Comedian Lily Tomlin once quipped that the trouble with the rat race was that even if you won, you were still a rat. Though many of us are forever angling for a promotion, a higher-paying job and more socioeconomic status, when we reach the end-points of our self-designed mazes, we aren’t always happy with the little squares of cheese we thought we were after. Sometimes, instead of making our lives better, the so-called rewards of success only add to our problems.

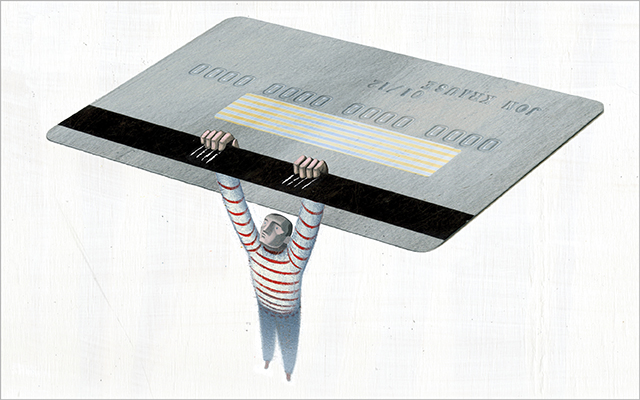

The promotions are nice, but we’re working so many hours we barely see our families. We spend more time in traffic and on airplanes, and we spend more money on the clothes and cars that seem suited to that position. We pay for all sorts of timesaving conveniences that let us pour still more time into our careers. And then we spend heavily on vacations and expensive trinkets that make our too-tough work lives seem worth the trouble. Ironically, our quest for financial success isn’t only physically and mentally exhausting – it’s downright expensive.

Dollars and Sense

So if our pursuit of the almighty dollar isn’t making us happy, what might? In Your Money or Your Life, Vicki Robin and Joe Dominguez put forth an innovative concept: Your goal, they said, shouldn’t be to accumulate as much money as possible, but rather to shift your relationship with money so that your spending patterns directly align with your highest priorities.

By refocusing on what’s truly important, whether that’s time with family and friends, a better quality of life, or a favorite cause, it is possible for us to spend far less on short-lived luxuries and conveniences, the authors asserted, and wind up much more satisfied in the bargain.

Robin and Dominguez’s book, which suggested a step-by-step, awareness-raising approach for evaluating and shifting our daily spending habits, became a national bestseller. Today, it continues to transform people’s lives. Readers who have put the book’s principles into practice avow that, yes, it’s possible to live well, and very happily, on far less.

Published in the wake of the 1980s, an age associated with material excess and slavish devotion to corporate climbing, Your Money or Your Life presaged much of today’s popular talk about simplicity. And while in the intervening years simplicity has become a consumer trend in its own right (witness the product-laden magazine Real Simple), the concept of choosing to live more simply, and of consciously reducing the size of one’s own consumer footprint, has also continued to resonate, spawning Web sites, magazines and college courses around the country. The Simple Living Network Web site lists more than 500 resources to help people learn about – and live – the simple life.

Your Money or Your Life has been far-reaching in its influence, says Wanda Urbanska, author of several books on simplicity and host and producer of Simple Living with Wanda Urbanska. “I think the book is as relevant now as it was 13 years ago,” she says. “People need help recognizing how powerfully their choices about money affect their lives. Too often, we just throw money around without really thinking. We don’t pay attention to how our consumer lifestyle is bogging us down.”

Trading “Life-Energy” for Money

Short of winning the lottery, there are few quick routes to financial freedom in today’s world. But for those willing to make conscious choices, a longer and passable path does exist, according to Dave Wampler, a board member and spokesperson for the New Road Map Foundation, which promotes principles outlined in Your Money or Your Life.

“The unique thing this book did was lay out nine simple, specific things you can do to live a more financially intelligent life,” Wampler says. “It’s a focused, sequential, cumulative program that’s also synergistic. If you do all the steps, the final result is greater than the sum of its parts.”

One of the book’s foundational tools is a formula that helps readers realize that their money and their time are inextricably linked. “Money,” the authors wrote, “is something we choose to trade for life-energy.”

If you work a typical 40-hour workweek and make $800 a week, the math seems straightforward: You trade one hour of your time for $20. But the truth is actually more complicated than that.

You probably spend time and money on many things directly related to your job, like work clothes, commuting, parking and lunches. If you have kids in daycare, that expense alone can run you thousands of dollars each year.

