Few exercisers give stretching its due. Though flexibility is considered a major component of fitness, most gym-goers scrap stretching in favor of strength and cardiovascular work when they’re pressed for time (which turns out to be quite often).

But the issue isn’t just whether or not you’re stretching. Your results also depend on how and when you’re stretching. (See “Stretch and Reach: The Unexaggerated Truth About Stretching”) And lately, an innovative partner-assisted stretching-and-strengthening technique called resistance stretching has been gaining currency among cutting-edge trainers, professional athletes and fitness enthusiasts as a way to increase performance — sometimes in remarkably short order.

In the 2008 Summer Olympics, for example, then-41-year-old swimmer Dara Torres referred to resistance stretching as the “secret weapon” that allowed her to capture three silver medals. Tennis pro Martina Hingis reportedly increased the speed of her serve by 10 miles per hour after just a few sessions. And numerous internationally competitive endurance athletes, speed skaters and gymnasts have seen similarly marked improvements.

Far from a simple tweak to standard-operating stretching procedures, resistance stretching is about as different from the familiar rec-center stretching methods as a full-body kettlebell workout is from a leisurely stroll. Turning the traditional notion of stretching on its head, a person doing resistance stretching will forcefully contract — rather than relax — the target muscle group as a resistance-stretching practitioner moves his muscles from a contracted to a lengthened position.

“Contracting your muscles as you stretch them will teach you to be more comfortable at that range of motion,” says Pavel Tsatsouline, author of Relax Into Stretch: Instant Flexibility Through Mastering Muscle Tension. “It desensitizes the protective mechanism that prevents your muscles from extending to their full length, thus resulting in rapid gains in flexibility, strength and function.”

Like the many different styles of yoga and martial arts, resistance stretching can take various forms, each of which emphasizes different aspects of the same set of principles. Many coaches and practitioners consider Resistance Flexibility and Strength Training (RFST), founded by Olympic coach Bob Cooley, to be the most refined version of resistance stretching, and Cooley’s book, The Genius of Flexibility: The Smart Way to Stretch and Strengthen Your Body, to be its seminal text. But practitioners of Ki-Hara Resistance Stretching, developed by Torres’s trainers, have also had excellent results with clients.

Though RFST and Ki-Hara are currently available only in specialized studios, you can still get a taste of the technique at your local gym, where most of the personal trainers are likely to be familiar with Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation (PNF), a “second cousin” to resistance stretching, originally developed in the 1940s.

But whether you do PNF at your local gym or resistance stretching with a certified specialist, you can garner long-lasting improvements in flexibility and surprising increases in strength and performance.

Vive La Resistance

Resistance stretching is a form of eccentric training, in which a muscle goes from a shortened, contracted position to a lengthened one while under some kind of load. In that sense, many of the movements resemble the “lowering” phase of some familiar strength-training exercises.

A basic resistance stretch a practitioner might do for the biceps, for instance, is similar to the eccentric portion of a dumbbell curl: The person being stretched starts with his wrist close to his shoulder and resists while the practitioner slowly straightens his arm by pulling down on his wrist.

But the effects of resistance stretching go beyond what can be accomplished with a few heavy dumbbells. Because the limbs naturally move in an arcing motion (rather than in a straight line), and because muscles are stronger in some positions and weaker in others, practitioners must continually shift the direction and force of the pressure they apply to make each stretch as safe and effective as possible.

Most people can lower two to eight times more weight than they can lift, meaning that if you can curl 25 pounds, you might be able to lower — or “uncurl” — as much as 200.

Throughout the session, the practitioner makes constant, tiny adjustments to accommodate the person’s natural movement patterns. RFST practitioners, for example, sometimes perform as many as a thousand distinct stretches in the course of an hourlong session. Resistance stretching can thus resemble a kind of rigorous physical “conversation” between practitioner and client.

Most people can lower two to eight times more weight than they can lift, Cooley explains, meaning that if you can curl 25 pounds, you might be able to lower — or “uncurl” — as much as 200. So generating a true, maximal eccentric contraction, particularly in the larger, stronger muscle groups, can require some serious effort from both the practitioner and the client. Using resistance stretching on the hamstrings of world-class gymnast Epke Zonderland, for instance, requires “five or six guys,” Cooley explains. “And they’re exhausted after a few minutes.”

