I Know I Should Exercise But . . .

With Diana Hill, PhD

Season 11, Episode 11 | September 2, 2025

Nearly all of us encounter mental barriers to moving our bodies. Perhaps it’s, I’m great at starting exercise programs but I never stick with them. Or maybe it’s, I have no time or energy left for exercise, or I keep comparing myself to people in an exercise class.

Whether one of these — or some variation of them — rings true for you or not, there are strategies for overcoming the obstacles. In this episode, Diana Hill, PhD, shares the reasons we often don’t move and provides us with valuable tools for moving past what’s holding us back so we can get the physical activity we know is so good for us.

Diana Hill, PhD, is a modern psychologist, international trainer, and expert on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), redefining what it means to live with vitality. As a leader in psychological flexibility, she empowers individuals to reclaim and focus their energy in meaningful, sustainable ways. Drawing from the most current psychological research and contemplative practices, Diana bridges science with real-life application to help people create lives that they love.

She is the author of several books, including Wise Effort: How to Focus Your Genius Energy Where it Matters Most, The Self-Compassion Daily Journal, and ACT Daily Journal. She cowrote her latest book, I Know I Should Exercise But . . . with Katy Bowman, MS, biomechanist, and founder of Nutritious Movement.

Hill’s insights have been featured on NPR and in the Wall Street Journal, Mindful Magazine, Woman’s World, Real Simple, and Psychology Today, among others. She is the host of the Wise Effort podcast.

In this episode, Hill shares important insights around the mental blocks that can prevent us from moving our bodies and what we can do to move past them, including the following:

- While each of us could come up with our own unique reason for not exercising, there’s often a familiarity between them, including things like exercise being uncomfortable, something you don’t have time for, or something your environment doesn’t support.

- Psychological flexibility, according to Hill, is probably the most important skill you can have to be able to make and sustain a change in your life. It’s your ability to be faced with obstacles, connect to your values, and continue to pursue what’s important to you.

- Your values are intrinsic motivators, which are distinct from extrinsic motivators. Extrinsic motivators can be helpful to some degree, but they are not sustainable long-term. They can even be demotivating if we don’t see the results we’re hoping for.

- Acceptance is a key process that allows us to change. Unless we can practice acceptance of discomfort, it’s really hard for us to change a behavior. This is because changing behavior is uncomfortable.

- The “righting reflex” refers to trying to set someone “right” — or trying to tell them all the reasons they “should” do something. It’s more effective to help people uncover their own reasons or motivations for wanting to move, says Hill.

- It’s helpful to notice and separate yourself from negative thoughts rather than trying to change or suppress them.

- Choosing compassionate thoughts — or focusing on kind and supportive self-talk — can boost motivation and resilience.

- “Urge surfing” is a strategy Hill explains as noticing when you have an urge rising in you and — just like a surfer would do on a wave — you stay on the board and ride it out. You don’t jump off or give into the urge.

- Behavioral stretching is a technique that Hill encourages that involves doing something that’s outside of our comfort zone on a regular basis. This can help improve mood and well-being, she says.

- How to Stop Talking Yourself Out of Exercise

- How to Create a Diverse Movement Diet With Katy Bowman, MS

- The Way of the Healthy Deviant

- I Know I Should Exercise But . . . 44 Reasons We Don’t Move and How to Get Over Them by Diana Hill, PhD, and Katy Bowman, MS

- DrDianaHill.com

- NutritiousMovement.com

- @drdianahill on Instagram

- @nutritiousmovement on Instagram

ADVERTISEMENT

More Like This

How to Stop Talking Yourself Out of Exercising

Psychologist Diana Hill and biomechanist Katy Bowman, coauthors of a new book, share tips on how to clear the mental hurdles that keep you from moving your body.

How to Create a Diverse Movement Diet

Learn about Bowman’s concept of the “Movement Diet” and how anyone can improve the health of their movement plan by being thoughtful about “movement calories,” “movement macronutrients,” and “movement micronutrients.”

The Way of the Healthy Deviant

A rulebreaker’s guide to becoming a healthy person in an unhealthy world.

Transcript: I Know I Should Exercise But . . .

Season 11, Episode 11 | September 2, 2025

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Welcome to another episode of Life Time Talks. I’m David Freeman.

And I’m Jamie Martin.

In today’s topic, we’re going to be talking about I know I should exercise, but. Nearly all of us encounter mental blocks to moving our bodies, some of them you might have heard of. I’m great at starting exercise programs, but I never stick with them. What have you heard? Maybe what?

I have no time or energy left for exercise.

I keep comparing myself to people in exercise classes.

My partner hates to move. I can’t get them on board to move with me.

So perhaps one of these rings true for you, or maybe there’s other reasons that popped in your head. We want to get our listeners up and moving, so we know what’s good for them. That’s what our guest for today is going to help us learn and change the way they think about exercises and how we can get our bodies up and moving. We got a special guest. Who do we have, Jamie?

Yes. So we’re really excited. We have Diana Hill with us today. Diana is a modern psychologist, international trainer, and an expert on acceptance and commitment therapy, or ACT, and redefining what it means to live with vitality. As a leader in psychological flexibility, she empowers individuals to reclaim and focus their energy in meaningful, sustainable ways.

