Melanie Swanson loved pizza and hot dogs ever since she was a kid. Green leafy veggies, salmon, and quinoa? Not so much.

Like many people who grew up on processed fare, “healthy” foods just didn’t taste as good to Swanson. She craved potato chips, mac and cheese, and soda, even though she knew they weren’t good for her.

So when a friend asked her to team up for a monthlong detox last spring, the 30-year-old photographer decided to go all in. For 30 days, she eliminated all processed foods and ate vegetables, lean meats, seafood, eggs, and certain fruits, plus plenty of healthy fats.

As the weeks passed, something unexpected happened: She started noticing the flavors of these real, whole foods.

“I discovered sweet potatoes, which I had always avoided because of their texture,” Swanson says. “Suddenly, I was eating baked sweet potatoes three days a week, and they tasted great.”

She even began eating fish, which she had long avoided. She found herself appreciating the simple pleasure of a mixed green salad dressed with homemade vinaigrette, instead of her usual dose of store-bought ranch dressing.

And after a month of healthier eating, something else caught her by surprise: Some of the processed foods she used to love just didn’t taste nearly as good. “I had a box of Girl Scout cookies around the house, so I decided to treat myself,” she says. “That Samoa was so sweet — really overly sweet.”

Swanson’s experience of a newly awakened palate is not unique.

“It’s never too late to get your taste buds back on the right track,” says Rebecca Katz, MS, director of the Healing Kitchens Institute at Commonweal and author of The Healthy Mind Cookbook. “We’re born with an inherent ability to taste real food on a deep level.”

The good news, Katz says, is that no amount of processed food will permanently alter that. And once your palate is back on track, it will steadily guide you toward healthier (and tastier) choices.

The Biology of Taste

Get a mirror, stick out your tongue, and say hello to your taste buds, all 10,000 of them. Those small bumps on your tongue, roof of your mouth, and throat are called papillae, and each of them is home to up to 700 taste buds. And each tiny taste bud contains about 50 to 80 specialized taste-receptor cells.

When a taste receptor recognizes a flavor — sweet, salty, sour, bitter, or umami (savory) — it sets off a biochemical reaction called transduction, translating chemical information from the taste stimulus into an electrical message that travels through the cranial nerves to the gustatory cortex of your brain.

Taste buds help set your body’s metabolic machine in motion, as does your sense of smell. (Chewing releases molecules from food at the back of your throat up into the retronasal passage, sending signals to your brain’s olfactory cortex.)

Based on the messages it receives, your brain cues digestion, sending signals via the vagus nerve and triggering what is known as the cephalic phase response: Take a tiny taste of barbecue sauce before the picnic even begins, and your brain is already releasing insulin and directing your digestive tract to secrete as much as 40 percent of the hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes you’ll need to process the food you’re about to have.

In addition to kicking off the digestive process, your sense of taste serves as a security system of sorts for your body. More DNA is dedicated to the sophisticated flavor-sensing equipment in your mouth, throat, and nose than to any other bodily system — including your brain and eyes, says journalist Mark Schatzker, author of The Dorito Effect: The Surprising New Truth About Food and Flavor.

This makes sense when you consider that our earliest ancestors wouldn’t have survived long if they weren’t able to avoid foods that could harm them and identify foods that met their nutritional needs. It’s thought that we’re genetically programmed to be wary of bitter-tasting foods, for instance, because bitterness can be an indicator of plants that are poisonous.

Natural survival instincts also prompt us to seek out foods that are salty, because our bodies require sodium to support nerve and muscle operation. In addition, we’re hardwired to seek out calories for energy and fats, which support brain functioning, says Linda Bartoshuk, PhD, a nutrition professor at the University of Florida.

