Explore this article:

• The Fundamentals of Strengthening Your Core

• Understanding the Rib Cage, Diaphragm, and Pelvic Floor Connection

• How to Assess Your Core Strength and Balance

• Pregnancy and Your Core

See the moves:

2 Breathing Moves to Strengthen Your Core • 4 Move Core Strengthening Circuit

Despite what fitness proclamations and headlines might lead us to believe, having a strong core is about more than a toned midriff or visible six-pack abs. The core, in fact, is a complex and multilayered system of muscles that wraps your body like a corset, from ribs to hips, belly to back, deeper than the eye can see.

Its job is to create strength and stability for your entire body throughout the day. Strong midbody muscles help you move better, whether you’re running, biking, lifting weights, practicing yoga, or doing routine chores and activities around the house — that is, if those core muscles are well coordinated.

“Your core and all your body parts that attach to it need to work together to make it possible to move better throughout your life,” says biomechanist Katy Bowman, MS, author of Diastasis Recti: The Whole-Body Solution to Abdominal Weakness and Separation.

Visible ab muscles or record-setting plank holds, it turns out, don’t matter all that much: Building core strength is only helpful if you know how to use it.

A strong, well-integrated core will support you when it’s challenged by a movement, and it will make all types of exercises and activities easier and safer. On the other hand, a weak or uncoordinated core — when the muscles just aren’t working together, despite their individual strength — can lead to injury and impeded athletic performance, as well as surprising health issues, including back and joint pain, incontinence, and sexual dysfunction.

A strong, well-integrated core will support you when it’s challenged by a movement, and it will make all types of exercises and activities easier and safer.

“When I see patients with injuries, it’s often traced back to misfires in the core,” says Erika Mundinger, PT, DPT, a physical therapist in Bloomington, Minn.

If the core muscles surrounding your spine are weak, for instance, your vertebrae and discs won’t be properly supported, leading to discomfort and pain. Lower-back problems are the most common sources of recurrent pain and job-related disabilities: 80 percent of adults experience lower-back pain at some point.

The same goes for your extremities. “If you have a weak core that extends to weakness in your glutes, your hips and knees may not be able to support themselves against weight-bearing activities like walking, running, or jumping, and pain can result,” Mundinger says. “If your core is weak and can’t stabilize good posture, it also can’t stabilize your shoulder blades. This can create impingement,” leading to shoulder and elbow pain.

I learned this firsthand over the past decade while practicing fitness pursuits ranging from Pilates to powerlifting (which involves testing maximal strength in the squat, deadlift, and bench press). On the surface, these activities couldn’t look more different: Pilates is the epitome of dancer-like fluidity, while powerlifting is the essence of power and strength.

What I discovered in practicing and coaching both activities are the perils of exercising with an uncoordinated core:

- niggling aches and pains,

- difficulty knowing when and how to breathe during complex movements,

- plateaus or regressions in performance,

- and — at worst — injuries, often involving the lower back and neck from overcompensation.

Perhaps more importantly, I’ve learned the rewards you can reap by combining strength building with straightforward fixes to posture, breathing, and body mechanics: pain that seems to disappear and improvements in performance on the mat, the platform, and everywhere in between.

Success in any physical endeavor depends on a strong and well-coordinated core — one that integrates muscular strength, control, mobility, and breathing from the inside out.

The Fundamentals of Strengthening Your Core

It’s important to get familiar with the muscles that make up the core to understand how they contribute to core coordination.

At the top of the core sits the diaphragm, a dome-shaped sheet of muscle that plays a vital role in the breathing process.

At the bottom lies the pelvic floor, a hammock of three muscle layers stretching from the tailbone to the pubic bone. (This is true for men and women, though the muscles serve different functions based on human anatomy.)

The pelvic floor and diaphragm flank the internal and external obliques and the transverse abdominis, which connect the rib cage and pelvis.

Together, they form what many trainers describe as a three-dimensional “canister” of muscles, bones, and other tissues that wraps around the body from front to back.

While it’s useful to identify the separate parts of the core, it’s important to not focus on training them individually. Because your core works as a whole, it’s only as strong as its weakest element.