Drawing from the most current psychological research and contemplative practices, Diana bridges science with real life application to help people create lives that they love. And Diana, welcome to the podcast. We’re so excited to have you here.

Thank you. I’m so grateful to be here.

So Diana, we’re really excited to talk to you about the book that you’ve recently co-written with Katie Bowman: I Know I Should Exercise, But . . . 44 Reasons We Don’t Move and How to Get Over Them. You know, Katie couldn’t be here with us today, but we also want to share a little bit about Katie because you two are kind of a yin and yang together, helping each other as you created this book together.

Katie is a biomechanist, author, and founder of Nutrition Movement. She’s written many books on the importance of a diverse movement diet, including move your DNA, rethink your position, my perfect movement plan, and the latest, I know I should exercise, but. Katie has joined us on the podcast before, and we’re so excited to be talking about your work together and how this is helping people. Because I know there’s a lot of people who helped provide input for some of the things that you addressed in the book.

Yeah, absolutely. And the title, I Know I Should Exercise, But . . . is a statement that we’ve heard so many times, we’ve said so many times, and then we have all the reasons after. Everyone can come up with their unique reason.

Yes.

But there’s a flavor, a familiarity to these reasons, which have to do with things like it’s uncomfortable. And I don’t want to. And I don’t have enough time. And my environment really doesn’t support it. I’ve got three kids, and a job, and no sidewalks.

So we really wanted to tackle some of these reasons from this unique perspective of me as a psychologist. And I can get to all the psychological factors and unwind those. And then Katie is a biomechanist. She can actually give you the creative out of the box solutions to get moving your body, even with all these reasons on board.

Yeah.

And even within the dedication, the book reads, for everyone who has struggled with moving their body in a way that felt joyful and free. When you like unpack that, can you share what that is for the intended audience, for the message for this book and how we can help bring that to life?

Yeah. I mean, we can all think about ways in which we’ve struggled with moving our body that is not joyful and free, whether you’re moving your body because it’s a should. We purposely use the word should in the title because exercise has become a should. As opposed to if you remember when you were 3, 4, 5, 6, it was a want. Mom, let me out. I want to go play. I want to go climb a tree. We’re trying to get our kids down from climbing things.

But by the time we’re 45, 55, 65, it’s like, oh, it’s a should. So maybe that’s not joyful anymore. Maybe it’s not joyful for you anymore because it’s become so difficult to make happen in your life, and it feels like another to do. It feels like a task. It feels like a drain.

Or maybe it’s not in a way that’s joyful and free because you haven’t found community, you haven’t found fun. You haven’t found the deeper reasons, the values that would really help you want to move, feel pulled to move, feel inspired by movement, which is really what our hope is for folks.

And to build the book, you did crowdsource ideas from people on this. How did talking to people in your audiences already helped to identify what to cover and all of those different pieces within it? How did that inform the book?

Yeah. So what we did is we just sent out this blanket question of what makes it difficult for you to move your body? Why are the reasons why you don’t move? And people sent in hundreds of different reasons. And then we went through them all, and we sorted them. And what we found in our sorting, which matches some of the science of reasons why people don’t move.

But there was things that had to do with time. Certainly, people say they don’t have enough time. That was a major reason. And then within that, there’s all these really specific things about time. There was reasons that had to do with embarrassment and shame, body image, maybe not knowing the moves. You’re going to an exercise class for the first time, and you don’t know what to do. You don’t know how to put the weights on the barbell, whatever it is.

There are things that had to do with actually our environment making it difficult to move. And there also had things to do with sort of the, more of like the emotional factors that have to do with mood, like it’s uncomfortable, either physically uncomfortable but also emotionally uncomfortable.

So we sorted them into these categories. And then within each of them, we used the actual real life reason that someone wrote in about. And it’s their actual reason. It’s a real reason from a real person, and I address it from a psychological perspective. I give you my best intervention possible. If you are sitting across from me in my office, this is how we’d work through it together. It’s very hands on, very action-oriented. And then Katie gives some ideas around what she would do with someone in terms of creative ways to tackle that barrier.

Katie has been an expert in experience life many times. And what I have always loved is like she is always providing these unexpected ways to move. Or just like this, like even the little things sit on the floor instead of your couch and stretch. She offers very accessible ways of doing this, which I absolutely love. And so I appreciate, and I’m excited to delve into — we’ll get into more of these examples, and you can speak to all of those when we get going.

But you mentioned a few of the cognitive and emotional barriers that people face. Can you share like which of the reasons or blocks in the book is one that you relate to most or that you have dealt with personally?

Yeah. I actually put one of my reasons in there. Because one of my difficulty with movement actually doesn’t have as much to do with not moving. It had to do with compulsive exercise. So I have a history of disordered eating, and compulsive exercise is actually what drove me to want to become a psychologist. And one of my early research was in I was a director of a treatment center for eating disorders for a while.

But my reason was like when I get into exercise, I get so rigid about it, so rule-oriented. It has to be a certain way. I have to be on the machine for this many minutes. It used to be I have to burn this many calories. Where it almost became like this like rule-governed punishment, that it was related to how I ate. It was related to a should, or that I’m bad in some way if I don’t exercise.

