Lack of energy was never a concern for Heidi Raschke. As an undergraduate at the University of Minnesota, Raschke easily juggled a full course load with a part-time job and an internship at the campus newspaper. Then, in her senior year, her reserves started to run low. Normally an “A” student, Raschke couldn’t concentrate and her grades slipped. “I felt overwhelmed,” she remembers. “I was tired all the time.” Raschke’s mood wasn’t helped by the fact that she was suddenly carrying extra weight. “I’d run six miles several times a week and bike to school every day,” she says. “Nothing helped.”

At first Raschke assumed that depression was the root cause of her problems. A therapist prescribed Prozac, and both the medication and therapy seemed to help initially. But just over a year later, her physical symptoms returned with a vengeance. One night she slept for 19 hours straight. “That scared the hell out of me,” she says.

Raschke made an appointment with her doctor, who immediately ordered a blood test. The results confirmed she was suffering from Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis, an autoimmune disease that had damaged her thyroid gland. Raschke’s thyroid function was depressed – a condition, called hypothyroidism, that her doctor said was likely irreversible.

Until her diagnosis, Raschke had never even thought about her thyroid. Suddenly, it seemed to have control over every part of her life. This led Raschke to ponder a question that will likely be posed by a growing number of Americans in coming years: How can such a comparatively tiny gland have such a giant impact?

The Body’s Gas Pedal

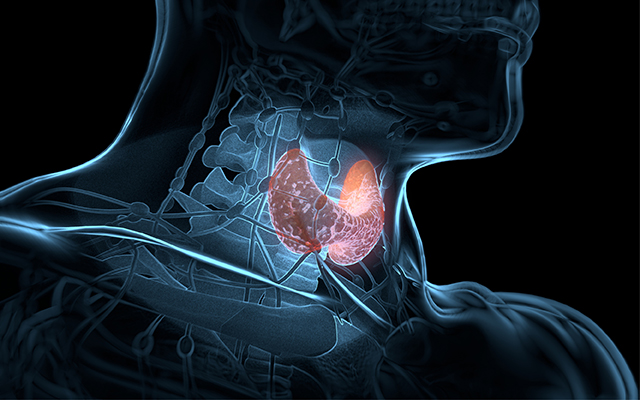

A healthy thyroid is important to everyone’s well-being. A butterfly-shaped gland located at the front of the neck between the Adam’s apple and the collarbone, the thyroid produces several hormones, two of which – triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) – are vital to a person’s health. These hormones help oxygen get into cells and make your thyroid the master gland of your body’s metabolism.

“The thyroid is the gas pedal for distributing energy throughout the body,” says Richard L. Shames, MD, coauthor, with his wife, Karilee Halo Shames, RN, PhD, of Thyroid Power: 10 Steps to Total Health. “Thyroid hormone keeps the body working at the right speed.”

When an individual’s thyroid hormone levels decrease, explains Shames, the activity in his or her body’s cells decreases, too. As a result, the person may feel emotionally and physically drained and may also gain weight, even as his or her appetite wanes.

Hypothyroid disorders are extremely common. According to the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), one in 10 Americans – more than the number of Americans with diabetes and cancer combined – suffer from thyroid disease, more than half of them undiagnosed.

The most common cause of thyroid disease in the United States is Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis, a chronic autoimmune condition that results when the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues. The thyroid can also produce elevated levels of thyroid hormones (hyperthyroidism), usually as the result of a less-common autoimmune condition known as Graves’ disease.

In the case of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis, the immune cells that usually fight off infection and colds attack the thyroid instead. The damaged thyroid loses function, resulting in a variety of symptoms including fatigue, weight gain, forgetfulness, depression, constipation, dry skin, and cold hands and feet. Left untreated, hypothyroidism can lead to more serious health consequences, such as elevated cholesterol, heart disease, osteoporosis and infertility.

“There is a huge population of people who are gaining weight and are depressed and exhausted, and they aren’t being treated properly.”

Hypothyroidism runs in families and is five to eight times more common in women than in men. The elderly are also at increased risk for the disease. The AACE estimates that by age 60, as many as 17 percent of women and 9 percent of men have an underactive thyroid.

“There is a huge population of people who are gaining weight and are depressed and exhausted, and they aren’t being treated properly,” says Mary Shomon, who was diagnosed with hypothyroidism in 1995 and is today a patient advocate and the author of Living Well With Hypothyroidism: What Your Doctor Doesn’t Tell You That You Need to Know. Shomon and other advocates, including many doctors, want more attention paid to thyroid disorders, including treatment options for people with low, but not necessarily disease-level, thyroid function.