Here’s why: Your torso contains a multidimensional system of muscles that generate force or transfer energy while your arms and legs move in three different planes of motion. Though there is often overlap in the three planes, many movements and exercises primarily involve one of the three: the sagittal plane (front-to-back moves, like squatting and deadlifting); frontal plane (moves to the side, like jumping jacks); and the transverse plane (rotation, like golf swings and yoga spinal twists).

When all the parts of the core work together, you can better hold the position of the ribs and pelvis, maintain optimal diaphragm function, and allow the abdominal muscles to do their job.

When all the parts of the core work together, you can better hold the position of the ribs and pelvis, maintain optimal diaphragm function, and allow the abdominal muscles to do their job. Activities like walking, running, exercising, and playing sports become easier, more enjoyable, and less risky for your body.

“You can train more effectively and optimally, and you may even recover faster between training sessions, when the core is strong as a whole,” explains Pat Davidson, PhD, an exercise scientist and strength coach.

Davidson has trained extensively with the Postural Restoration Institute, which specializes in assessing and treating postural asymmetries and movement dysfunctions. The author of the MASS training series, Davidson stresses that while proper breathing and core coordination are important, they do not by themselves address movement quality. Your exercise technique still needs to be on point.

Abdominal muscles that work optimally in conjunction with the breath “are another tool that gives you a chance to be more consistent in your training so you can put in more hours per week, and more days per month,” says Davidson.

“The name of the game with progress is consistency,” he says.

Building your core using a combination of positioning, breathing, and strengthening work will allow you to be more consistent in your exercise, so you can continue to see results — for the long haul.

Understanding the Rib Cage, Diaphragm, and Pelvic Floor Connection

The abdominal muscles are important, but they’re only one component in the complex core structure. Let’s explore three of the other key elements, from top to bottom, and how they work together to create a stable, strong center.

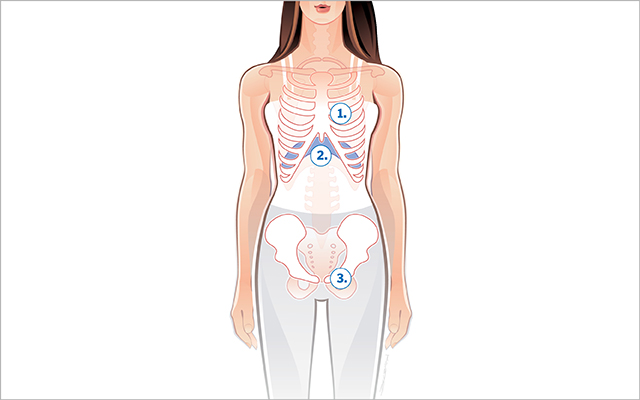

1. Rib Cage

The flexible rib cage can perform a wide variety of movements, the most pertinent being internal rotation, depression, and retraction — moving down, back, and in. (See illustration below.)

The rib cage connects to the thoracic spine as well as the spinal erectors and multifidus in the lower back, and it contains the “deep core” muscles: the internal and external obliques, and the transverse abdominis. These play an important role in keeping your rib cage in a safe position to enable the diaphragm and the pelvic floor to do their jobs.

To picture the rib cage, think of your midsection as the bendy part of a drinking straw. When your ribs are optimally positioned, it’s as though the straw is straight. When they’re not — for instance, if your ribs are flaring out — it’s as though the straw is bent.

To feel what it means to position your ribs so they are drawn in, or “knitted” together, place your thumbs on your lower ribs and middle fingers on the hip bones. Take a deep breath, trying to maintain the distance between your thumbs and middle fingers. In doing so, you will feel your inhale not just in your chest or belly, but expanding around your sides and back — you’re not letting the straw bend when you take that breath.

This ensures that the diaphragm is able to do its job, while also helping the muscles of the pelvic floor maintain their strongest position.

2. Diaphragm

A piston-like muscle, your diaphragm is responsible for your breathing, a function that ensures your survival and also sets the stage for proper movement.

When you exhale, the diaphragm pushes upward and reduces space in your thoracic cavity.

