I write this to you between bouts of pounding on a fish tank in a bizarre form of CPR designed to bring a minnow back to life. It works. The minnow has been swimming like a drunken maniac all day, then floating to the top of the tank. I knock on the tank, and the fish springs back to life and swims around for an hour or two . . . before dying again. I don’t want to bury this minnow because there will be tears (not mine) and feelings of failure (mine).

The tears will come from my kids. We’ve lost several minnows, which are interred under stones in the backyard. (I’ll say this for burying a minnow: It’s not a lot of digging.)

Ordinarily, I prefer my fish dead. In the past month, I’ve dined on Alaskan salmon, cod, and halibut, all wild caught. I’m acutely aware that our oceans are being fished to extinction, so I eat only fish I know are being managed well enough that there’s no chance I’m eating the exact one that will be the tipping point.

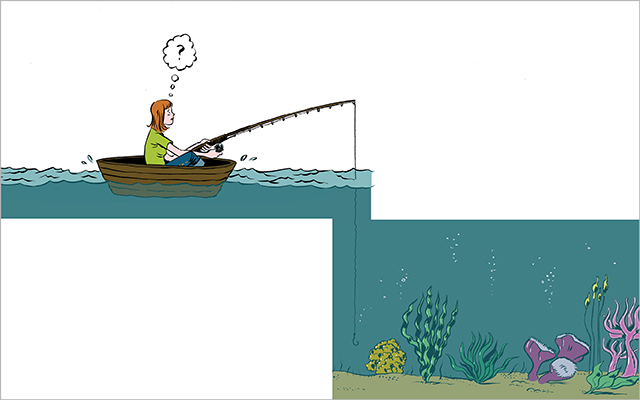

My minnow came to me as part of an effort to understand fish, the oceans, and our part in the food cycle.

It all started a year ago with stories I wrote on the future of fish. The articles examined a coming world in which closed-containment fish farms take pressure off our oceans. These aquaponic farms allow fish to be raised in warehouses, far from any sea (where domestic genetics or diseases cannot be transmitted to wild fish), with the water cleaned by plants, often basil or lettuce (which are another food source for people), or algae. Interviewing aquaculture pioneers, I became convinced that raising fish in buildings will be a key to having a functioning planet with 9 billion people on it.

When my stories ran, the good people at Back to the Roots reached out to me: The Oakland, Calif., makers of home farming kits have an aquafarm they developed for homes and classrooms. It has little pots for herbs on top and a tank for fish below. Would I like to try it, they asked.

My response: Boy, would I.

What followed was a year discovering that sustaining a closed-containment system for fish is really hard. A lot of minnows perished, and dozens more plants never grew.

And I found out that snails are hilarious. They squiggle to the top of the tank, then cowabunga! They jump off and bobble to the bottom again. My kids will pause during dinner to yell, “Snail jumping!” And we all look and laugh. If our minnow dies, we might just become a strange family with snails for pets.

Ultimately, I have come away from this semi-failed, semi-successful experiment with a much deeper respect for nature. Do you know how many organisms it takes to keep an ocean going? Untold billions. They’re needed to absorb every dead slug, fallen kelp strand, and raindrop — and then transform them into a zero-waste circle. Who are all these microbes, plankton, and animals? We haven’t even named them all. How do they interact? We barely know.

When you spend a year trying to make an ecosystem the size of a puddle work, and you can’t, it really brings home the point that the functioning of every roadside wetland is a heck of a lot more complex than it looks. Recently, the World Bank estimated that if we had to account for the value of natural resources like microbes that clean things and the water that they clean, it would total more than $40 trillion.

Do I recommend that everyone get an aquaponic home fish tank? No, not if what you want is fresh basil. There are far better ways to meet that need. And no, not if you want a pet. Hilarious as snails are, they lack personality, as far as I can tell.

But if you want to understand the fragility, the incredible majesty of the world that creates billions of organisms, many of them fish relying on incalculable millions of other organisms, this is a heck of a hobby for the winter.

This Post Has 0 Comments