“Something doesn’t have to be at the level of a disease for it to be a problem,” says Laura Thompson, PhD, a naturopathic endocrinologist and director of the Southern California Institute of Clinical Nutrition. “There tend to be a lot of mysterious symptoms that people can’t explain that turn out to be subclinical thyroid imbalances. Inability to lose weight, depression, irregular menstrual cycles, severe PMS, menopause problems – all can be related to the thyroid.”

Recently, official hypothyroid diagnosis guidelines were adjusted downward (see “The Numbers Game” below). The change, which received a great deal of media coverage, was designed to help doctors more accurately identify and treat the large number of hypothyroid sufferers whose conditions were previously considered “subclinical.”

How to Treat Thyroid Issues Naturally

Why are so many people’s thyroids under siege? It all depends on whom you ask. A nutritionist might blame our unhealthy addiction to processed foods, while an environmental scientist will cite research that links toxins in the water supply to weakened immune systems. Still others will caution that our overly stressed lifestyles and lack of sleep are throwing our thyroids off kilter.

Regardless of the reasons, all experts agree that the best way to treat a thyroid problem is to prevent it from developing in the first place. Diet is a good place to start.

“Iodine is the most important mineral for production of thyroid hormone.”

The first thing to look for: iodine deficiency. “Iodine is the most important mineral for production of thyroid hormone,” Thompson explains, “and many people don’t get enough of it.”

In 1924, U.S. salt companies iodized salt in an effort to eliminate iodine deficiencies. Today iodizing salt is mandatory in 120 countries but is voluntary in the United States. While ordinary table salts still contain iodine, kosher salt and some gourmet sea salts do not. Nor do the majority of salts that end up in processed or fast foods.

Over the past 20 years, the percentage of Americans with low iodine levels has quadrupled. In a National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that more than one in 10 Americans are deficient in iodine.

To boost iodine levels, Thompson suggests you use iodized sea salt for seasoning. She also advises eating more seafood and sea vegetables, such as kelp, nori and wakame (these are featured in sushi, soups and many other Asian dishes and are widely available in health-food stores and larger markets).

Many nutritional experts advise people who suspect or know they have thyroid problems to avoid eating large amounts of cruciferous vegetables, such as broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower and Brussels sprouts, especially when raw. These vegetables can have a depressive effect on thyroid function. (See “Can People With Thyroid Conditions Eat Cruciferous Vegetables?” for more on this topic.)

Another food that may depress the thyroid is soy. While soy can be an important protein source, it is not your thyroid’s favorite food. “In high quantities, soy depresses thyroid function,” says Shomon. Eating soy in moderation is fine, but if you have soymilk for breakfast, a soy smoothie for lunch, a soy burger for dinner and take soy supplements to protect against heart disease or hot flashes, it may be time to cut back.

There is a wide array of nutrients helpful in promoting healthy thyroid function. At the top of Thompson’s list are gamma linoleic acids (GLAs), such as:

- Evening primrose oil and black currant oil, both of which help the thyroid produce hormones.

- The mineral selenium and the amino acid tyrosine help convert the inactive T3 thyroid hormone to the active T4 version. Thompson suggests a selenium supplement or a supplement that combines selenium with iodine and tyrosine.

Because an inflamed or swollen gland often accompanies thyroid problems, it’s also important to include anti-inflammatory foods in your diet, such as the essential fatty acids omega-6 and omega-3.

Finally, water is essential for proper immune-system function, so whenever possible, choose filtered or pure spring water over sodas and other drinks. Sip water throughout the day, not just when you become thirsty (a sign you are already dehydrated).

You can also support your thyroid by minimizing sugar, artificial sweeteners, caffeine, dairy and wheat as well as flavor and color additives, as these foods pose a challenge to many people’s immune systems, says Thompson.

How Chemicals and Toxins Can Affect Thyroid Health

Getting the right food and nutrients is just the start of your thyroid challenge.

Environmental scientists are pointing to a growing body of research that suggests the chemicals in our air, water and food supply may be confusing and taxing our immune systems. According to Paul Connett, professor of chemistry at St. Lawrence University in Canton, N.Y., the fluoride we ingest through tap water, processed foods, toothpaste and mouthwash suppresses thyroid function.

The fluoride we ingest through tap water, processed foods, toothpaste and mouthwash suppresses thyroid function.

“In the 1950s, doctors in Europe treated patients with hyperthyroidism with sodium fluoride tablets,” he explains. “The doses they were using are within the range of what we get in people living in fluoridated communities.” Connett suggests that fluoride may cause problems for those with hypothyroid disorders because it mimics the action of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), the hormone that catalyzes the release of hormones from the thyroid, and desensitizes the protein receptors that receive TSH.

Connett and others believe that people concerned about their thyroid health should not only filter their tap water or drink bottled water, but also avoid fluoridated toothpastes and mouthwashes, as well as processed foods (which may be made with fluoridated water) and fluoride-rich foods such as sardines and cooked spinach. (Connett is among a group of scientists and alternative practitioners who reject the notion that fluoride has dental health benefits; most conventional dentists disagree and continue to support fluoridation.)