When you inhale, it contracts and flattens, increasing space inside your chest.

“If your diaphragm isn’t optimally positioned over your pelvis, your body will still figure out a way to inhale — because if you cease breathing you will die,” Davidson says. But these suboptimal breathing patterns can cause repercussions elsewhere.

The most common way that the diaphragm moves out of optimal alignment is when we extend, or “flare,” our ribs forward, up, and open, and tip our pelvis forward.

Some people walk like this all day; others flare their ribs when they take a deep breath to brace for an exercise, or press their arms overhead.

Whenever that happens, it compromises the diaphragm’s ability to help us breathe.

The most common muscles we recruit when the diaphragm is out of position are the muscles in the neck and upper back. If we overburden these muscles by calling on them to assist our breathing, they will become fatigued and their primary function will likely suffer, leading to neck, back, and shoulder pain.

3. Pelvic Floor

Many people are surprised the pelvic floor is part of the core. (If you’re not sure where your pelvic-floor muscles are located or how they work, try to stop peeing midstream — they’re the muscles that contract to make that possible.) (See illustration above.)

These muscles are responsible for assisting urinary and fecal continence; supporting pelvic-floor organs, including the bladder and rectum; aiding sexual function; and stabilizing the connecting joints in the ribs, hips, and legs. They also act as a pump for blood and lymphatic circulation.

Pelvic-floor dysfunctions affect one in three women, but are less common in men. Symptoms include incontinence, pelvic pain, and pelvic-organ prolapse, which causes the bladder, vagina, rectum, and other organs to droop painfully out of place.

While these uncomfortable (and often embarrassing) issues are commonly attributed to pelvic-floor weakness, the cause is rarely that straightforward, explains Mundinger.

It’s possible that the muscles are weak or injured, but the dysfunction could stem from misalignments and weakness elsewhere. In that case, strengthening the pelvic-floor muscles will go only so far before the rest of the core will need attention.

The key is coordinated strength of the diaphragm, pelvis, and everything in between.

How to Assess Your Core Strength and Coordination

An uncoordinated core can affect anyone who sits for many hours during the day, those who don’t exercise regularly, those who have suffered a prolonged period of chronic coughing or a medical trauma, or those who have been pregnant. Since your entire core is meant to work together, weakness in one area can lead to an imbalance of this system of muscles. These tools can help you assess your core coordination.

Hollow Test

To test the strength of your core, take a deep breath. As you begin exhaling, draw your bellybutton back toward your spine as far as you can. Hold this position for 10 seconds. If you can’t make it that long, your core coordination may be underdeveloped.

Balance Test

To check your balance, stand on one foot with your eyes closed. Test one leg, then the other. If you can’t hold this position for at least 10 seconds on either leg, an underdeveloped core is the likely culprit.

Posture Check

Assess your natural posture while standing sideways in front of a full-length mirror: If your lower ribs tend to pooch out, or you lock your knees or sway your lower back, your core posture could use a tune-up, says Meredith Butulis, DPT, OCS, a Life Time Academy instructor in St. Paul, Minn. Prolonged sitting is a major culprit here, but carrying your pack or bag on one side of your body, or a poorly arranged work station, can also contribute to rounded shoulders and tight hips.

2 Breathing Drills to Strengthen Your Diaphragm

All the core muscles need to work together, no matter what activity you’re doing. Strengthening your diaphragm through breathing drills, such as these suggested by Mundinger, can help improve your exercise form and aid in better core stabilization.

Complete these two drills, spending three to five minutes on each, twice a week, after your warm-up and before your workout.

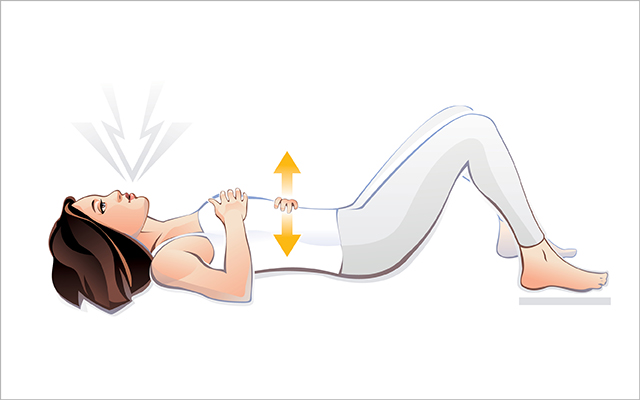

Supine Diaphragmatic Breathing

- Lie on your back with your knees bent and feet flat on the floor.