Fascia Facts

So why all the straining? Aren’t we taught in most stretching classes to relax? And how does working a muscle along its entire range of motion — rather than only in a “stretched” position — improve its flexibility? Why not just reach for our toes, hold for 30 seconds, and be done with it?

Standard stretches reduce tension in muscles and thereby enhance flexibility. But the forceful, full-range eccentric muscle contractions of a resistance-stretching session don’t simply relax and lengthen muscle and connective tissues. They also help break down scar tissue, muscle adhesions and the fibers of connective tissue called fascia, all of which can significantly limit both flexibility and strength.

Fascia can be incredibly tough — not unlike the material that makes up the elastic resistance bands you see in the gym — so breaking it up requires a little more effort than a traditional gym-class stretch-and-reach drill. “With resistance stretching, the muscle fibers are grabbing each other as you pull them apart,” says Tom Longo, owner of StretchWorks in Palo Alto, Calif., and an RFST practitioner. This friction between elongating fibers “pulls tense muscle fibers apart and helps break up adhesive tissue.”

Research by Cooley and others has borne out this theory: Following a session with a practitioner, the bloodstream is flooded with spent connective tissue. That may sound a little scary, but resistance stretching does no damage to the essential tissues in your muscles, tendons and ligaments. Only the extraneous fascia in and around the muscles — which can inhibit proper contraction and efficient movement — gets flushed out as the contracting muscle fibers rub against one another.

If you have trouble touching your toes, the problem might not in fact be tight hamstrings, but rather quadriceps — front-thigh muscles — that can’t fully shorten and contract.

Deposits of scar tissue and excess fascia can build up in places we don’t expect, or even notice. We tend to stretch the areas of our bodies where we feel tight and stiff, and leave other areas alone, Cooley notes. But his experience indicates that we’re often unable to feel the areas most in need of intense stretching and bodywork because the scar tissue and connective fascia (which grows in and around these areas to protect them) have limited sensory capacity.

“If you want to know where your body needs the most work, don’t pay attention to the places that feel tight,” Cooley says. “Home in on the areas of the body you can’t feel, and work on them. Stretching is all about the fascia, and fascia has no connection to your brain.”

In fact, our physiological “dead zones” are often found in the muscles opposite the areas we think need the most work. So if you have trouble touching your toes, for instance, the problem might not in fact be tight hamstrings, but rather quadriceps — front-thigh muscles — that can’t fully shorten and contract. Since stretching a muscle also improves its ability to contract, stretching your quads will help make the forward-bend position easier.

By the same token, if the hip flexors are short and tight, resistance stretching of the hamstrings and glutes (which extend the hips) can help ease the problem.

Stretching for Strength

A commonly held weight-room belief is that the flexibility of a muscle has little to do with its strength. Stretching, after all, trains muscles to elongate, whereas strength training requires them to shorten. But Cooley has found that if you develop a muscle’s “true flexibility” — its ability to maximally contract along its entire range of motion — then the strength of the muscle increases proportionately.

“If you’re a basketball player, and you increase the true flexibility of your lower-body muscles by 10 percent, that means a matching increase in your vertical jump!”

And the speed of muscle contraction can increase with resistance stretching as well, which translates into greater functional power — in the water, on the field and on the ice.

“I’ve found that most people I work with — average people and elite athletes alike — use just 40 to 60 percent of their current muscle potential,” says Longo. “A lot of the muscle mass they have is not available to create force, since muscles are too tense or are trapped within dense fascia or have scar tissue damage. Tense or trapped muscles also create biomechanical imbalances, which cause inefficient movement patterns.” Longo has found that his work with clients reduces these inefficiencies, freeing up more strength to use in life and on the playing field.