And it really influenced my joy and love of movement to the point where there’s periods where I was afraid to go back. And at the same time, movement and exercise is such a key part of my mental health. I mean, as a psychologist, I’m prescribing it to my clients. Like this is part of our mental health plan, is to move your body with others alone. It’s part of my downtime. It’s part of the creative outlet that I can just do this kind of mind wandering creativity when I’m moving. And so I had to reclaim it and learn how to have movement back in my life, but not have it be so rule-driven, and so rigid, and so restrictive.

That makes sense.

Yeah. So Diana, psychological flexibility. For our listeners, I want you to define that. And also kind of share with us the connection between that and movement and exercise. So break down what psychological flexibility means.

Well, psychological flexibility is probably the most important skill that you can have to be able to make a change and sustain a change in your life, whether it’s in your relationship, or it’s at work, or it’s with movement. And to my knowledge, this is really the first book that looks at psychological flexibility in relationship to exercise and movement.

And what it is it’s your ability to be able to be faced with obstacles, like difficult thoughts, difficult feelings, low motivation, and connect to your values, what matters to you, what’s important to you, and continue to pursue what’s important to you, even in the face of those obstacles.

There’s been over 1,000 randomized controlled trials to this point of this, about psychological flexibility. It’s part of something called ACT. And what they found is that it really is the key factor in maintaining and promoting change when people — whether it’s health behavior change, or it’s a relationship behavior change, or a work change. But it’s key to mental health but key also to your ability to adapt to life.

That makes sense. Well, and I just, I think so often of David is working with clients in our clubs all the time, and you talk about — what you’re getting to is like connecting to the values and the why for each person it feels like. And I know, David, that’s important for you as you’re working with clients too.

100%. And at the end of each session, what we end up doing is I give them that golden nugget thought before they go out into the world and just grounding them once again to what they just went through. They went through some hard things. They challenged their body in some difficult ways.

But now, take this gift that you just received and go share it to the world or just now know what you’re capable of doing when you go out there into the world. So it’s so much bigger than just the workout, coming back to the mindset and how you can apply it. So yeah, that’s a big thing for us.

Yeah. You’re also doing something there that’s a key component of psychological flexibility, is that sort of expansive perspective taking. Because what happens in the gym is always just a really nice metaphor for life. So if you can be in a plank and hold the discomfort of a plank and be able to make space for it, allow the discomfort to be there, ride the wave of that discomfort, see it come and go, then maybe you could also be in an uncomfortable conversation with your spouse later and stay there a little bit longer before you bail, before you run out of the room.

So you’re doing plank pose to prepare for spouse pose. And these are some of the real wonderful things about what happens in the gym, is that it’s mental training as much as it’s physical training for life. And then we also get the benefit of values and that what happens in the gym may also help us live out our values in other areas of our life.

I know for myself, when I go to a yoga class, and I come home afterwards, I’m a different mom to my kids than before I left for that yoga class. I’m more present and more patient. I can tolerate more mess and more noise because I’ve done this movement. So we can really live out our values through our movement, and our movement helps us live out our values in our life.

I love that. OK. So we know that the mind tends to naturally amplify the negative. So when we think about the reasons why we can’t exercise, and I’m quoting that, right? Can you talk about how we can use that flexibility to get that separation from those thoughts and how choosing compassionate thoughts could potentially help too?

Yeah. So I really love how you said get some separation from our thoughts. Because oftentimes, our instinct is just to try and change our thoughts or replace a thought with positive thinking. But really, the first step is just to notice that you have thoughts, and you are not your thoughts.

Sometimes, I’ll have clients write like a thought on their hand, like I don’t have enough time maybe on their hand. Or I’m too fat. We could write that on our hand, right? And let’s imagine that. If you were to write I’m too fat on your hand, and then you were to place your hand right up close in front of your face, and that’s all you saw. That’s how you view the world.

Then it’s going to change — Maybe you can’t engage in your yoga class because you’re only thinking about how fat you are. Or maybe you’re thinking only about the size of your legs on the treadmill. But what we do there with thoughts is we can actually move our hand away from our face and get a little bit of space from our thoughts. And then it becomes a thought, but it’s not directing us. We can choose where we place our attention.

So then I’ll sometimes have clients write on the other hand, what if we had a thought that was a compassionate thought? Something that was kind, that was encouraging, that made you feel stronger, that made you feel more motivated? That the thought that you would tell your kid or your best friend if they were having a little bit of apprehension about getting to the gym or going for a walk or moving their body. What would that thought be?

And it may be something like I know this is hard, and I believe in you. You’re courageous. Whatever that thought is. So now we could have two thoughts. We can have one thought that’s not helpful, another thought that’s helpful. And then you are the chooser of which one you pay attention to. Which one are you going to look at?

Because what we know about thoughts from a psychological perspective is that we have no delete button. In fact, when you try and delete a thought, it just comes back stronger. There’s this thought suppression research or the ironic process theory, where people try and not think. Like if you were to right now, try and not think about your big toe. Whatever you do, don’t feel your big toe. Don’t sense your big toe. Get rid of that feeling. Very few people are able to do it. And the only way that they’re able to do it is by doing some kind of mental gymnastics that is like suppressing it, that takes all their energy.

