Heritage diets, or the way our ancestors ate, represent a powerful tool for both connecting with our roots and introducing nutritious ingredients into our lifestyles. Wherever your family’s roots lie, there’s abundant wisdom passed down through the generations: how to live, how to eat, and how to thrive in a community.

You may have examples of this from your own life, maybe in your grandma’s braised collard greens. Or the eggplant, potatoes, and peppers your father would stir-fry into di san xian, “three treasures from the ground.”

Fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains were once the cornerstones of traditional diets. Today, these whole foods make up only a small percentage of the standard American diet (SAD), which is heavily skewed toward refined starches, sugar, and red meat.

Studies show that a plant-based way of life is associated with reduced risk of cancer, heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity. Some may say this is a compelling argument that our ancestors were on to something in the food department. Reclaiming those roots could allow us to focus more on the foods that nourish our bodies and feed our souls.

That’s the mission of Oldways, a nonprofit organization that offers education in traditional foodways through courses, recipes, and other resources. In collaboration with doctors, dietitians, food scholars, and other experts, Oldways developed a series of heritage-diet pyramids to serve as illustrative guides for understanding how our ancestors ate.

Each pyramid represents the eating patterns of many different regions and cultures, yet they all have a lot in common.

“The plant-based or plant-forward pattern is the dominant feature of each of the heritage diets, and it is this pattern, rather than the specific foods or preparations, that defines the pyramids,” explains Oldways director of nutrition Kelly LeBlanc, MLA, RD, LDN. “This, in turn, provides the framework to describe the more specific foods eaten in a particular country or region.”

Ancient grains, vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, and seeds are the nutritious building blocks of each heritage diet. Leafy greens are prevalent, including China’s bok choy and India’s saag. Mustard greens are a staple both on the Indian subcontinent and in West Africa — and by extension, in African American cuisine.

Fish and seafood often appear in the next tier. The importance of fishing is reflected in the mythology of many cultures, especially in coastal and river regions. Today, research supports moderate fish consumption as a healthy way to incorporate protein, healthy fats, and other vital nutrients into your diet. (For more on making sustainable seafood choices, see “How to Find Sustainable Seafood“.)

In every traditional diet, these foods are the primary emphasis. Dairy and meat are less common, and sweets are reserved as an occasional treat.

You can see these similarities reflected in cuisines across the world — perhaps even in some of your favorite foods. “Think of all of the different types of bean-and-rice dishes — such as hoppin’ John with collard greens, Greek chickpeas and rice, jollof rice with black-eyed peas, or Mexican tomato rice and black beans,” says LeBlanc. “Or think of salsa: tomato, onion, peppers, spices — all foods that are part of the Mediterranean diet, and just like a Spanish sofrito.”

“Nutrition research has historically been Eurocentric, meaning that many people of color have been taught that the foods they grew up eating aren’t healthy, and that their culture or race puts them at a higher risk of health complications.”

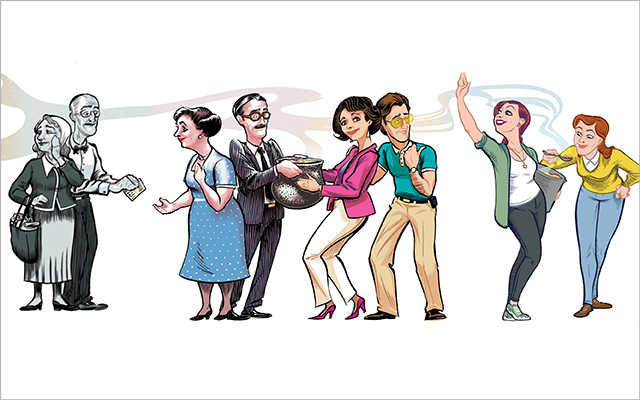

And there’s more to it than the foods we eat. How and with whom we share our meals are equally important. Heritage diets encourage us to spend time as a family and community — a lifestyle habit that’s less common in the convenience-driven SAD — and to incorporate movement, whether in the form of dance, martial arts, or simply taking a stroll through the park.

Heritage diets — and the many cultures they each represent — have a lot to offer for modern living, particularly to multiracial communities. “Nutrition research has historically been Eurocentric, meaning that many people of color have been taught that the foods they grew up eating aren’t healthy, and that their culture or race puts them at a higher risk of health complications,” LeBlanc explains. “Heritage diets empower both individuals and their community by restoring the culinary legacy and often-unsung cultural ownership of healthy eating for people of diverse backgrounds.”

Let’s take a closer look at some heritage diets and the ways they prioritize good food and good health.

1. Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean diet is the most well-known — and well-researched — traditional diet. Many are familiar with the virtues of extra-virgin olive oil, which is a fundamental component. High olive-oil consumption is associated with lower blood pressure, improved heart health, and a reduced risk of some cancers.