- Place your right hand on your upper chest and your left hand on your upper belly, just under your sternum.

- Inhale deeply through your nose, drawing the air into your rib cage; your left hand will move upward and your right hand will be still.

- Exhale through your mouth, with pursed lips; your left hand will lower to the starting position.

Body-Weight-Squat Breathing

- Stand in a tall position, with your joints stacked, your ribs drawn down, and your feet at shoulder width.

- Inhale audibly through your nose and down into your rib cage as you squat your butt down between your heels.

- Exhale through pursed lips as you stand back up, drawing your ribs down and bracing your core.

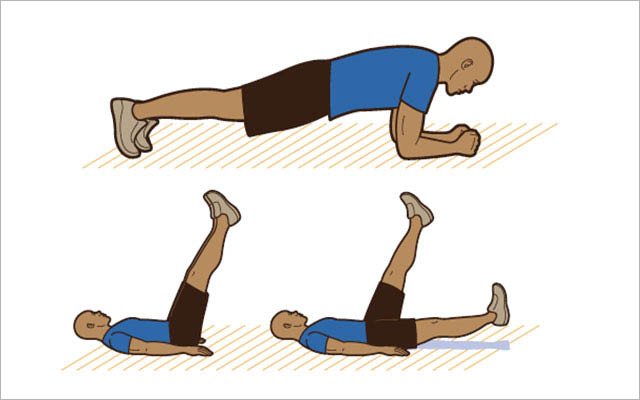

4 Move Core Strengthening Circuit

First and foremost, stand and sit tall — and make it a habit. Drop your lower ribs so they are directly over your pelvis, stacking your joints, one on top of the other, while keeping your ears centered over your hipbones. This makes it difficult to slouch, says Life Time’s Meredith Butulis, DPT, OCS.

She recommends these four core exercises.

- Perform them in a circuit fashion, completing 10 reps on each side before moving on to the next move.

- Complete the circuit three times, twice a week, as a standalone routine or tacked onto the end of your regular workout.

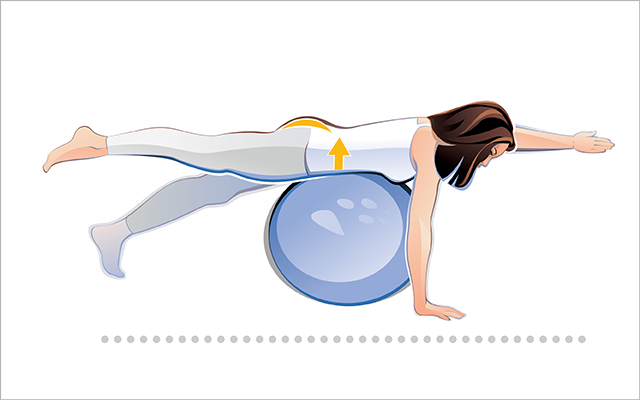

Stability-Ball Bird Dog

- With a stability ball under your belly, position your hands and toes on the floor, as if you were doing a pushup.

- Engage your core by pulling your bellybutton away from the ball and squeezing your glutes.

- Inhale, and slowly lift your left hand off the floor, raising your arm until it’s parallel to the ground, with your palm facing in.

- Exhale, and return your hand to the floor.

- Repeat with your right hand, then right leg, and finally left leg.

Make it harder: Lift your opposite arm and leg at the same time (as pictured); switch sides.

