Erosion is a natural geological process: the breaking down and carrying away of rocks by water, ice, wind, plants, animals, and other corrosive agents. It’s an essential part of being human, too, argues author and environmental activist Terry Tempest Williams.

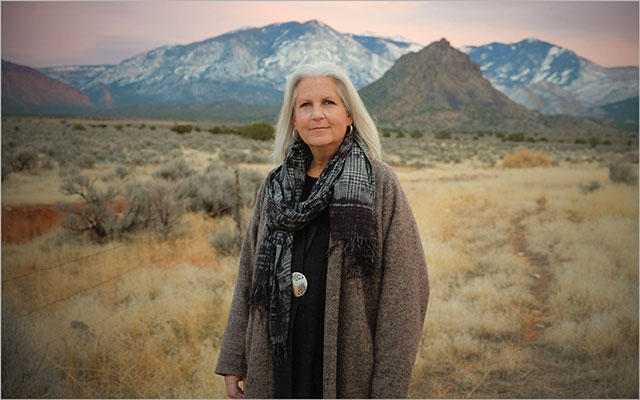

“Like the red rock desert before me, I, too, am eroding,” she notes while looking out the window of her home near Moab, Utah.

In her latest book, Erosion: Essays of Undoing, Williams explores what it means to witness not just the whittling away of America’s public lands, but also the gradual erosion of culture, democratic institutions and norms, trust, and the self.

“If the world is torn to pieces, I want to see what story I can find in fragmentation,” she writes.

The collection features tales of Williams’s own political resistance to the gutting of public lands as well as the fallout from her activism. Forced out of her job at the University of Utah in 2016 — ending a relationship with the school that dated to her undergraduate days in the 1970s — she is now writer-in-residence at Harvard Divinity School.

It chronicles her anger over the spoiling of the natural world and threats to the Endangered Species Act, as well as her grief over the death of her brother Dan. He sent Williams a text message shortly before he died by suicide in which he said he was eroding.

While our losses may feel unbearable, the acclaimed author of Refuge and When Women Were Birds recommends looking into, instead of away from, the pain we feel. “If we don’t understand our pain then we can’t heal,” she says. “These essays are my howl.”

Experience Life | What inspired you to write about erosion?

Terry Tempest Williams | I live in an erosional landscape. From my porch, the La Sal Mountains rise to the south. To the west lies Porcupine Rim, a bitten horizon running along the parameter of the sky. To the north, the Colorado River, running red with sediment, cuts through the canyons. To the east, you have Castleton Tower, a 400-foot Wingate monolith, one of the tallest freestanding towers in the world.

So, erosion is what I see physically, and at this moment in time, erosion is what we’re experiencing on a daily basis politically — the erosion of democracy, the erosion of decency, the erosion of science, the erosion of truth. And I wondered how, during a weathering of the land, a weathering of norms, a weathering of the self, do we find the strength to not look away, but begin instead to understand what beauty erosion can create?

EL | Your books help readers see that contradictions can offer a path for moving forward or for being more present. Can you talk about the paradox of erosion?

TTW | What I see is that we’re watching our democracy erode, but at the same time, look at what’s evolving: a heightened sense of consciousness and a deep sense of responsibility and engagement. And it transcends politics.

In this moment of climate and ecological crisis, we are being asked to deeply question everything that we’ve taken for granted. What does it mean to a planetary consciousness to know that we’ve lost a billion animals in the fires in Australia? What does it mean when we continue to see these floods or famine that are the seedbed of war?

What does it mean to live in Utah in a constant state of drought? And what does it mean to weather this global pandemic as we are returned to our homes in this planetary pause? I wonder who we will be when we emerge.

EL | What do you tell people who say that they grieve for what’s been lost and don’t know what to do about it?

TTW | I think if we can know what that ache in our heart is rooted in — that it’s rooted in love — then it gives us the strength to act. Grief and love are siblings. This is the heart of Erosion.

And as I travel around the country, I see hope. People are rising in their own home ground, in their own region. When it comes to nickel mining near the Boundary Waters or the oil and gas pipelines in the Colorado Plateau, they are asking who benefits, and they see that it’s not the people and it’s certainly not the land and its creatures.

The Native communities adjacent to these big oil and gas developments — the methane gas is going straight into their communities. Pollution is going into the water table and people are drinking it. They’re getting sick or dying, and so, who benefits? It’s not really about bringing jobs; it’s about profits.

Democracy demands our participation, and engagement, for me, is a prayer. I believe that each of us holds a piece of the mosaic of a healthy planet, and that it is for each of us to find out what that piece is and to figure out how to offer that up in the name of community.

EL | Where do you turn when you’re feeling depleted, lost in grief or anger, or in need of guidance?

TTW | Several things come to mind. One, I make a point when I’m home, and whenever I can, wherever I am, to see the sunrise and the sunset every day. Having those two pauses of honoring the rising and setting sun and being aware of where the moon is grounds me.

I actually learned that from observing the prairie dog [while writing Finding Beauty in a Broken World]. In their communities, I watched them at dawn stand in front of their burrows with their paws placed together, watching the sunrise. And then, every night, no matter where they were, they would run back to their burrows, and before they would go underground again, they would face the setting sun, and put their paws together. I now call them “prayer dogs,” and that became my spiritual practice.

The second thing is that I seek my elders. Whether it’s my father at 86; Linda Asher, a literary translator, at 87; artist Mary Frank at 87; poet Etel Adnan at 95; or Beatrice Monti della Corte, who runs the Santa Maddalena retreat center in Italy — she’s 94.

The third — so this would be my trilogy — is walking the land and being in nature to remind me that I’m part of this larger whole, a community both human and wild.

EL | After you were fired for your political activism, what has it meant to be teaching again at Harvard?

TTW | I feel grateful to have a job. I feel liberated in terms of my own expression, to be in a community that welcomes deep thought and contemplation. It’s something that the divinity school fosters in their curriculum. There’s a powerful community here of people who are committed to social justice and spiritual reflection.

I love my students and am humbled by them. They’re taking risks and asking the tough questions. I love teaching, because in the act of teaching, I am in the act of learning.

This Post Has 0 Comments