Mediterranean dishes are seasoned with herbs and spices like basil, rosemary, and sumac. Fish is regularly present on the Mediterranean plate, as are vegetables, nuts, and legumes. Wine consumption is kept to a moderate level, typically enjoyed with food as a digestion aid — and in community, among family and friends.

The traditional Mediterranean way of life also features plenty of walking, a form of exercise that improves both physical and mental health. (For more on this traditional foodway, visit “The Health Benefits of Eating a Mediterranean Diet” and try this grain-free, detox-friendly Mediterranean Quinoa Salad.)

2. African Heritage Diet

“The rich callaloos of the Caribbean, the collard and turnip greens of the southern United States, the use of leafy greens along with the consumption of their liquid, called pot likker — these are culinary connectors,” writes culinary historian Jessica B. Harris, PhD, in Bryant Terry’s Black Food: Stories, Art, and Recipes From Across the African Diaspora.

“The abundant use of okra in gumbos or soupy stews or simply eaten alone is another; just think of a sopa de quimbombó in Puerto Rico or Cuba.”

The African heritage diet features abundant vegetables, tubers, fruits, legumes, and nuts, and leafy greens form the base of the pyramid. In traditional sub-Saharan African diets, ancient grains like fonio, sorghum, millet, and barley are prominent.

Homemade spice blends, such as suya spice in Nigeria and mitmita in Ethiopia, and marinades are used to season dishes. Spices and spicy food are common across Africa and cuisines with African roots — spices around the world have a long history of both culinary and medicinal use.

3. Latin American Heritage Diet

The traditional Latin American diet is fiber-rich. Ancient grains, like maize and barley, and seeds, like quinoa and amaranth, play a major role. Popular health foods, such as chia seeds and spirulina, were staples of the Aztec diet.

“Most people have room in their diets to increase their fiber intake,” says dietitian Krista Linares, MPH, RD, who offers nutrition coaching through her California-based company, Nutrition con Sabor. “This can help with hunger and fullness cues, improves blood sugar and cholesterol, and is great for our gut health.”

For her clients, Linares often points to traditional Latin foods that provide fiber, like beans, lentils, and vegetables in the form of fresh salsa, diced onion, and cilantro. “This allows people to cook essentially the same meals they’re used to eating but add a bit of extra fiber and vitamins and minerals on the side.”

There is a misconception, particularly in the United States, that Latin American diets are unhealthy, she notes. “It’s easy to look at a Latin American plate and see mostly carbs and protein. But the vegetables are there, too.” And traditional Latin American cultures also included plenty of movement, often in the form of dance.

Food has long served as a social linchpin in Latin culture. Eating meals together may build positive family relationships while supporting mental health and fostering healthy eating habits.

4. Asian Heritage Diet

Whether you look to the east in China and Japan or to the south in India, Bangladesh, and their neighboring countries, the Asian heritage diet is rich in dark leafy greens, legumes, whole grains, and herbs. Major protein sources include legumes, such as soy; whole grains, like rice and pseudograin seeds like buckwheat; and plenty of fish and shellfish.

Many health-promoting superfoods have roots in various Asian cuisines: Think green tea from China, seaweed from Japan, and turmeric and ginger from Southeast Asia.

Poultry and eggs make occasional appearances on the traditional Asian table, and red meat is less common. In fact, many Asian cultures have ancient vegetarian roots, thanks to the practices of Buddhism, Daoism, Hinduism, and Jainism. Ancient wellness practices — tai chi, qigong, and yoga — encourage people to engage in meditative movements that provide a range of mind–body health benefits.

5. Native American Heritage Diet

Naturally, there are many similarities between Latin American and Native American heritage diets. The “three sisters” (squash, beans, and corn) have long been staples of Indigenous cultures across the Americas, often appearing in folklore that speaks to their cultural significance.

Today, they remain a fixture in many Native American dishes. “When we look at Indigenous food systems, we’re looking at commonalities of how Indigenous peoples were surviving with the world around them, primarily with plant knowledge,” says chef Sean Sherman, founder and co-owner of the Sioux Chef, an organization committed to educating the public about Native American foodways.

“When you look at the world around you with an Indigenous perspective, you see nothing but food and medicine and so much giving out there. The Western diet has largely ignored the bounty of the plant life that’s around us in North America.”

Before they were forced onto reservations, Native Americans built their diets on seasonal, regional ingredients and traditional hunting, fishing, and agricultural practices. There’s a great wealth of dietary diversity across different tribes and regions.

“When you’re following an Indigenous diet, especially of North America, it happens to be extremely low glycemic,” says Sherman. “There’s an immense amount of plant diversity, and it’s not overly protein- or sodium-heavy. It just becomes an ideal diet in general — almost like what most diets are trying to get to.” (Learn how Sherman is striving to decolonize America’s idea of food at “Sioux Chef Sean Sherman on the Importance of Indigenous Food”

This article originally appeared as “Back to Our Food Roots” in the September 2022 issue of Experience Life.

This Post Has 0 Comments