How Stress Affects the Thyroid

While the idea of chemical stressors is daunting, emotional and mental stress may be an even bigger concern. Some doctors believe that serious physical or mental stress can trigger the immune system to attack the thyroid, especially if you have a family history of low thyroid, diabetes, or other rheumatic or autoimmune illnesses. But even if you don’t have a family history of autoimmune diseases, it’s still important to make sure that your stress levels aren’t weakening your thyroid or getting in the way of your body’s healing processes.

“There is a tremendous amount of frustration built into our everyday lives,” says Shames, “all of which has a negative impact on our biochemistry. Plus our rapid pace of life leaves little time for immune-restoring activities such as exercise and a solid night’s sleep.”

“When you are going through a difficult time or a chronically stressful situation,” advises Shames, “utilize every good stress-reduction technique available to you. If you don’t know any, get some training and try a few out. You could choose meditation, self-hypnosis, or specific relaxation exercises from biofeedback or yoga.”

Shames also advises his thyroid patients to exercise, to stay connected with friends and, if they need it, to seek out professional counseling. But the basic message is simple: When your body starts breaking down or getting overwhelmed, it’s a clear sign you need to take better care of yourself. Go easy, advises Shames. Back off from overly ambitious plans. “If you’ve been working without a break for months on end, schedule a vacation. Get out of your body’s way and let it heal.”

Treatment for Life

The good news about hypothyroidism and other thyroid diseases is that they are treatable. When lifestyle changes fail to help (and in many cases, before they are tried), most doctors treat thyroid problems with both synthetic and natural prescription hormones.

The standard therapy for hypothyroidism is a synthetic hormone called thyroxine, sold under the brand name Synthroid. An alternative natural product, sold by prescription under the brand name Armour, is made of desiccated animal thyroid gland. It is popular among many alternative and complementary health practitioners because they believe it most closely resembles our body’s own natural thyroid hormone. There is little convincing evidence that one type of product is consistently better or more effective than the other: It just depends on the individual’s condition and body chemistry.

“There is no one best medicine for all low-thyroid sufferers,” says Shames. He explains that finding the right drug and the correct dosage can be a frustrating process of trial and error that can take doctor and patient months or longer to master. Sometimes a combination of two drugs is the optimal solution. Sometimes one drug works well for five years and then is no longer as effective.

There is one generalization that can be made, however: Once you start taking any prescription thyroid medication, you’ll probably have to keep on taking it. Most thyroid medications are designed to supplement or replace naturally occurring thyroid hormones – not to strengthen or “cure” the thyroid gland itself. Over time, thyroid medication effectively shuts down the thyroid gland, causing it to slow or halt production altogether, creating a lifelong dependence on supplemental hormones. This phenomenon has made thyroxine one of the most prescribed drugs in the United States. It’s also a consideration that encourages some hypothyroid patients to investigate alternative treatments, including naturopathic and Chinese medicine, before turning to prescription hormones.

In many cases, particularly when thyroid disorders are caught early enough, alternative and integrative methods prove very effective in rebalancing the body’s chemical and hormonal activity. In other cases, they don’t.

The key, according to Shames, is to listen to your body, respect your instincts and take charge of your health. “You need to be as active about your medical care as you are about going to the gym,” he says.

Shames encourages patients to do their research, weigh their options and come to their appointments prepared to talk openly about their concerns and priorities. “If you don’t feel like you are being listened to,” he insists, “fire your doctor!”

Fortunately, Heidi Raschke didn’t have to take Shames’s advice. After a few months of tinkering with her dosage, she found that Synthroid did the trick. Now an editor at a major metropolitan newspaper and the mother of a toddler, she’s busier than ever and feeling fine.

“It’s a minor issue in my life now,” she says. “Having a thyroid condition is awful when it’s not being properly treated. But for me, the medication was a miracle. It made me feel like myself again.”

What Are the Symptoms of Low Thyroid Function? A Self-Test

The symptoms below may indicate low thyroid function. If you experience any combination of these, you should talk to your doctor about getting a thyroid function test.

Do you …

- have unusual fatigue unrelated to exertion?

- feel cold constantly?

- have feelings of anxiety that sometimes lead to panic?

- have trouble with weight, often eating lightly, yet still not losing a pound?

- experience aches and pains in your muscles and joints unrelated to trauma or exercise?

- feel mentally sluggish, unfocused, or unusually forgetful?

- know of anyone in your family who has ever had a thyroid problem (even you at an earlier age)?

- suffer from dry skin, or are you prone to adult acne or eczema?

- go through periods of depression, and/or lowered sex drive, seemingly out of proportion to life events?

