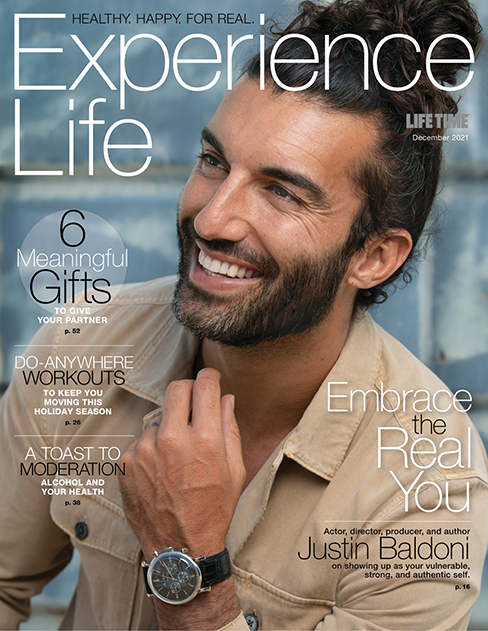

Justin Baldoni is tired of performing.

The 37-year-old filmmaker isn’t retiring from Hollywood — his latest project, Clouds, was released on Disney+ in October 2020. But in his book, Man Enough: Undefining My Masculinity, Baldoni writes about giving up a different kind of performance: our culture’s definition of what it means to be a man.

Those societal expectations — to always be strong, brave, successful, and stoic, to name a few — set what Baldoni calls an “impossibly high and unachievable mark of masculinity. . . . It was as if the bar were set too high and I couldn’t reach it, or more like the box was built too small and not all of me could fit inside it.”

Those societal expectations — to always be strong, brave, successful, and stoic, to name a few — set what Baldoni calls an “impossibly high and unachievable mark of masculinity. . . . It was as if the bar were set too high and I couldn’t reach it, or more like the box was built too small and not all of me could fit inside it.”

That socialization leads a lot of men to feel as if they’re lacking — and it simultaneously denies them an outlet to express their insecurity. “And if you’re not allowed to be insecure, you’re not allowed to cry, you’re not allowed to be vulnerable, then all of that gets buried until you don’t even know it exists,” he explains. “And how are we ever going to heal if we don’t know how we feel?”

Man Enough chronicles Baldoni’s own healing — what he calls “the journey from inside the box to inside myself” — in an effort to encourage others to undertake the difficult work of questioning long-held cultural standards that tell us who we’re supposed to be. “You are good,” he writes, “inherently and intrinsically good. . . . Who you are, as you are, is enough.”

Q&A With Justin Baldoni

Experience Life | You write that our culture presents young boys with a false choice. Tell us what you mean by that.

Justin Baldoni | We teach boys to fit inside of a predetermined box. They have to be tough, impermeable, resilient. They can’t question authority or ask for help. They can’t display compassion, empathy, or emotional intelligence, which our culture frames as feminine.

So young boys are faced with this false choice where they have to choose their masculinity at the expense of their humanity, because what makes them human are those “feminine” qualities.

I didn’t realize until recently that even the language that was reinforced in me made me unconsciously distrust women. When we tell a boy to “man up,” to not act like a girl, we’re conditioning him to hate the “feminine” parts of himself. That language sticks with us. It follows us into our friendships and marriages and workplaces.

It comes down to allowing everyone to be the fullest version of themselves, however they identify. We should all be allowed to be who we are — and we shouldn’t be forced to choose between being accepted and being our full selves.

EL | What does it mean to you to “undefine” masculinity?

JB | When I first started doing this work, I thought I was on a journey to redefine masculinity. I think it was very surprising for people that someone like me — a white, straight, cisgendered man who had fallen into some success — was willing to challenge the patriarchy and to have uncomfortable conversations about things that aren’t working for our society.

But who am I to get to redefine anything? I’m just a guy who recognizes that the system I was raised in has hurt me more than it’s helped me. It’s helped me materially, but it’s hurt me emotionally.

