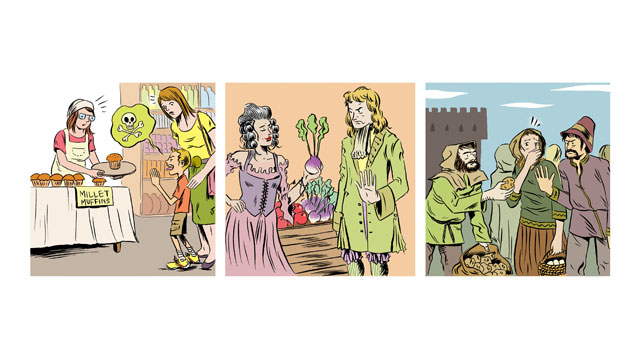

My 5-year-old and I were in the grocery store a few weeks ago, and a nice lady in a prettily embroidered apron was giving out samples of millet-flour muffins. My son actually eats millet — they make it as porridge every Wednesday in his preschool class for a morning snack — so I was hopeful. I told him what the muffin was made of, and offered him a little bite. He gingerly tried a piece about the size of two motes of dust.

“How is it?” I asked chirpily, fingering a package and trying a bite of millet muffin myself. (For the record, I thought it tasted sort of gummy and overly healthy.) My son didn’t answer me. “What did it taste like to you?” I asked.

“Like . . . .” my son trailed off, looking abstractly into the middle distance, as if the word was on the tip of his tongue. “It tastes like . . . .” He trailed off again.

“It tastes like millet porridge at school?” I asked.

“No,” he said. “It’s, like, ah.” The nice lady in the pretty apron leaned in to hear, too. “Poison,” he concluded, nodding with satisfaction, having retrieved the exact word he sought. “Poison.”

It was one of those moments in which apologies seem really inadequate.

Happily, however, I’m a student of food history and can take solace in the fact that human beings have something of a spotty reputation embracing new foods.

Almost everyone knows the famous quote from Jonathan Swift: “It was a brave man who first ate an oyster.” But given the anxiety all unfamiliar foods tend to trigger, it was probably a brave man who ate the first anything.

There’s this funny little British book I own called Spade, Skirret and Parsnip: The Curious History of Vegetables, by Bill Laws (The History Press, 2006), that details some of the hysteria provoked when people have had new vegetables introduced to them. Allow me to share a few of my favorites.

Potato Panic

Laws notes some of the very first cultivated vegetables were most likely peas, beans, onions, lettuces and cabbages, and they were first harvested before written history, so we have no record of the first person to eat a pea, or whether their preschoolers thought they tasted like poison. Yet, there’s much in the written record on what Europeans thought about potatoes, which were introduced to the continent after being “discovered” in South America.

In England, Ireland and Scotland, the potato quickly took up a key role in the wars between Roman Catholics, Protestants and those suspected of witchcraft. What do potatoes have to do with witchcraft? In order to grow potatoes, you plant mini spuds, called seed potatoes, which then grow into the bigger potatoes we consume. Some saw this magical amplification as hocus pocus — as if potato farmers were on par with reanimating the dead. And some took it as proof of Christ’s Resurrection, so much so that the potato became a Protestant political slogan in 1765: “No potatoes. No popery.”

Meanwhile, in the rest of Continental Europe, rulers wanted their peasants to eat potatoes because the vegetable promised to end food shortages, and thus prevent riots and unrest. But alas, no one would try the innocuous vegetable. In Prussia, writes Laws, citizens were persuaded to eat potatoes only after a famine, and, more pointedly, after Frederick the Great’s armed soldiers convinced them to do so.

A British gardener touring Russia observed the uncomfortable introduction of the root vegetable that went on to be the root of the best vodka: “Many of the peasants refuse to eat or cultivate this root, from mere prejudice, and from an idea very natural to a people in a state of slavery, that any thing proposed by their lords must be for the lord’s advantage, and not theirs.”