And then there are all sorts of tangential job-related expenses – the new car you buy so you fit in with your colleagues, or the takeout meal you purchase each evening because you’re too exhausted to prepare dinner. If your job is stressful, you may have the added costs of seeing a counselor – or worse, dealing with stress-related medical problems.

If you tally up just the time it takes you to do all these things and add that to your 40-hour workweek, the number of hours you sacrifice to your job each week will likely balloon. Separately, add up the direct and indirect costs of having a job and subtract that from your $800-a-week paycheck. Then recalculate your earnings per hour (using that newly calculated hours-per-week figure). Chances are, your hourly wage has dropped significantly.

Consider the situation of Ben Patrick, a 29-year-old lawyer from Golden Valley, Minn. He regularly works 50 hours a week and takes home a $1,643-per-week paycheck. Roughly calculated, that’s just under $33 per hour. But factor in the time that Patrick spends commuting, preparing for work, attending work functions and decompressing from work-related stress, and the number of hours he devotes to work-related activities increases to 80 hours per week (See “The Cost of a Career,” below). With adjustments for parking costs, gas expenses, meal expenditures and clothing outlays, his weekly salary drops $143 to $1,491. All told, when time and expenses are recalculated, Patrick earns $18.64 an hour – little more than half of what he thought he was making.

Real-Cost Accounting

Once you’ve got your true earnings figured out, you’ll probably begin to reevaluate how you want to spend that hard-won cash. After all, when you find out that a $100 item is costing, say, not three, but more like six hours of your life-energy, the tradeoff may not seem as appealing.

Finding out where your money goes takes more than quick mental accounting, however, since it’s easy to forget a few dollars here and there – and those dollars quickly add up. In Your Money or Your Life, Robin and Dominguez advise carrying a notebook with you in your purse or pocket. “Keep track of every cent that comes into or goes out of your life,” they write. “It’s the best way to become conscious of how money actually comes and goes in your life as opposed to how you think it comes and goes.”

That daily latte is only a few dollars, but at $5 (or more) a day, excluding weekends, it’s a $1,300-per-year expense.

You’ll likely discover that you spend much more money than you realize on expenses beyond your basic necessities. That daily latte is only a few dollars, but at $5 (or more) a day, excluding weekends, it’s a $1,300-per-year expense. Similarly, the latest technological gizmo may seem essential when you see it in the store, but assess how many other gadgets you’ve bought in the past year. Did they really change your life? How many times have you worn those I’m-gonna-splurge $200 slacks? Were they worth the life-hours you spent working for them?

Even when it comes to expenditures for things you really do value, it’s worth considering alternative means that allow you to get them for less. Carolyn Hilles, 53, a librarian who lives in Milton, Mass., says she has always considered herself a frugal person. But until recently, she still made her share of impulse purchases. An avid reader who has bookish friends, she had rarely given much though to her frequent book purchases – she and her friends, she admits, considered them sacred. But Your Money or Your Life made Hilles rethink her approach to spending money on books.

She realized she didn’t need to own every book she read, since she rarely read them twice. Instead of dropping money in every bookstore she visited, Hilles began borrowing books from libraries and friends. She decided to put the funds that she saved toward experiences and things that gave her repeated enjoyment.

“It may seem strange to look at your life through the lens of how you spend money,” Hilles says. “But you earn money in order to live a particular lifestyle. So it’s worth asking: Does how you spend your money really dovetail with how you want to spend your time?

Living Deliberately

When Joseph Beckenbach III, a senior software engineer living outside San Gabriel, Calif., first read Your Money or Your Life, he began recording how he spent every cent he earned. The evaluation ultimately led Beckenbach, 39, and his wife to cut many expenses. And when they decided to buy a new car, they saved up for it and then paid for the automobile in cash to avoid a hefty interest charge.

But they didn’t cut back just to cut back: They wanted to be able to live on just one income when they had children. “With each expense, we asked ourselves whether this was making our dream of one parent at home more possible or less possible. If the answer was ‘less possible,’ we figured out how to change our spending habits to put that amount toward ‘more possible,'” he says.

In some cases, that meant making compromises, such as living with old furniture a little longer than they might have liked. But as Beckenbach points out: “It’s easy to say ‘no’ to one thing when it means saying ‘yes’ to another possibility.”

This article has been updated and originally appeared as “The Smart Money.”

This Post Has 0 Comments