Taste Buds Led Astray

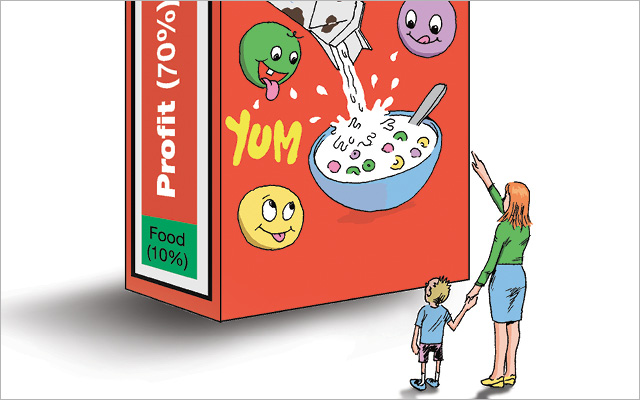

What served us well on the savannah is sabotaging many of us today. The biological mechanisms that are supposed to steer us toward healthy choices have been thrown off course by a mind-boggling array of synthetically flavored processed foods.

“We used to get the flavor in our food from plants and animals, and now we get it from factories,” says Schatzker. (For more on how synthetic flavors have infiltrated our food, see “The War for Our Taste Buds,” below.)

Trying to satisfy our inherent cravings for sugars, fats, and sodium with hyperflavored convenience food fails to meet our health and nutrition needs — and actually makes us crave even more processed foods.

That’s because the novelty of amped-up flavors appeals to us more than eating the same old foods every day. Food manufacturers use the term “sensory-specific satiety” to describe the phenomenon in which pleasure derived from a known food declines in comparison with more novel flavors.

Sugar, fat, and salt also activate regions in our brains associated with desire and reward. Food manufacturers know this, and they are constantly creating complex flavors and textures that are specifically and expressly designed to be irresistible.

Our cravings for these fake flavors become part of a seemingly endless cycle. Eating too many refined carbs and sugars, for example, can cause a spike in blood-sugar levels called postprandial hyperglycemia, a quick rush (and subsequent drop) of insulin that leaves you feeling sluggish afterward — yet still strangely hungry.

Studies further suggest that foods loaded with trans fats promote excretion of the stress hormone cortisol, which stimulates appetite, driving you to eat even more calorie-dense foods. (For more on how processed foods bamboozle our taste buds, see “Scary Food Science“.)

“The food industry has been clever to tap into mechanisms that are already present in our systems for good reasons,” says Bartoshuk.

Rather than beat yourself up because you crave your favorite boxed mac and cheese or toaster pastry, remember that our desire for satisfying foods is just part of human nature. “Eating has as much to do with nutrition as sex has to do with procreation,” says Schatzker. “We eat for one reason — because we love the way food tastes.”

The good news is that you can consciously reprogram your palate in the service of your health. These six strategies can help you reawaken your body’s built-in nutritional wisdom — and your taste buds.

6 Ways to Reclaim Your Taste

Strategy 1: Cleanse your palate.

Whether you gradually ease off highly flavored processed foods or eliminate them all at once, your sense of taste will eventually become more attuned to subtler flavor variations.

You might notice a difference within just a few weeks of eliminating the bad stuff, says Jo Robinson, author of Eating on the Wild Side: The Missing Link to Optimum Health. “After a while, you’ll begin to taste things such as the natural sodium in vegetables that you’ve never tasted before.”

One way to jump-start this palate cleansing is to serve yourself the good stuff first: Eat your veggies before digging into the other food on your plate, giving yourself the opportunity to savor their delicate tastes and textures.

Strategy 2: Slow down.

People are used to eating foods that are so highly processed that they don’t take much effort or time to be consumed. Food-texture expert Gail Vance Civille says that her research in the 1960s and 1970s showed that most steaks required chewing up to 25 times on average before being swallowed. Now, “consumers are most comfortable with foods that are chewed only 10 to 15 times,” she says.

To bring out the full flavor of what you’re eating, chew slowly and mindfully. This will also aid with digestion and help you get the most nutrition out of your food.

Strategy 3: Try something new.

