Sections to explore:

- What is physical hunger?

- How does chronic dieting affect appetite?

- Does fatigue make us feel hungrier?

- Why do I crave salty food?

- Is there a difference between hunger and cravings?

- Why do I sometimes feel hungry immediately after a big meal?

- Why do I lose my appetite when I’m anxious, angry, or sad?

- Why do I crave sugar when I’m upset?

- How can I tell if I’m hungry for something other than food?

Alexandra Jamieson was in her mid-20s when she started experiencing chronic migraines, as well as anxiety and depression. She decided to try healing herself with diet. When she embraced veganism, she found immediate relief from her symptoms. She went on to cocreate Super Size Me, the Oscar-nominated documentary about the toxic effects of fast food on one man’s body, which led her to public acclaim as a vegan chef and wellness coach.

Fast-forward 10 years. Jamieson was 35, and she had begun getting her period every two weeks. She felt exhausted and drained. She tried to heal herself with food as she’d done before, using all available tools within veganism to balance her hormones and restore her energy. None of it helped.

Around this time, she had started to crave red meat. When she went out to dinner with friends, she would secretly hunger for their steaks while she dutifully ate a tofu salad.

At first, she resisted, realizing the risks to her highly public reputation as a vegan chef. But Jamieson eventually chose to listen to her body and discovered that her cravings were telling her what she needed. After she began eating animal products — at home with the curtains drawn — she felt her strength and energy return.

“My body said, Yes, more of that, please,” she recalls. She soon learned she’d been severely anemic.

Her choice to eat meat led to brutal online criticism and the loss of close friendships. But she didn’t regret her decision, concluding that “the diet that heals you may not be the diet that sustains you.”

“The diet that heals you may not be the diet that sustains you.”

Jamieson didn’t renounce veganism; she just discovered that it was no longer right for her. Importantly, she also learned that she had been ignoring other signals from her body. Honoring her food cravings led her to a deeper understanding of what else she was missing in her life, including physical intimacy.

Her story, which she shares in her book Women, Food, and Desire, shows that food cravings can reveal more than just nutritional deficits. Hunger and other cravings carry important information about almost all our needs.

Based on her own experience, Jamieson suggests that we ask ourselves, without judgment, What is the information I’m getting from this craving? It can help us learn a lot about our physical, mental, and emotional needs and desires.

That said, it’s not always so easy to understand our appetites. Most of us have been conditioned to think of hunger as something to be disciplined, not acknowledged. (This is especially, but not exclusively, true for women.)

We may repress or ignore hunger and cravings, distrusting and denying the signals. We might struggle to separate eating from anxieties about weight and size, or we might take refuge in disordered eating for a feeling of control.

All this resistance to our body’s messages can lead to some real bewilderment about what our hunger is trying to say. Do we need food, or different food? Do we need comfort? Do we want to celebrate or connect? Are we really, really tired? Are we bored?

Hunger can mean all these things and more.

To help clear up some of this confusion, we asked some experts to clarify the meaning of hunger — as well as the many things it might be trying to tell us. They also share why these messages are so important. Learning to hear and decipher our hunger cues allows us to work with, rather than against, our bodies and their diverse needs.

What is physical hunger?

The sensation of hunger is a signal from your body to the brain to find food. Your stomach might growl, you may feel irritable, and you are likely to become preoccupied with food until you eat.

The whole process is stimulated by the release of hormones. “Many metabolic hormones help regulate hunger, but two of the biggest are leptin and ghrelin,” explains functional-medicine dietitian Katherine Wohl, RDN, IFNCP. When you’re hungry, your stomach produces ghrelin and sends it to the brain — it’s like the warning light flashing on the fuel gauge in your car, alerting you that you’re running low.

Once you’ve eaten, leptin kicks in. Also known as the satiety hormone, leptin is secreted by fat cells, telling your brain that you’ve stored enough energy now, and that it can call off the alarm. “When we eat when we’re hungry, and stop when we’re full, we get those cues in a really harmonious way,” Wohl explains.

If there’s a hormonal disruption, however, the cues can go haywire.

Insulin is another hormone that regulates metabolism, and it can become dysregulated when there’s more glucose in the system than the body can handle. The stress hormone cortisol can also upend the hunger-signaling process. When metabolic hormones are out of balance, Wohl says, “we lose our body’s innate wisdom that helps tell us when we’re hungry and when we’re full.”

(To learn more about insulin and cortisol, go to “How to Balance Your Hormones.”)

