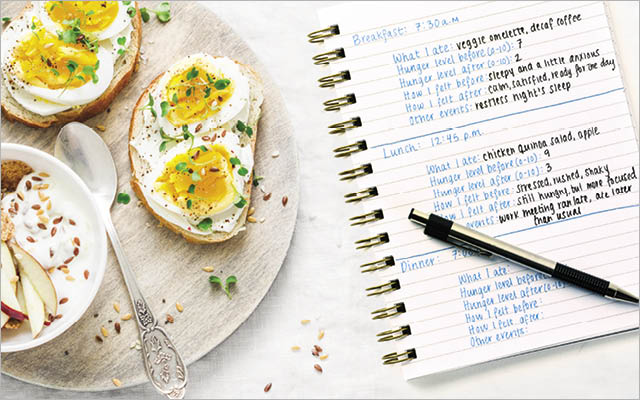

I suggest to many of my clients that they develop their own approach to D.I.E.T. (Discipline in Eating Things). Consider integrating the following ideas into your eating guidelines:

- Eat when you’re hungry, and only when you’re hungry — not just when food appears, when others are eating, or when the clock strikes.

- Assess the quality of food before you eat it: Does this stuff deserve to go into and become part of your body?

- Develop a more discerning palate: Become a picky eater! Eat only what will satisfy — what tastes and feels really good to you.

- Clear your emotional plate before you eat: Avoid eating when you are restless, bored, angry, fearful or disturbed. Seeking emotional relief with food does not work.

- Limit distractions: Enlist the ancient motto “Age quad agis” — Latin for “Do what you are doing.”

- Tune in to the total experience: Focus on what you enjoy about your companions, notice what parts of the environment appeal to you. Let yourself be “fed” by the company and conversation as well as by the food being served.

- Set your intent: Before you take your first bite, identify what you want to get out of your eating experience by asking yourself, “What’s the meaning of this meal?”

This Post Has 0 Comments