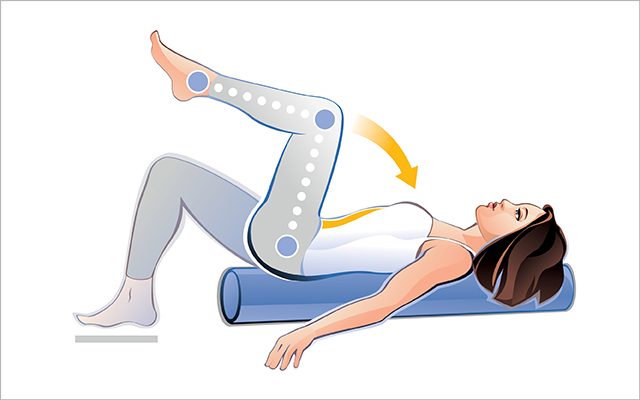

Foam-Roller March

- Lie down on a foam roller that’s long enough to support your entire spine and head; rest your arms on the floor at your sides.

- Bend your knees and place your feet flat on the floor.

- Draw your ribs down and brace your abs as if you’re about to be punched in the belly.

- Keep your core engaged, inhale, and lift one knee at a 90-degree angle toward your chest.

- Exhale and lower your foot to the floor. Repeat on the other side.

Make it harder: Over time, rely less on your arms for support.

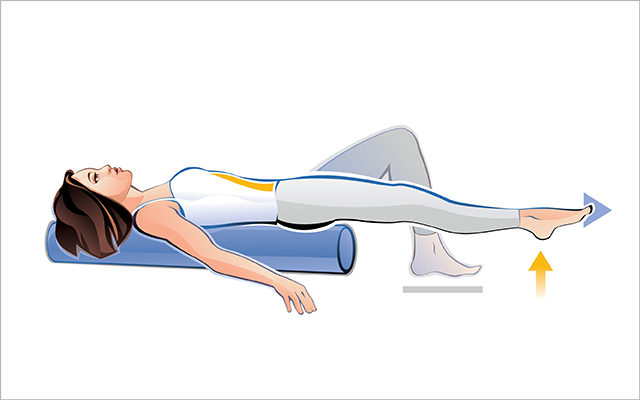

Foam-Roller Leg Extension

- Lie down on a foam roller that’s long enough to support your entire spine and head; rest your arms at your sides and bend your knees, keeping your feet flat on the floor.

- Draw your ribs down and brace your core.

- Inhale, and lift your right foot a few inches off the floor and then extend your leg, reaching your toes toward the wall in front of you.

- Exhale, and return your foot to the floor. Repeat on the left side.

Make it harder: Over time, use your arms less for support.

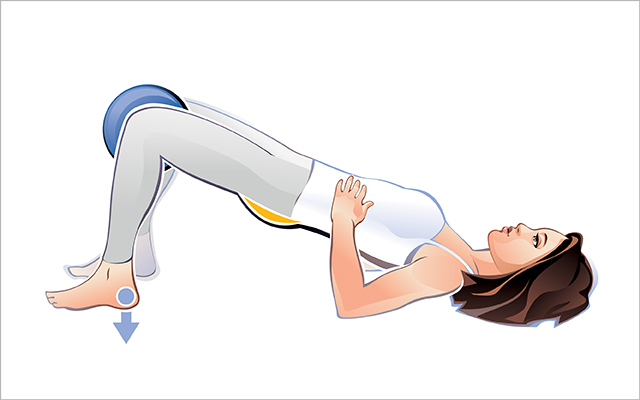

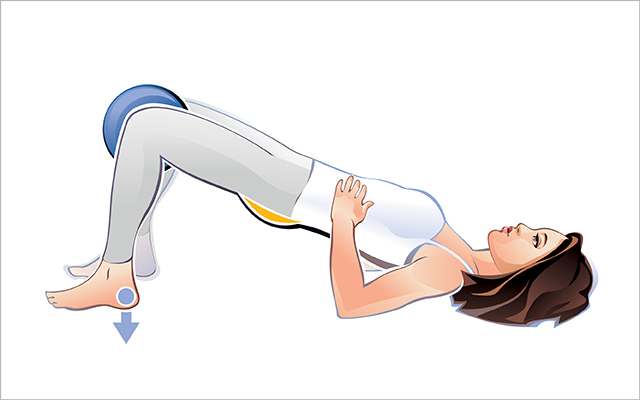

Body-Weight Hip Bridges

- Lie down, with your knees bent and feet flat on the floor and hip width apart.