So instead, we want to choose which thoughts we pay attention to, which ones we amplify, which ones we turn to. And the other ones that are not helpful, we step back from, we play with. Maybe we say, thank you, mind, and let them go.

I share a lot of that once again to my athletes, to my family as well. I was just talking about the power of choice, right? The power of choice. And then when you start to break that down, the way you think usually dictates the way you act, and it usually yields the results that you get.

So when you just navigate it as far as you gave the two different options, you still have to make that choice. Or in that morning, when you hear the alarm clock go off, you have the choice to hit snooze and roll back into bed, or you can get up and do it. So that power of choice is definitely huge.

And what I want to now transition to is understanding value-based actions. That’s something that you have spoke on before. When it comes to values, to helping change the behavior, if you can help our listeners understand value-based actions and how values help change behavior.

Well, you were talking about the power of choice and what are we choosing. So what I would really hope is that people are choosing their values. They’re choosing what’s important to them, what matters to them, what is intrinsically motivating to them.

So values are intrinsic motivators, which are different than the extrinsic motivators. So we all know that extrinsic motivators to exercise. Oh, no. I have a doctor’s appointment, and they’re going to take my blood pressure again. Oh, no. I’m going to get on a scale, and is it going to go up or down?

Those can be helpful to some degree sometimes, but they’re not sustainable long term. And one of the issues with those extrinsic motivators is what happens when you have been working out and you’re hitting it, you’re going to the gym, you’re doing all the things, and the scale doesn’t move? Does that mean you should give up? Does that mean you should stop? Does that mean you should feel bad about yourself?

Well, when we bank things on extrinsic motivators, we end up being demotivated when we don’t meet them. So intrinsic motivators are something like values, which are things that have to do with how you show up in the here and now, how you want to be. If someone were videotaping you and they were to play that video, would you feel proud of what they showed you?

If you were to look back on your life 20 years from now and say, that is how I want to use my time. That’s important to me. That set me up for something that I want to be remembered for. Those are your values. And there are things like being kind, being compassionate, being adventurous, being humorous, being playful, being patient.

Everybody’s values are different and unique to them. But when you identify them for yourself, then you can use those values to be the thing that gets you to not press this news in the morning. And you override those thoughts because you remember, oh, there’s something about going to that class. I know my mind is telling me I don’t want to, and it’s loud, and my body is saying it’s tired.

But I also know there’s something, at least for me, when I get up and go to my class a couple days a week, there’s something about going to that class that is how I want to be in this world. Because it’s a deeper reason. For me. It’s social connection. It’s showing up at work afterwards, being able to be more present with my clients. And it’s also my own mental health, that I really value taking care of my mental health. It’s really important to me. Those are things that no matter what, if the scale goes up or down or if I lift heavier or don’t, can be there.

What you’re talking about, and I know this is part — what you’re talking about, the values-based action, it’s really key in the acceptance and commitment therapy that you talked about. And I’d love for you to just explain what ACT is, acceptance and commitment therapy, to our listeners, so they’re very clear about how this all connects.

Yeah. Well, we may have heard of different types of therapy, and every therapy seems to have a different acronym. So there’s like CBT and IFS and MBSR and all these different acronyms. Many of us have heard of cognitive behavioral therapy, CBT, because it’s a very effective therapy. It has a lot of evidence and science behind it.

ACT is the next evolution of CBT. And what’s different about ACT and what I love about ACT is that it has this values component. It has a lot of emphasis on acceptance. So it’s called acceptance and commitment therapy, and those are powerful words, right? But the emphasis on acceptance in ACT is that acceptance is actually a key component, a key process that allows us to change.

This feels really kind of odd, how would acceptance allow us to change. But unless we can practice acceptance of discomfort, then it’s really difficult to change a behavior because changing behavior is uncomfortable, right? Unless we can accept reality as it is, I mean, we’re off in some fantasy land not wanting to look at ourselves or our lives, or we’re in denial about something.

But if we can really practice acceptance, which has to do with willingness and letting go and allowing to be here, then we can actually maybe then take a look, a realistic look, and make that choice that you’re talking about.

So it has an acceptance component, and then it has a commitment component, which is a behavioral component, where there’s a lot of science of we know about behavior change and habit change and how to take really small steps and then reinforce ourselves for those small steps instead of taking big leaps.

So it’s a therapy that’s used in a lot of different places, and the reason why is because it’s really a therapy about human behavior. And so it’s useful for anxiety and depression, but they’re also using it with Olympic athletes. And they’re using it with high performance coaching and lots of different domains now. It’s gotten really quite popular.

Yeah. And staying right there with ACT and how movement professionals, to make sure that they might try to use it, but they might have some common mistakes as far as unintentionally reinforcing movement avoidance. So when a coach is now speaking to an athlete, can you make sure to share with us how to use this correctly to make sure that it’s not used incorrectly?

Sure. Well, there’s a whole methodology to ACT, and it’s hard to describe the whole protocol. It has six different processes in it that you can learn. But some of the pitfalls that I think coaches do that could contribute to avoidance or contribute to entrenchment in really rigid behavior or inflexible thinking.

One is the classic, what they call the righting reflex, which is trying to set someone right, trying to tell them all the reasons why they should do this. And this sort of reason-giving. What we know in psychology is the more that you argue one side, the other person’s going to argue the opposite side. You know this from just being in a relationship, or having a teenager, or having a toddler.