Ironman veteran Gina Kehr, a client of Longo’s, says that her resistance-stretching sessions completely transformed her swimming stroke: “It was insanely freeing,” Kehr says. “My shoulders could move so much more easily, and my swimming became a hundred percent easier. I was always told that to get better I needed to strengthen my muscles more and more. But I was already strong and had plenty of muscle mass, so I knew there had to be a better, smarter way.” Resistance stretching made her significantly stronger — not by building more muscle mass, but by helping her to use the muscles she already had to maximum effect.

Building strength along a muscle’s full range of motion can also help prevent injury. “You’re most likely to get injured when your body gets into a position where you have no strength or control, such as when you slip on a patch of ice,” says Tsatsouline. “But by training your muscles to contract while stretching, you get stronger even in more extreme, stretched positions.” That makes you less likely to lose control and get hurt when mishaps occur.

Proceed With Caution

Resisting all the pushing and pulling of a resistance-stretching session may sound painful — perhaps even dangerous. And the partner-assisted version is certainly not something you should casually experiment with. “If you’re going to do this kind of stretching, make sure that you’re working with someone who really knows what they’re doing,” says Stacy Ingraham, PhD, a professor of kinesiology at the University of Minnesota. “There’s not a lot of room for error.”

Still, Longo points out that these techniques have a remarkable safety record when compared with other stretching systems: “Improper conventional stretching can sometimes lead to joints that are hypermobile [too flexible] and therefore unstable.” But the muscle tension created by the resistance-stretching client tells the practitioner exactly how far to stretch a given muscle group. “When the client stops contracting a muscle or the muscle stops contracting for any number of reasons, I stop stretching it,” he says. As an additional precaution, Cooley often monitors the muscle opposite the one being stretched — the triceps when stretching the biceps, for example — to make sure it’s contracting as well. “As long as that balancing muscle keeps shortening,” he says, “the person will not overstretch.”

Resistance-stretching sessions can be intense, however: “My first session wasn’t as bad as childbirth, but it was close,” laughs Kehr, a mother of two. But after their sessions, most clients feel wonderfully relaxed, especially if they’ve been suffering from acute pain. Kehr, for instance, who initially sought out Longo to help treat a groin injury, was pain-free by the end of the first session. And after an initial breaking-in period, most clients experience little residual soreness at all. “I work with athletes who have to compete the next day,” says Cooley. “They can’t afford to be sore.”

Resistance stretching isn’t a cure-all, of course, and it won’t take the place of a solid fitness program. “Sometimes I tell people, ‘I can’t stretch your muscles until you make them stronger,’” says Longo. But these methods can serve as an excellent complement to strength and cardiovascular conditioning. Longo says that both he and Cooley see a lot of exceptionally strong, fit people — pro athletes and weekend warriors alike. Many of them have hit a wall in building additional strength, fitness and skill in their sport, however, and find that resistance stretching can help propel them to the next level.

“My average client is like a racecar driver who really wants to get faster, but the car he’s driving is out of tune,” he says. “Resistance stretching fixes his alignment. It balances the tires. It makes more cylinders fire more fully. It makes everything work together harmoniously, so the car can go twice as fast without working as hard. After a few months, it’s like he’s traded in his Volkswagen for a Ferrari. That’s what resistance stretching can do for your body.”

For a taste of how resistance stretching works, try these three self-stretches. They address the muscle groups most likely to become inflexible in our desk-bound society:

- upper back

- hamstrings

- hip flexors and quadriceps

“Self-stretching is a vital part of resistance stretching,” says Tom Longo, a practitioner from Palo Alto, Calif., who has his clients perform daily self-stretches between their weekly 75-minute one-on-one sessions. Longo suggests foam rolling the target muscles prior to stretching to increase blood flow, and advises breathing as openly and powerfully as possible throughout resistance-stretching exercises.

Resistance Stretching Exercises

For a taste of how resistance stretching works, try these three self-stretches. They address the muscle groups most likely to become inflexible in our desk-bound society: upper back, hamstrings, hip flexors and quadriceps.

“Self-stretching is a vital part of resistance stretching,” says Tom Longo, a practitioner from Palo Alto, Calif., who has his clients perform daily self-stretches between their weekly 75-minute one-on-one sessions. Longo suggests foam rolling the target muscles prior to stretching to increase blood flow, and advises breathing as openly and powerfully as possible throughout resistance-stretching exercises.

