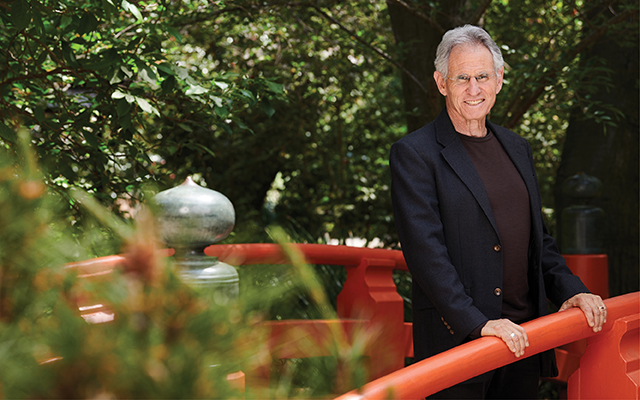

Finding an antidote to the drivers of distraction — our fears, our judgments, our feelings — has been a long-standing project for Jon Kabat-Zinn, PhD. Even as a child, the man who’s now recognized as a pioneer in mindfulness meditation felt something was off about the way living seemed focused on external rather than internal forces.

“We’re actually imprisoned by what we’re unconscious of,” he explains. “Not a moment goes by in which we don’t like this rather than that or want this more than that. Mindfulness is awareness that arises from paying attention on purpose in the present moment, nonjudgmentally, so you begin to notice how insanely judgmental we are.”

He began meditating in 1966 as a grad student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) while working toward his doctorate in molecular biology.

During the Vietnam War, he became a staunch antiwar activist. In 1969, while leading students in protest to halt MIT’s role in making nuclear warheads, he called out the United States’ larger distractions, fears, and judgments, stating that we were approaching a disaster of major proportions.

Seeing the mind–body connection as essential to individual — and global — health and well-being led Kabat-Zinn to combine Buddhist teachings in meditation with medicine to treat chronically ill patients. In 1979, he spearheaded the formation of the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center.

At the heart of the clinic’s practices is Kabat-Zinn’s Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program, which teaches patients to use innate resources to respond to stress, pain, and illness. More than 20,000 people have completed the eight-week MBSR program, while countless others have been introduced to contemplative practices via Kabat-Zinn’s online guided meditations and many celebrated books, including Wherever You Go, There You Are.

“Mindfulness is a skill anyone can learn,” the 74-year-old writes. “What is required is a willingness to look deeply at one’s present moments, no matter what they hold, in a spirit of generosity, kindness toward oneself, and openness toward what might be possible.”

Experience Life | We are living in highly distracted times as a result of rapid technological advances and the convenience of our devices. Why is mindfulness in the midst of all of this a radical act?

Jon Kabat-Zinn | It’s not just a radical act, but a radical act of sanity to drop into the domain of being as opposed to doing.

To stop all the doing for a moment and ask yourself Who’s doing all this doing and why? is tantamount to being who you already are, so no effort is required. It’s not like you have to discover who you are, but more like you have to recover who you are.

We are being driven to distraction by our own increasingly sophisticated and seductively addictive technologies. Not just the hardware, but Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and all the ways that we have of looking in on each other’s lives and then creating narratives about how great they are and how not so great we are.

As a result, we end up pretending we’re great or tracking how many people like our recent post — and if they don’t like it, it’s a bummer and we go into a quasi-depression. All of this checking winds up enslaving us to those channels.

I just came back from China, and the word for mindfulness in Chinese is niàn. The word is composed of the ideogram for “now” above the ideogram for “heart.” Interestingly, the word for “anger” is the ideogram for “slave” over the ideogram for “heart.”

In this instance at least, that reflects some degree of wisdom in the language itself. We are being enslaved by our impulses to look outside of ourselves for affirmation that we’re OK, or that there’s something more interesting than now that we should be checking because maybe this moment’s not good enough. This is a kind of prescription for insanity and for deep health problems on multiple levels.

EL | How does mindfulness affect our health and lives?

JKZ | When we’re mindlessly moving along, zoning through the present moment to get to better moments, we start believing the narratives we carry. We create stories about who we are, where we’re going, what’s in our favor or against us, how stressed or frightened we are, and how inadequate and unworthy we are. We focus on these thoughts so much that we often believe those assessments of our lives as truths rather than as thoughts.

But they’re just thoughts, and this is where liberation lies. Becoming mindful of our thoughts as just thoughts can free us from the oppression of our unexamined thinking minds. This is powerful for improving mental health, especially if someone’s dealing with anxiety or depression.

The more embodied we are in awareness, the more we’re capable of feeling appropriately what’s here to be felt — anger, sadness, and happiness — and managing our emotional reactivity. We begin having greater clarity and can act and feel with more sensitivity, empathy, and compassion.

EL | How has mindfulness research changed since you began studying it, and what are some of the findings?

JKZ | When I published my first paper on mindfulness and chronic pain in 1982, it was the only paper on the subject in the mainstream medical literature. Research was slow for a long time, but over the next 15 to 20 years, with studies from a small number of groups, people started to get more interested. Now the curve of the number of papers per year in the medical and scientific literature with the word “mindfulness” in the title is growing exponentially. In 2017, around 670 papers were published.

That doesn’t mean the data is all equally good or convincing, but it indicates that the evidence base for the effectiveness of mindfulness in different domains is growing rapidly. One of the reasons is the development of three new scientific fields: neuroplasticity, epigenetics, and the effects of stress on cellular aging and on our telomeres.

Neuroscience is showing that mindfulness practices can restructure brain regions over even eight weeks of MBSR, and perhaps in even less time, making some areas more dense (such as the hippocampus, involved in learning and memory) and others less dense (such as the amygdala, involved in threat reactivity).

Mindfulness also seems to drive what is called functional connectivity in the brain, strengthening communication between different brain regions that, when communicating better, can play a more positive role, for instance, in emotional reactivity under stress and impulse control.

Epigenetic studies are showing that meditation practices can also up-regulate and down-regulate the synthesis and activity of hundreds of genes in our genome, many of which seem to be involved with inflammatory processes that are now thought to underlie many chronic diseases, including cancer.

In terms of biological aging, it is well known that stress accelerates the shortening of our telomeres, the repeat DNA subunits at the ends of all of our chromosomes, which shorten every time one of our cells undergoes mitosis. Work by Liz Blackburn, who won the Nobel Prize for such research, and her colleague Elissa Epel, has shown in some studies that intensive meditation can slow down that shortening of the telomeres and possibly reverse it.

EL | What are technology companies doing to change the designs of hardware and software, and how can mindfulness help us use technology more wisely?

JKZ | Many people in Silicon Valley — including those who invented these technologies — don’t want their own kids near their fantastic inventions. I understand that Steve Jobs, for example, wouldn’t let his kids use his hardware.

Tony Fadell, who headed Apple’s iPod and iPhone teams, is into mindfulness and is developing a counter-revolutionary approach to the slavery we’ve given ourselves over to voluntarily with these devices.

Mindfulness is a powerful practice for becoming aware of the impulse to check your phone. Can you notice the impulse to check in arrive? Can you let it come, let it go, and not check your phone and live your life in that moment? If not, you’re just filling your life up with stuff that’s not your life.

This Post Has 0 Comments