- have diabetes, anemia, rheumatoid arthritis, or early graying hair? Does anyone in your family?

- experience significant menopausal symptoms, including migraine headaches, which other therapies do not relieve?

Reprinted with permission from Thyroid Power: 10 Steps to Total Healthby Richard L. Shames, MD, and Karilee Halo Shames, RN, PhD. For more information, visit www.thyroidpower.com.

Be Kind To Your Thyroid

- Stop smoking. Smoking increases your risk of developing thyroid problems.

- Avoid fluoride. Fluoride depresses thyroid function.

- Go easy on soy and cabbage-family vegetables. They inhibit thyroid hormone function.

- Be careful about radiation. Avoid direct radiation to your neck. Make sure your dentist uses a thyroid shield when taking X-rays.

- Green up your cleaning supplies. Replace your “extra strength” cleansers with less toxic options. Because chlorine suppresses thyroid function, minimize cleansers with bleach and heavy-duty chemicals.

- Increase your iodine intake. Sushi and iodized salt are two good sources.

- Reduce stress. Exercise, sleep and reaching out to others can help ease stress. Build relaxation into your schedule.

The Numbers Game: How to Get an Accurate Thyroid Diagnosis

The consequences of a thyroid misdiagnosis can be huge, because the longer thyroid disease remains untreated, the more the metabolism gets out of whack. That means a person will not only be more depressed, more tired and gain more weight, he or she will also be increasingly susceptible to the severe effects of thyroid disease, such as heart disease and difficulties conceiving and bearing children.

Unfortunately, test results aren’t always clear. “When you have a thyroid situation, testing isn’t black and white,” says Richard Shames. “If you have a lot of symptoms, even if you test in midrange, you need to be suspicious.”

Here are a few suggestions to help you get the right diagnosis on the first try.

1. GET TESTED REGULARLY: The American Thyroid Association recommends that women over 35 get their thyroids tested every five years, and that people with a family history of thyroid disease or other autoimmune diseases get checked more regularly. A thyroid test should also be part of your prenatal plan. Not only can thyroid disease make it difficult to get pregnant, an undiagnosed thyroid problem in the mother can have severe consequences for a baby, including low birth weight, low IQ and stillbirth.

2. BE SPECIFIC ABOUT YOUR SYMPTOMS: “It’s more common for a hypothyroid person to go to a doctor and leave with a prescription for Prozac than with a thyroid treatment,” says Mary Shomon, who places part of the blame for improper treatment on the bureaucracies of managed healthcare. “It costs added money to order a blood test,” she says. “But it costs nothing to write a prescription for an antidepressant.”

Shomon also thinks that the communication style between patient and doctor is partly to blame. “Doctors don’t understand concepts like ‘I feel fat’ and ‘I feel tired’ because they don’t translate into actual symptoms.” What patients need to do, in Shomon’s view, is to quantify, quantify, quantify. “Instead of saying ‘I’m always sleepy,’ tell your doctor that you used to sleep eight hours a night and have energy throughout the day. Then explain that you now sleep 11 hours a night and feel like you are walking around half dead,” she says. “Give specific numbers for the calories you eat, the hours per week you exercise, the pounds you have gained in the last month or year.” (For more ideas on how to successfully work with your doctor, see the “Empowered Patient.”)

3. KNOW YOUR NUMBERS: The most common way that physicians diagnose hypothyroidism is with a blood test that measures thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), the messenger chemical that instructs the thyroid gland to produce the T4 thyroid hormone. Both the Shameses and Mary Shomon say that relying on a blood test alone is problematic. Not only can the results be misinterpreted, but blood tests often miss borderline low-thyroid sufferers who could be helped if properly diagnosed. Until recently, physicians accepted the normal TSH range of 0.5 to 5.0 mIU/L. But new clinical guidelines published in late 2002 by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) call for the “normal” range to be between 0.3 and 3.04. AACE anticipates that the new guidelines will result in millions of new hypothyroid diagnoses.

This originally appeared at “Little Gland, Big Problems” in the April 2004 issue of Experience Life.

This Post Has 2 Comments

I think I need to change my eating and sleeping habits. I ate so much processed foods and lack of sleep. Thank you for sharing these information.

Several years ago, at age 43, I was experiencing an unusual increase in fatigue that had me crawling into bed for the night at 8pm. I knew something was wrong when my Mom, who had Stage 4 cancer, had more energy than I did. My functional-medicine doctor ordered a blood test to check my reverse T3 level which is not usually checked by most primary-care doctors — they check T3, T4 and TSH only. It turned out my reverse T3 levels were really high, indicating that my body wasn’t converting T3 to an active form for my body to use. Essentially, I was hitting the gas pedal, but the car wasn’t going anywhere. This made me clinically hypothyroid and now I take a supplement to give my body the active form of T3 needed to function.