So what we want to do is to help the other person uncover their reasons for why they want to move. And their reasons may be totally different than your reasons for why you want them to move. But if you can elicit what’s called change talk, which is really asking these open ended questions. Things like, well, what would be different in your life if you were exercising regularly? How do you think it would impact some important domains of your life?

So you’ve said your work is really important to you. How do you think it would impact how you feel when you wake up in the morning, and you get in the car, and you go to your first meeting, right? So you want to get an understanding of what’s important to the person in front of you and use that as your lead, asking questions, and get them to tell you why they would benefit from moving instead of you telling them, and then you’re not caught in the writing reflex.

As you said right, I was like, right. OK. Here we go. So let’s talk through some of the shoulds that are in the book, right? And you address it from a psychological flexibility standpoint. Katie offers, again, like you said, some ways to get you moving within that. I’d love to go through a few of these reasons and have you kind of say how you — like give us a preview of what we would find in the book. So I’ll read this first one for you. So exercise feels monotonous and boring, and it’s the last thing I want to do with my free time.

Yeah, well, that feels familiar probably to a lot of people. Yeah. So the angle that we take in the book, one comes from the science of exercise. There’s some really good research from a researcher named Katie Milkman who talks about something called temptation bundling. And what temptation bundling is is you pair something like your exercise with something that you really, really love to do.

So maybe you have a favorite show, or you have a favorite YouTuber that you want to watch. You only watch that YouTuber when you’re at the gym, on the treadmill, or you only listen to your favorite podcast when you’re out on a walk. I do temptation bundling where I call my favorite friends when I’m on a run. And now I’m like on a run, and I get to talk to this person that I really enjoy talking with.

And what they found is that people who temptation bundle, they actually increased their chances of exercising by like 10% to 15%, and they’re more likely to maintain their exercise. So that’s one psychological tool that you could use.

But we also talk about is, OK, so if exercise is monotonous and boring, let’s find some ways to bring some joy to movement. What did you love to do when you were a kid? Or are there ways that you’re moving right now that you love that you could amplify movement around, right?

So for example, I really like to garden. And so I think about ways I can bring more movement to my gardening. And that may be things like digging in the compost. Instead of asking my partner to dig the compost or carry the heavy bag, I can carry the heavy bag. Because I could be preparing for something I’m going to carry that’s heavy at the gym, or I can also carry something heavy in my life. So bringing more movement to things you enjoy and then also bringing more joy to your movement.

OK, awesome. Wanna read the next one?

Yeah. So I don’t have enough time to exercise. I have too much other work to do and have too many other family responsibilities.

One thing that we love to tackle is this either/or type of thinking. And the brain, the mind has a tendency to categorize things because actually, sitting in the paradox of both/and is metabolically expensive. It’s hard to hold both. So our mind wants to choose one or the other.

But really, what we encourage people to do is to shift from this either/or thinking. Can you change that to a both/and? Can you take either I’m exercising or I’m with my family and look for ways to move with your family? How could you make your family time, movement time? And that may be thinking outside of the box. You may actually get a little bit of resistance from the family.

Yep.

Sort of like the resistance of when you wake up in the morning, and you don’t want to, and you remember your values. And oftentimes, when we get over that resistance and we get moving together, then we start to have all the benefits of movement, and it becomes fun and reinforcing. So thinking about things from a both/and perspective is looking at movement as something that becomes part of our life, as opposed to something that is separate from all the other things that we’re doing.

I’m a therapist. I sit for a living. That’s sort of the technical, you’re on the couch, across from another person. And I’ve been really challenged and really inspired by Katie’s nutritious movement to think about both/and ways of doing therapy and moving my body. Sometimes, that’s hey, when we start out our session, and when folks come in, they kind of want to talk about just the day before we get started. We’ll just walk down my lane and walk back.

Some sessions, I’m doing walking, actually saying, let’s schedule a walking session because they are people that are sedentary too, and walking while we do our therapy actually opens up our minds and our perspective. We know we’re more creative when we’re walking. So we’ll do walking sessions.

I also have fit movement into my day, and I will put a yoga class in the middle of my day and then put — if you’re this client, please don’t take this personally. And then put my more challenging client after my yoga class. So I come back. I’m like all zenned out and centered, and I’m here for you, as opposed to the drain that I usually feel around 2 or 3 o’clock in the afternoon.

So we can start to look at it really, really, really differently as opposed to this sort of either/or thinking, as well as the really categorizing our life and having it be a little bit more integrative.

I can share a little bit of a personal experience tied to this one. My daughter, I’m usually a morning workout person, and that’s been great. But I’ve been struggling to find time with my older daughter, who’s getting busier and busier. She’s 14 years old. She’s got — so her like social life is starting to bud, and she’s just got activities.

And she recently asked me if we could start exercising together a couple days a week. And that has been so fun. It’s just this new thing just within the last couple of weeks. But to get that time with her. Just like we’re moving together, but we’re having these conversations at the same time, and it’s so invaluable. It’s like how I feel sometimes about being in the car with them and the conversation, but I get this little extra time and it’s a both/and that’s such a win to get to do both.