- Place a ball about the size of a small soccer ball or yoga block between your knees.

- Squeeze your glutes and pull your ribs down toward the floor.

- Inhale and drive down through your heels to lift your hips until they form a straight line with your knees and shoulders. Keep your ribs down.

- Exhale, and lower your hips to the floor under control. Repeat.

(See “BREAK IT DOWN: The Glute Bridge” for more.)

When to See a Healthcare Provider

Core muscles that are weak, misfiring, or not working together raise several red flags that are best addressed by a medical professional. “Treatment plans always include core-training exercises, even for extremity issues,” says Erika Mundinger, PT, DPT.

If you experience any of the symptoms below, see your healthcare provider to obtain a diagnosis and to develop a plan of action — one that may include some of the exercises that follow.

- Lower-back pain

- Joint pain

- Pain during intercourse

- Urination during high-impact exercise or heavy weightlifting (stress urinary incontinence)

- Frequent constipation

- Separation of your abdominal wall, commonly known as diastasis recti

Pregnancy and Your Core

How does being pregnant and giving birth affect core health?

While pregnancy isn’t the time to focus on training your core muscles, you can still take steps to maintain your fitness and keep your midsection strong during your pregnancy. Embracing this approach can help keep your perinatal pelvic floor strong and increase your sense of control during labor. A strong core can also alleviate the pressure that carrying a baby puts on your back and support proper posture to fend off the lower-back pain.

Postnatal, your pelvic floor muscles, the base of your core that supports your bladder, uterus, and rectum, may be lengthened and weakened. A commonly associated symptom of a weakened pelvic floor is stress urinary incontinence (SUI), when physical movement or activity, such as coughing, sneezing, running, or heavy lifting results in slight to moderate urination.

“[Stress urinary incontinence] is not an ‘injury’ per se, but it’s an indication of failure of the deep central stability system, or the core.”

“SUI is not an ‘injury’ per se, but it’s an indication of failure of the deep central stability system, or the core,” explains Julie Wiebe, PT, a Los Angeles–based physical therapist who specializes in helping women return to fitness after injury and pregnancy.

Peeing during activity is common for many women with a weakened pelvic floor — including women who have not given birth — but it can be prevented. (Surprise! The answer isn’t more Kegel exercises.)

These three core-strengthening drills are safe for pregnant women, though they can benefit anyone with a weak pelvic floor. Perform them three times a week, completing all reps of each exercise before moving on to the next.

Stability-Ball March

Illustrations by Kveta

Illustrations by Kveta- Sit on a stability ball, in good posture, with both feet flat on the floor.

- Engage and lift your pelvic floor away from the ball, as if you were trying to stop a stream of urine.

- Lift one foot under control a few inches off the floor and hold for a beat before returning your foot to the floor and switching sides.

- Perform as many reps you can with good form, up to 10 to 12 reps per side.

- Make the move more challenging by raising your arm straight up as you lift the opposite foot.

Hip Bridge

Illustrations by Kveta

Illustrations by Kveta- Lie down on your back, with your knees bent and feet flat on the floor and hip width apart.

- Place a ball about the size of a small soccer ball between your knees.

- Squeeze your glutes and bring your ribs down toward the floor.

- Drive down through your heels to lift your hips up until they form a straight line with your knees and shoulders. Keep your ribs down.

- Lower your hips to the floor under control and repeat.

- Perform 10 to 20 reps.

Pelvic-Floor Breath Squats

Illustrations by Kveta

Illustrations by Kveta- Stand up in tall posture, with your joints stacked and ribs down.

- Move your feet out to a width that feels stable in a squat.

- Inhale through your nose and lift your pelvic floor as if you are trying to stop a stream of urine as you sit your butt down between your heels.

- Exhale through pursed lips as you stand back up, relaxing your pelvic floor as you go.

- Perform as many reps as you can with good form, up to 10 to 15 reps per side.

This originally appeared as “More to the Core” in the October 2017 print issue of Experience Life.

This Post Has One Comment

Very informative and easy to follow. Thank you!