Rear-Shoulder Stretch

- Kneel with your left knee down and your right foot on the floor in front of you.

- Brace your left elbow against the outside of your right knee, bend your left arm approximately 90 degrees, and place your right hand on the back of your left wrist.

- Exerting constant downward pressure on the back of the wrist with your right hand, yet resisting that pressure at the same time, fully rotate your left arm forward and back.

- Taking about five seconds per repetition, cycle back and forth between these two positions, keeping the pressure on your left arm as if locked in a back-and-forth arm-wrestling match.

- Perform six to eight repetitions on both sides.

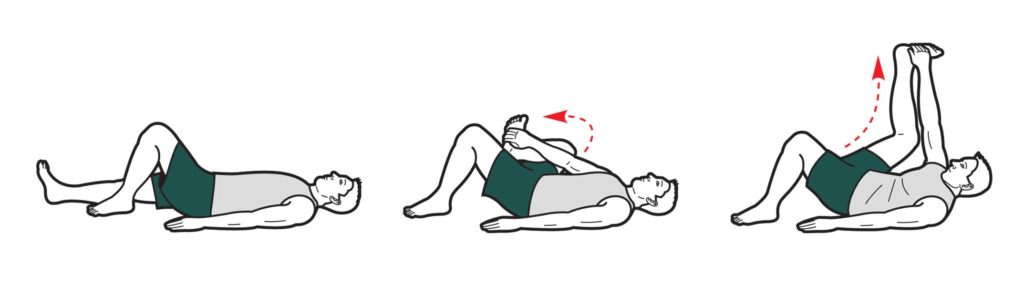

Hamstring Stretch

- Lie on your back, bend your left leg and place your left foot flat on the floor.

- Lift your right knee toward your chest, reach up with your right hand and grasp the inside arch of your right foot, allowing your right knee to travel to the outside of your torso. Your head and upper back may need to come off the floor to accomplish this. (Loop a yoga strap around your foot if necessary.)

- Slowly alternate between flexing and extending your right leg. Use your hand and arm to strongly resist both motions.

- Perform six to eight repetitions with each leg, taking five seconds per full repetition.

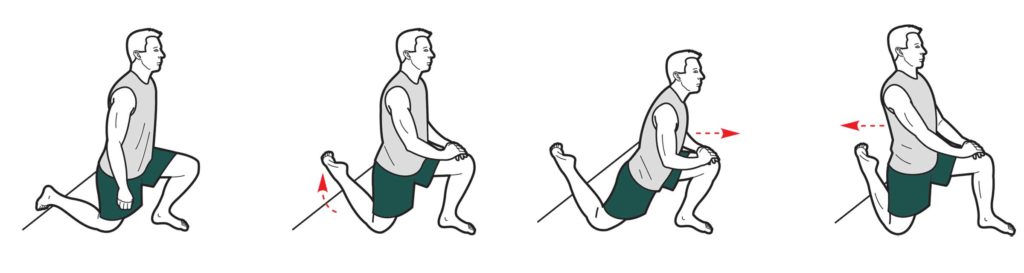

Quadriceps/Hip-Flexor Stretch

- Place a gym mat next to a wall. Face away from the wall and kneel on the pad with your right knee down and your left foot flat on the floor in front of you.

- Slide backward toward the wall, pointing the toes of your right foot toward the ceiling. Keeping your right knee on the floor, inch your foot up the wall behind you until you feel a comfortable stretch in the front of the right thigh. (If this position hurts your right foot, place a small pad between your foot and the wall.)

- Place both hands on your left knee and extend your back into an upright posture.

- While maintaining a fully upright posture, forcefully press the top of your right foot into the wall and rock your body forward and back, keeping your torso directly above your hips throughout the movement. Each full repetition should take about five seconds.

- Repeat for six to eight repetitions per side.

For a list of qualified RFST practitioners, visit www.meridianstretching.com. For a list of practitioners of the Ki-Hara Method, visit www.innovativebodysolutions.com.

This article originally appeared as “Resistance Is Not Futile” in the December 2010 issue of Experience Life.

This Post Has 0 Comments