That’s awesome.

Yeah. When we can start thinking about ways to move with our kids, because when they’re younger, and they’re doing their sports practices, and all the parents are in the lounge chairs with the cup holders, and the chips, and the umbrella, and they’re like hunkered down for two hours to watch their kid go exhaust themselves on the field.

What if you were walking and stretching and taking a few laps around the field, so that by the time that their thing is done, their game is done, you’ve engaged with it. You’ve moved their body. They’ve moved their body. And now we’re all getting on the car, and we all can go home and hang out.

Because what happens is that we just have these rules and beliefs of like this is what you’re supposed to do. This is what you’re not supposed to do. At the airport, you’re supposed to go and sit down in the chairs while you wait for your gate to go get on a plane for five hours where you’re going to sit.

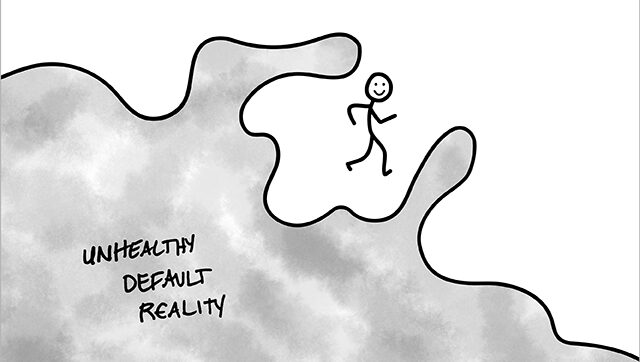

What if while you’re waiting for the gate, you’re stretching? Or you’re doing a few laps around that airport terminal. Yes. You will be a deviant. You will be the person that’s doing the weird thing. But when we look at the health of our country, you kind of have to be a deviant to be healthy. So this is Pilar Gerasimo’s stuff around healthy deviants.

Oh, yeah. So she’s the founding editor of the magazine.

I love her work.

And she’s amazing. Yeah, healthy deviant, all of those things. We actually need to bring her back on too. That’d be good. We should revisit her at some point. Have you been on her podcast or has she been on yours? I think she has, right?

Yeah. She’s been on mine. But yeah. We talk about her in the book and talk about her work in the book. Because that takes psychological flexibility. It takes acceptance of discomfort. It takes out of the box thinking. And it takes connecting to your values. And that really is the definition of psychological flexibility.

Awesome. OK. So the last example we’ll go through and then we’ll jump into a couple other things is, and I like this one because it’s often an intimidation factor. I can’t help but compare myself to other people in my exercise class. I always feel like I am the least coordinated, slowest, weakest of the group. I don’t want to feel that way, so I don’t go.

I think we all can relate to that. It’s really just the human condition, and we all evolved to want to be part of a group. And so we compare to see where we’re standing, and then we pull away if we feel shame about ourselves or embarrassed because there’s that sort of evolutionary risk. If I’m not part of the group, then I’m going to get ousted, and I’m going to die. So it’s an old — a lot of this has to do with our evolutionary psychology.

One of the aspects of psychological flexibility is also attentional flexibility. What are you paying attention to? And we can pay attention to other people and compare ourselves to other people. We could also have attentional flexibility where we’re paying attention to how something feels in our body. We could pay attention to the whole group moving as a whole. It’s kind of fun to watch everybody moving as a whole.

You can also pay attention to your values. You could pay attention to the music. There’s lots of places you can pay attention. When you are only paying attention to comparison, then what will happen is that comparison will grow. So we can practice attentional flexibility. I was actually just — I keep on mentioning yoga because that’s something that I love to do. It’s a movement I love.

But I was in a yoga class this past week, and there was a difficult pose called bird of paradise. It’s this gnarly pose where you put your arms around one leg, and then you stand up on the other leg, and you straighten. It’s been something that I have always thought I never could do. And because I always thought I could never do, but really, it was about if I do it, I’m going to fall over, and people will notice.

And here I am. I’m like in my mid 40s. I’m still worried about people — I still think that people care about what I’m doing or not, as if they’re really paying any attention to me at all. And I finally, this past week, I was like you know what? I’m just going to go for it. I’m just going to go for it. And what I did is I put all my attention into my balance, all my attention into this one leg and really focusing it, grounding it on the floor and feeling my full foot in the floor.

And with all my attention there, I was able to get into, not fully but mostly, into this pose. And I felt so amazing afterwards because I felt so courageous for doing it, for risking the fall. And I also learned a new skill. Wow. If I’m putting all my attention to what everyone else is thinking, I’m not going to have that great of balance. We’re much more balanced when I put my attention into my leg and my foot.

That’s awesome. That’s good for you too. Keep doing it. That skill is going to be there before you know it.

There you go.

All the way into that bird of paradise.

All the way. Or not.

Wherever. As long as —

Chipping away, right. OK. So the book offers a toolkit of psychological tips and strategies that not only help you get the most out of your body for movement but also can be applied to other areas of your life. And I’m going to break down a few of these. We’ll go back and forth here. So can you talk about the first one here, urge surfing.

Oh, urge surfing is such a great skill. It comes from smoking research. And Alan Marlatt was a researcher who looked at what happens to urges? You know, when you have like an urge to do something. And one of the urges that gets in the way of us moving our bodies is the urge to scroll.

