Let us light a hempen candle in memory of hippies, for history has not treated them kindly. They’re often remembered for their regrettable bell-bottoms, their fulsome tie-dye, and little else. As if to illustrate this point, my third grader came back from camp last summer with a chant that posited the various life paths one could have taken besides going to camp, including being a hippie: “Love and peace, my hair is full of grease!”

Hippie food has fared no better, even though it’s what many of us were raised on.

When Jonathan Kauffman was growing up Mennonite in Elkhart, Ind. — hardly a community known for Summer of Love abandon — his family ate like many earthy types in 1970s America: hippie-style.

“My parents were part of a garden collective, and we ate a lot of lentil stews, yogurt, sprouts, wheat germ — we even had a moment of carob,” Kauffman recalls.

Eventually, his parents grew out of their hippie phase, and Kauffman went on to become the most elite of eaters: a restaurant critic in San Francisco.

That’s where the two of us met and bonded over childhood memories of looking askance at our parents’ wheat germ — though my side-gazing happened in the heart of New York City. To this day I think of wheat germ as a food product that really goes a step too far. Keep the hard, albeit nutritious, germ of wheat and toss away the soft middle? You might as well have an apple pie made only of peels. (I wish I had been able to concoct this metaphoric rebuke in third grade.)

But Kauffman went beyond mere reminiscing. He decided to investigate that passage in American food history to discover its roots and unveil its enduring effects.

“Just as I started thinking about hippie food as a unique occurrence and looking into the origins of it, I realized that many of the restaurants that had been an important part of it were dying,” says Kauffman.

Indeed, several of the vegetarian, vegan, and feminist eateries that thrived in California’s Bay Area in the 1970s have disappeared. Around the country, some classics — Sunlight Cafe in Seattle; Seva in Ann Arbor, Mich.; Bloodroot in Bridgeport, Conn. — live on, though most have moved beyond their hippie roots. “I thought, I’d better capture these stories before they’re gone,” Kauffman says.

So he got out there, tracking down hippie-food history. He located the food co-ops that predated and inspired modern-day health-food stores, such as Whole Foods; talked with the activists who helped craft the official USDA organics program; and explored why Asian burritos make so much sense to American eaters when, say, Czech burritos don’t.

The book that resulted? Hippie Food: How Back-to-the-Landers, Longhairs, and Revolutionaries Changed the Way We Eat.

Beyond Woodstock

As Kauffman and I know from our childhoods, hippie food wasn’t restricted to Woodstock potlucks. Its reach was wide, springing seemingly out of thin air during the late 1960s and early 1970s and leaving its mark on family dinners across the country. The fact that yogurt was able to leap from weird fringe food to grocery-store mainstay in the blink of an eye may be due to hippie food’s roots in other longstanding American traditions.

During the 18th century, for example, our country’s deep culture of religious freedom produced Seventh Day Adventists, Protestants who believed in healthy eating and a vegetarian diet. Notably, it was hippies on the spiritual trail to India and Asia — returning with lentils and saag paneer — who later brought such fare to the Adventists.

In the early 20th century, immigrants in the upper Midwest — the same ones who founded farming cooperatives such as Land O’Lakes — introduced their co-op traditions from northern Europe. The co-op food markets of the 1960s and ’70s owed their heritage to this farming distribution model, as well as to the consumer-owned businesses that emerged from the political and economic turmoil of the 1930s. Hippie-era co-ops demonstrated that, with volunteer labor and bulk bins of oats, you didn’t need much capital to open a grocery store.

“There were also a few books that were hugely influential, like Diet for a Small Planet and a Seventh Day Adventist vegetarian book called Ten Talents Cookbook,” Kauffman notes.

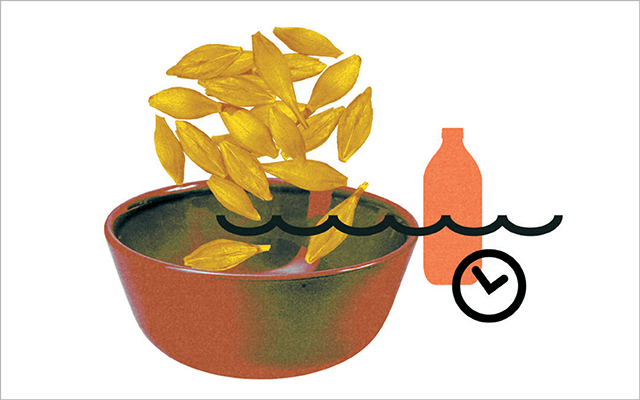

Thence came brown-rice-and-tempeh bowls sprinkled with sunflower seeds and seasoned with liquid aminos — a quintessential hippie staple that went out of fashion only to return to popularity in many of today’s healthy-eating circles.

“Much of this food was kept alive in the kitchens of people of that generation, but the media-driven food culture moved on,” Kauffman observes. “Baking whole-wheat bread went out of fashion for 20 or 30 years, replaced by these crunchy French and Italian breads. But lately, with the return of heirloom grains, we see something close again to what the hippies were doing.”

From Tofu Chili to Korean Tacos

No, hippie food was not vanquished. If anything, it’s come back stronger, though under a somewhat different guise. The same people who started co-ops and championed a back-to-the-land ethos for small farmers went on to create the certified-organic movement — which supports a market now valued at $43 billion annually.

“Even the way the hippies idealized very particular parts of the world, like Asia and Central America — you see that in our food today,” says Kauffman. Yesteryear’s hippie tofu chili cleared a path for today’s Korean tacos.

So, hippies, you win. I concede that you had more gastro-cultural impact than your Earth Shoes led us to believe. Indeed, as Kauffman promises to explain in his new book, hippies have even more to teach modern folk who survey our foods from the enlightened paradise of avocado toast and açaí smoothies.

“As Americans, we tend to believe that every new movement that comes out is the best thing that’s ever been thought of,” says Kauffman. “We jump from one food trend to the next because we’re so desperate for a food movement that will help us be fit and happy. But I think it’s instructive to look at food movements that came before.”

Because, as it turns out, peace, love, and bean sprouts weren’t such bad ideas after all.

This Post Has 0 Comments