How does chronic dieting affect appetite?

Missing a meal now and then won’t harm your hunger cues, but routinely repressing or ignoring them can scramble the body’s signals.

When we chronically resist physical hunger, as with dieting or disordered eating, it’s almost as if the body throws up its hands. “The body is wired for survival,” says psychologist and eating-disorder specialist Rachel Millner, PsyD. “If we’re not eating day after day, it will stop sending out cues, such as stomach growling or shakiness. This is like the body saying, ‘This person isn’t feeding me consistently, so I’m not going to show those more obvious signs of hunger anymore.’”

Missing a meal now and then won’t harm your hunger cues, but routinely repressing or ignoring them can scramble the body’s signals.

At this point, metabolism slows and blood pressure drops. “The body needs food to stay alive, and if it’s not getting enough, it’s going to slow down and quiet everything else to try and preserve life,” explains Millner. “You will likely feel fatigue and will be thinking about food more often.” This confusion of signals can make it hard to tell when you’re hungry or when you’re full.

But the body is wise, and it’s possible to reteach it to feel hunger. In the same way it learns to start shutting down when it’s being deprived, it will start waking up when food is available again.

In her work with clients recovering from eating disorders, Millner first asks them to eat predictably and consistently throughout the day — whether they’re aware of hunger or not. “Start to build a trusting relationship with the body, where every couple of hours it starts to learn that food is coming.”

Over time, this consistency helps rebuild appetite. Your body recognizes that sending hunger signals is a good use of energy, because it results in being fed.

Does fatigue make us feel hungrier?

Sleep deprivation can throw your hunger hormones out of whack. Ghrelin surges, making us hungrier. Leptin sputters, making it harder to feel sated. And stress hormones like cortisol flood the bloodstream.

This is the brain’s way of putting out an SOS for more fuel. It’s trying to compensate for the lack of sleep with other sources of energy, preferably “any kind of energy source that will deliver the most immediate surge of usable fuel,” explains Jamieson.

That energy source is often sugar. “What do you crave when you’re low on sleep?” Wohl asks. “You crave sugar and carbs so that you can get that energy back. Studies show that sleeping less than seven hours can increase your cravings for sweet foods — but getting extra sleep, even if it’s small amounts, can reduce cravings.”

Why do I crave salty foods?

Salty foods are often highly palatable, but salt cravings can be about more than just taste. They may be a signal that the body is experiencing chronic stress, which taxes the adrenal glands by constantly calling on them to produce more cortisol.

“When people crave salt, it’s often either that their blood pressure is low or they have some adrenal dysfunction,” explains integrative physician Frank Lipman, MD. “Often when those hormones are off, there’s a craving for salt.” (For more on managing cortisol and adrenal health, see “How to Balance Your Cortisol Levels Naturally.”)

Salt is a mineral we lose when we sweat, so we might also crave it after an intense workout or a sauna. Pediatrician Jan Chozen Bays, MD, once saw a 1-year-old child who was “so floppy that he was unable to sit up.” His parents had just driven through 100-degree heat, hydrating him with distilled water, which is stripped of minerals, including sodium.

Upon hearing this, Chozen Bays went to the cafeteria and returned with a bag of chips. Immediately, the boy sat up, grabbed the chips, and started eating. “He had ‘heard’ his cells calling out for sodium chloride (salt), and as soon as he saw it, he responded,” she explains in her book Mindful Eating.

Is there a difference between hunger and cravings?

In general, hunger builds gradually, while cravings come on suddenly. And while hunger is more open-minded, cravings tend to target one food specifically.

Sometimes hunger is described as physical and a craving as emotional, but Millner doesn’t believe that emotional hunger is any less legitimate.

In general, hunger builds gradually, while cravings come on suddenly. And while hunger is more open-minded, cravings tend to target one food specifically.

A craving for chocolate, for example, may be a sign that you’re feeling lonely or bored and your body knows the comforting hit of dopamine it provides will give you a lift.

“Many of us have connections with certain foods to childhood or memories,” she says. “Sometimes we might crave certain foods based on that.”

Why do I lose my appetite when I’m anxious, angry, or sad?

When you’re anxious or afraid, your body detects a threat. The sympathetic nervous system responds by flooding your body with cortisol, preparing it to react. In this state, digestive processes are suppressed as blood flow is redirected toward bigger interior muscles, ones that enable you to put up your dukes or run like the wind. This is not the time to think about food, after all: Your body is convinced that it’s time to escape danger.