So how many times have I heard or have you experienced. You wake up in the morning. You have a plan to get out. But now you’re on your phone, and you’re just scrolling away. Or I even see it at the gym where people are sitting like on the bench where they’re going to lift the weights, but they’re just on their phone for 15 minutes. And they’re like, wow, this — You’re really cutting into the time that you said you didn’t have to exercise.

So urge surfing is noticing you have an urge to do something or an urge is rising in you. And just like a surfer does on a wave, you stay on the board. And you don’t jump off, so you don’t give in to the urge, but you ride it. And what you’ll notice as you pay attention to the sensations and the experience of an urge, is that it grows, and it grows, and it grows, and it grows. And there’s a point where you’re thinking, oh, no, this is going to go on forever. It’s going to kill me.

No one’s ever died of an urge. You’ve never met — I’ve never — I’ve had a lot of clients with urges. No one’s ever died of an urge. People have really done really unhelpful things when they’ve given in to urges. But you watch it rise. And then it eventually will come down again, whether you act on it or not.

The nature of that is it’s a mindfulness skill. It’s an attentional skill. It’s a non-reactivity. It’s building your capacity to be with discomfort at the level of pure sensation. And the more that you do it, the better you get at it, just like surfing. If you jump off early on that urge, the next time that urge comes, you’re going to jump off even earlier, and you will get weaker over time at being able to tolerate urges.

So it is a mental skill to be able to surf an urge. And if you can do it with your phone, then you can do it with maybe you want to emotionally eat, or maybe you have the urge to text someone something that’s really not helpful to text or say something that would be harmful to someone you love. We have all kinds of urges, but we can learn to surf them and ride them out and get better at it.

That’s good. OK. The next one we want to talk about is motivational interviewing. What does that mean? Well, motivational interviewing is probably one of our most effective tools for motivating change in another person. And what’s interesting about that is that we really can’t get other people to change, but we can increase their motivation to change by how we are interacting with them.

It was developed by researchers Stephen Rollnick, and it is used a lot with things like substance use. But how we can use it in coaching is, again, using these more open-ended questions about why someone is going to change.

One of the classic motivational interviewing skills is looking at, like on a scale from 0 to 10, how motivated are you to wake up tomorrow at 7:00 AM and get to the gym? And if someone says I’m like a 3, then you would ask a question, oh, OK, you’re 3. And instead of trying to get them to a 10, you would say something like why are you a 3 and not a 0?

Tell me about that little tiny bit of motivation that’s in there. That little 3, like tell me about it. What is it that’s a 3 that’s not a 0? Because there’s something in there. And then they’ll start to talk about why there are 3. And as soon as they start talking about why they’re 3, well, there’s a part of me that knows that if I go to the gym at 7:00, then I don’t know, I’ll be more productive at work. I’ll feel better about myself at the end of the day. Or someone’s meeting me there that I’m kind of looking forward to meet.

Then you know what things you want to push on and encourage them to highlight and strengthen as their reason, their motivation to change. So motivational interviewing has to do with using questioning that is very client-centered, as opposed to forcing anyone to do anything that they don’t want to do, which always backfires.

All right. Next one, behavior stretching.

Ooh, behavioral stretching. This is a fun one. So behavioral stretching is when you do something that’s outside of your comfort zone on a regular basis. I actually think that we should all behaviorally stretch every day if we can. This would be a good 40-day challenge. Can you do something for 40 days that’s outside of your comfort zone?

And what they found with behavioral stretching is when they actually apply this as an intervention, when they’ve done research on this, told people for two weeks, do something outside of your comfort zone. People’s mood improves. Their well-being improves. Their outlook on life improves. And especially if they start out with a really low mood and they’re feeling really terrible, and especially if they’re behavioral stretching is linked to acts of kindness.

So behavioral stretching may be like an act of kindness. What would that be, a behavioral stretching? It may be something like when I’m at the gym, I’m doing everything kind of exercise-related, right? When I’m at the gym, I’ve seen this guy there like every week. He seems like it could be like a friendly dude.

What if I say, hey, my name is Diana. What’s your name? I noticed you’re at the gym a lot. That would be a behavioral stretch, and I’d be making a connection. And we know about connections is that if you have connections, that you have a sense of community, you’re going to be more likely to go back because you’re going to feel safer there. You’re going to feel more seen. I’m part of something.

And now I know this guy Dave, who’s like at the gym all the time. And I feel a little more connected to him. So that would be an example of behavioral stretching. That is act of kindness and kind outside of our comfort zone.

I like that one.

Like you do see so many people. I mean, obviously, we see this in our health clubs all the time of like they come in with their headphones on. They don’t talk to anybody. They do their own thing. But it would be a really interesting exercise. Like introduce yourself to one new person every week. That’s so interesting. You can create a different community for yourself.

And those weak ties, weak ties are actually some of the fabric of our life. We really learn this during COVID, is that the weak ties, like the communities of who you’re seeing at the gym, actually makes you feel part of something. And we need each other. The lady at the chicken feed store, when I had to evacuate for a fire, she was the person I called who came and fed my chickens for a week. It’s like totally weak tie, but then we don’t realize we’re so dependent on each other.