In France, a man named Antoine-Augustin Parmentier tried every which way he could think of to get the French to eat potatoes. And he went about it in a very French manner, first persuading Marie Antoinette to wear potato blossoms in her hair, and then by offering multicourse dinners in the French court featuring potatoes.

When that didn’t do the trick, Parmentier planted a field of potatoes protected by showy guards during the day, and left it unattended at night, knowing full well this would entice theft. Sure enough, the fields were raided at night, the potatoes passed around as contraband that the rich wanted to keep away from the poor, and that’s more or less how French fries were born.

Eggplant Anxiety

Eggplants came to Northern Europe after being introduced through the Spanish Moors, and the fruit brought a whole lot of fear with them. At first it was thought any Christian who tasted an eggplant would die instantaneously (though, it was believed, Muslims would not meet their demise from the plant’s purple berry). Many Europeans also thought eating an eggplant would produce madness (a reputation due, in part, to eggplants’ membership in the nightshade family, which includes some poisonous plants). This led to the eggplant’s nickname, “mad apple.”

Once European scholars started evaluating eggplants, writes Laws, they really let those large purple vegetables have it, and blamed them for “a succession of ailments from piles, halitosis and liver obstructions to a poor complexion and, ultimately, leprosy.” It was enough to make anyone nervous around the baba ganoush.

Tomato Terror

Tomatoes were brought to Europe by Spanish conquistadors returning from Central and South America, and the red globes were initially regarded with extreme suspicion. People questioned the tomato’s “slimy juice” and immediately assigned the current star of pizza and pasta various sexual qualities, declaring that it was an aphrodisiac and caused promiscuity. Some insisted that it was poisonous.

In Germany, some thought tomatoes were probably used by witches to make werewolves (thus, for a while, tomatoes were dubbed “wolf peaches”).

These anti-tomato feelings lasted for hundreds of years, though by the late 1800s, when tomatoes were commonly eaten, there were various legends about public figures eating tomatoes before crowds to prove to their constituents that they would not drop dead upon consuming the ruby fruit.

It’s amusing now to consider that ketchup, a condiment so commonplace it’s served up in packets, was once perceived as a scary potion that would provoke sexual madness, sickness or both. And ketchup on French fries — it’s like Godzilla teaming up with King Kong in an attack of vegetable fear!

Salad Scare

Human resistance to new vegetables was not solely restricted to potatoes, eggplant and tomatoes. Oh, no. Most edibles were regarded with fear at some point during history.

Cucumbers were thought to cause dysentery and malaria. People were warned off radishes because they bred “scurvy humours and corrupted the blood.” Turnips were to be avoided

because they caused “carnal lust.” Turnips! Those witchy seducers!

For me, the takeaway here is that to fear new foods is an all-too-human trait, and that for all our diverse cuisines to evolve, it meant that someone, at some time, had to be willing to eat outside of his or her comfort zone.

Does this mean I’ll get my kid to enjoy a millet muffin anytime soon? Maybe not. But if I regale him with these anecdotes, someday he just might try a turnip. And if he won’t, I’ll just plant a field of them and surround it with showy French guards during the day.

3 “Weird” Foods Worth a Try

Many nutrient-dense superfoods are relatively unfamiliar to most U.S. consumers. But they are increasingly popular in healthy-eating circles. The perks of these three treats deserve special note:

- Chia seeds. In pre-Columbian times, chia seeds helped sustain Aztec warriors during times of battle. Full of fiber and omega-3 fatty acids, nutty-flavored chia (available whole or ground) makes a great hunger-sating snack. Add it to cereal, yogurt or smoothies.

- Watercress. The fast-growing leafy green is finding overdue popularity for its high calcium, iron, and vitamins A and C content. Add to salads, soups or sandwiches for a peppery crunch.

- Açai. Studies of this Amazonian berry are still under way. It has been proven, however, to be exceptionally rich in antioxidants, especially anthocyanins, which are linked to cancer protection. Açai juices and smoothies are favorite recovery snacks among athletes.

This Post Has 0 Comments