And everywhere I look, I see that the system is broken and that other people are suffering — and hurt people hurt people. And I want to heal, because healed people can then heal people.

More than that, I realized that by redefining masculinity — by creating a new box — I would just be creating more suffering, because boxes are the very thing that hurt us. It’s the undefinition that can set us free.

EL | You often speak on your podcast, Man Enough, about the importance of calling people in rather than calling them out. Why do you think that approach is so important?

JB | These conversations can be really tricky to navigate in today’s culture. There are a lot of people with immense privilege who don’t know how to talk about things like social justice. And what I think we often fail to recognize is that while oppressors are benefiting from an unjust system, they’re not bad people. And what oppressors don’t realize is that the fact of their privilege triggers a painful response from marginalized communities who have been trying forever to make their voices heard.

What I see happening right now is that instead of building bridges, we’re building emotional walls. There’s incredible work happening in social justice and activism, but the gap is widening between the folks who really need to hear those messages and those who are willing to hear them.

What’s scary about our current climate is that a social-media post can literally alter the course of someone’s life. A lot of people are walking on eggshells when they need to be in the conversation — they need to be at the table listening.

I think what we need as a society is the ability to sit at the table and listen, and to hold space for an individual who’s hurting, to hear their story and recognize their pain. So, what I’m trying to do is call in people like me — people with immense privilege — and help them understand the conversation, so the burden of education isn’t on the oppressed group.

Then, ideally, they need to be willing to hear how their actions are hurting people, how they’re benefiting from an unjust system, and not take that personally.

EL | You write quite a bit about “the hard work of heart work.” What does that phrase mean to you?

JB | I believe that one of the purposes of life is to grow — and not your bank account or your muscle size. I’m talking about emotional and spiritual growth, which, at the end of our lives, is all that matters.

There’s an old saying that the longest distance that a man will ever travel is the distance between his head and his heart. And men, from a very early age, are taught to sever that head–heart connection out of self-preservation.

I think we all need to reconnect our heads and hearts and take that gusto for material growth and apply it inside. But there’s no monetary value for that growth, no tangible way to measure it.

You can measure it in how much love you give, how happy you are, how grateful you feel for what you have. That’s the growth that will allow you to be more present for your family, to show up fully in your relationships, to apologize when you’re wrong, or to sit at the table when it’s uncomfortable.

That’s what I mean by the hard work of heart work. And that doesn’t start with social media. It starts with an audience of one in the mirror.

EL | How has that work changed the way you show up in your own life?

JB | I’m practicing radical honesty in my life, which means not shying away from the things that scare me and being willing to have real conversations with my wife, with my children, with my parents.

If we could all learn to be honest with each other, I think our culture would change overnight. Our children could grow up without this unrealistic expectation of gender and this weight of needing to be enough, and they could see that their parents — the people who love them the most — are deeply flawed, complicated human beings. And that they too will grow up to be deeply flawed and complicated.

It’s in that imperfection, I believe, that we find perfection. That’s where the humanity is. The poet Rumi wrote that the wound is where the light enters you. We’re all wounded; therefore, we’re all full of light.

This article originally appeared as “Self-Reflections” in the December 2021 issue of Experience Life.

This Post Has One Comment

Great article. I struggle however with Baldoni’s “undefine masculinity” approach. It’s an approach similar to “dismantle masculinity.” The premise being that any definition of masculinity is inherently bad, limiting or boxing. The problem with that approach is that it leaves an empty space where boys and men have no direction in which to turn when they do wish to exhibit positive masculinity. We are pushing a narrative that suggests men should dispense with all masculinity. We’ve worked rightfully hard to redefine what it means to be a woman and what that gender role can be by promoting flexibility and positivity. We still can redefine what it means to be a man in positive ways. Don’t leave a vacuum. Boys and men want to do and be good. Promote positive masculinity. Not undefined.