So when we make those types of connections, and exercise and movement is such a great place for community and building — although they’re called weak ties, they are very much our strong ties. And for our mental health benefits, loneliness is such a big risk factor in terms of our physical health is related to our loneliness. We could do the behavioral stretching to build community and build up those strong ties.

Absolutely. I like that one. All right. Last one we have is strengthening your acceptance muscle.

Yeah. Acceptance. Some people don’t like the word acceptance because it feels like you’re telling me to accept my mother-in-law. That’s not what I’m talking about. With acceptance, it’s maybe we could use other words like willingness is another word, if that fits for you more.

People could try on the word of just allowing or letting be. Staying open to. And when we resist things, there’s the resistance that comes back to us. So I could do a little exercise with us around this now. I want you to, in your head, say no to, and the listeners can do this too. Say no to everything that I’m about to ask you. And notice what it feels like in your body.

Do you want to get up and stretch? Do you want to go for a walk later? Do you want to be open to some of these ideas that we’re talking about on this interview? Notice how that felt in your body. And now, what I want you to do is say yes. And notice the difference. Do you want to get up and stretch? Do you want to go for a walk later? Do you want to stay open to some of the ideas we’re talking about in this interview? You can feel the shutting down versus the opening up.

And so acceptance is just saying yes. It’s not saying yes to things that are harmful to you or yes to your mother-in-law coming for dinner if you don’t want her to come for dinner. But it’s saying yes to the experience of if my mother-in-law is coming to dinner, I’m going to say yes to this because if I am internally saying no and I hate this, I’m the one that’s going to be miserable.

If I’m saying no to the plank pose, I’m going to be the one that’s miserable. Try saying yes while you’re in plank pose and notice how it changes it. Try saying yes when you’re doing your pull up and notice how it changes it. Try saying yes when you’re walking uphill and notice how it changes it. That is the practice of acceptance, and it’s a really, really powerful mental tool that strengthens you, especially when you have that tendency to shy away and close down and shut off.

That’s good.

Yeah, that’s a really — I was just thinking about that in terms of just various ways that I move and sometimes will resist. And I can think of exact movements, the pull-up that you just said. Like that is in my head, but I love the idea of just change the answer, and it’ll change how it feels energetically too. I felt that energetically in my body when you did that.

Yeah.

I go back to that power of choice we were talking about earlier, right?

Yeah.

All right. So Diana, anything that we missed that you want our listeners to have before we get into our mic drop moment?

I guess I just want to say that every listener is going to have their own reason. We’re all individuals. We have context. And I am not setting up the statement that the reason why we’re not moving is because there’s something wrong with you, or you just need to do better mental gymnastics.

We live in a sedentary environment that does not support movement. And for some people, it is much more difficult, and there’s a lot more barriers involved. And so we do have a whole chapter on that. We have a chapter on mental barriers, everything from poor air quality to unsafe environments, to having a lot of financial responsibilities.

And as a psychologist, I have often underplayed that and overplayed that it’s all about you and your mental skills. Our environment is not supporting us. And so we do need to boost our mental skills. We do need to boost our psychological flexibility and our nutritious movement because of the sedentary environments that we live in. So if you’re not moving, it’s not your fault, is what I want to say.

All right, it is mic drop moment time. OK. So how many years have you been in practice?

Oh, probably 15? Yeah. Plus? Maybe almost 20? I don’t know. I’m getting older.

No, no. You’re good. All those years, all those years, accumulated, 15. With that, and now knowing all the knowledge that you have in that space, you now have the 12-year-old Diana sitting on the couch. What do you say to he?

Oh. My 12-year-old Diana was just on the cusp of starting to hate her body, and loving flowers, and loving walking along the creek that was right behind our house. And I will tell her that there’s going to be probably a period of time where you’re going to get messages that there’s something wrong with you, there’s something wrong with your body. And that this love that you have, you have to shed it aside and do it differently.

But you will reclaim it, and you will walk along a creek again, and you will feel embodied. And I really, really, really love you, and care about you, and wish for you to love movement for life.

That’s good. I think we all need that message. Like that’s a really great message to tell to our 12-year-old selves and the 12-year-olds in our lives or whatever ages they’re at. Those good reminders. So Diana, thank you so much for joining us today. We want to make sure that our listeners and viewers can find both you and Katie where you are.

Your website is drdianahill.com. You’re also on social at Dr. Diana Hill. Katie’s website is nutritiousmovement.com, and her social handle is @nutritiousmovement. And of course, they can find your book I Know I Should Exercise But . . . on Amazon and at other bookstores. So thank you for sharing this with us. Thanks for being on and —

Appreciate you.

Yeah. I mean, keep doing this good work. We need more people getting their nutritious movement and that psychological flexibility in their lives.

Thank you. It’s a good joy to be with you.

Thank you.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

We’d Love to Hear From You

Have thoughts you’d like to share or topic ideas for future episodes? Email us at lttalks@lt.life.

The information in this podcast is intended to provide broad understanding and knowledge of healthcare topics. This information is for educational purposes only and should not be considered complete and should not be used in place of advice from your physician or healthcare provider. We recommend you consult your physician or healthcare professional before beginning or altering your personal exercise, diet or supplementation program.