Not eating may be part of a coping strategy that helps numb emotions we’d rather not experience.

Sometimes, appetite loss also occurs when we feel sad. Some healthcare providers see this as an early warning sign of depression: A loss of interest in food may indicate a broader disinterest in regular activities.

Not eating, Millner says, may be part of a coping strategy that helps numb emotions we’d rather not experience. “For some people, eating less can dull some of the feelings.”

Why do I sometimes feel hungry immediately after a big meal?

It may have something to do with what you ate — or didn’t eat. A meal without much fiber or protein won’t keep you full for long. Protein takes longer to digest than carbohydrates, and fiber helps slow the digestive process — all of which helps keep you feeling sated. Fast-burning, low-fiber carbohydrates, such as white bread, pasta, and pizza, won’t keep you feeling full.

Protein also reduces ghrelin levels and increases leptin sensitivity. “Protein is an incredibly satiating macronutrient,” Wohl says.

Similarly, a meal containing a lot of sugar (think French toast with syrup and a large cup of sweetened coffee) can set off an insulin reaction that leaves you feeling not just hungry but cranky. You might then crave protein or fat, a sign that your body is struggling to get macronutrients that can satisfy it. (To learn more about how excess insulin can provoke hunger, see “Hungry No More.”)

Finally, you may just need water. “Sometimes when people think they’re hungry . . . they’re actually thirsty,” notes Lipman.

Why do I crave sugar when I’m upset?

Sometimes when we crave sugar, we’re just trying to feel better — and sweet foods do provide a temporary boost. “[Sweet] substances release opioids . . . into our bloodstream, and when those chemicals bind with the receptors in our brain, we experience an intense sensation of pleasure — maybe even get a little high,” explains Jamieson.

A habit of turning to sweets can become an unconscious strategy for mitigating difficult feelings, Wohl says. “You naturally want to tamp down that stress response with carbs and sugar and foods that mitigate those feelings in the moment — but it backfires [in the] long term, actually making the stress response worse.”

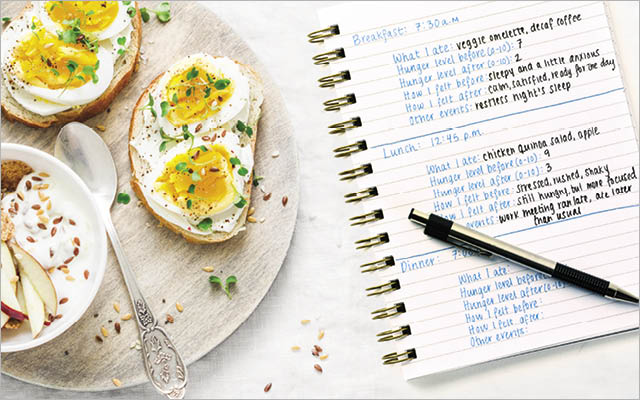

How can I tell if I’m hungry for something other than food?

Deciphering hunger signals may take some practice. But “the body has its own wisdom and can tell us a lot about what it requires if we are able to listen,” suggests Chozen Bays.

In her book Mindful Eating, she describes something called “heart hunger,” which has little to do with food. “Most unbalanced relationships with food are caused by being unaware of heart hunger,” she offers. “No food can ever satisfy this form of hunger. To satisfy it, we must learn how to nourish our hearts.”

Most of us need to learn to identify heart hunger before we can satisfy it. Chozen Bays recommends the following exercises:

- Make a list of the foods you eat when you are sad or lonely.

- Notice when you feel an impulse to have a snack or a drink between meals.

- Stop and observe the emotions and thoughts you were having just before the impulse arose.

- Then, if you have the snack or drink, pay attention. Does anything change?

If you notice that what you’re really feeling is loneliness, try addressing it directly by calling a friend. Or if you discover that you’re genuinely sad, wrap yourself in a blanket and feel sad. This is how you feed heart hunger — by giving the heart what it really wants.

Finally, if you discover that what you’re hungry for really is food, then put some food on a plate, sit down, and enjoy a meal that will nourish you on every level.

This article originally appeared as “What Your Hunger Is Trying to Tell You” in the May 2023 issue of Experience Life.

This Post Has 2 Comments

I found this short article to be especially interesting and helpful. I have an unhealthy relationship with food and wine and have had for decades. Though I have acceptable weight and body composition I continuously struggle with food and body image. Frequently I wish I did not have to bother with food at all. I would love regular articles such as this one.

Rings true.