If you’re trying to introduce your taste buds to sensations beyond salty and sweet, broaden your horizons with food from one of the other taste categories at each meal: sour (citrus, sauerkraut); bitter (turmeric, dark chocolate); and umami, the rich, meaty taste found in mushrooms, tomatoes, and red meat. (For more on umami, see “Umami: The Secret Flavor“.)

“Processed food numbs the taste buds, but indulging in true flavor can help reclaim them,” chef Rebecca Katz says. She uses the mnemonic acronym FASS as a reminder to include healthy fats, taste-bud-brightening acids, flavor-enhancing salt, and mellowing sweetness in every meal. (For more on FASS, download this PDF.)

Strategy 4: Make a positive connection.

Remember that fun gathering with your new neighbors, when you amiably tried baba ganoush for the first time? It turns out that recalling happy times associated with tasting nutritious foods can help you acquire a new taste (even for eggplant!).

We learn to like foods through positive associations, says Traci Mann, PhD, psychologist and author of Secrets From the Eating Lab: The Science of Weight Loss, the Myth of Willpower, and Why You Should Never Diet Again.

So just because you couldn’t stand overcooked peas in your school lunch doesn’t mean your taste buds won’t flip — eventually — for freshly shucked peas from the farmers’ market.

Strategy 5: Get your brain on board.

“Looking forward to eating a food you love provides real pleasure,” says Mann. So allow yourself to build up a sense of anticipation, especially if you’re about to eat a food you particularly enjoy.

And if it’s a food you don’t normally like, warm up the analytical part of your brain instead. Set out to collect some interesting data — about its health benefits, texture, flavor, temperature — that might help you overcome your initial aversion.

Strategy 6: Try and try again.

Research has shown that repeated exposure can increase how much you like a particular food. And while that’s a good reason to keep dishing up spinach to your kids at dinnertime, it’s a course of action that can work just as well for you, too.

“The more times you eat something, and the more times you enjoy a happy moment while eating that food, the more you’ll end up liking it,” Mann says. “For some bitter foods, it might take up to 20 separate tastings before your taste buds finally learn to like it.”

Try different preparations to see if you find one tastier than another. For example, if you don’t care for roasted beets, try eating them raw in a salad.

The War for Our Taste Buds

To win our grocery dollars, processed-food manufacturers have invested millions in captivating us with turbocharged flavors, delectable fats, irresistible crunchiness, and other seductive textures. Phenomena such as Doritos Jacked Ranch Dipped Hot Wings tortilla chips epitomize what journalist Mark Schatzker calls “flavor dose creep” in modern foods.

In his book The Dorito Effect, Schatzker states that whole foods began tasting blander beginning in the mid-1960s, when large-scale corporate farming and nationwide grocery-store distribution replaced local, farm-fresh goods. Authentic taste was the first casualty of foods super-bred for mass production, cross-country transportation, and shelf stability.

“The food we eat comes from farms and breeding facilities focused on productivity, affordability, and disease-resistance, but not on flavor,” Schatzker says.

As natural flavor suffers, so does nutrition: Schatzker cites a 2004 study in the Journal of the American College of Nutrition showing that modern tomatoes have half as much calcium and vitamin A as they did in the 1950s.

During this same era, the technical sophistication of synthetic flavorings took off. “Flavors that used to be in foods you’d get from a farm were being produced in food-processing factories,” he says. The result can be seen in the modern grocery store, where you might struggle to find a truly tasty tomato but can savor its zesty synthetic counterpart in a bag of ketchup-flavored potato chips found in the next aisle.

Americans are increasingly choosing the fake over the real. As a nation, we now consume more than 600 million pounds of synthetic flavorings a year, Schatzker says — about 2 pounds per person.

The flavor of fresh-picked berries or carrots used to be our signal that food was nutritious. Now, our thrill-seeking taste buds drive us to crave foods that provide little in the way of nutrition but lots of jazzed-up flavor. When you’ve been riding the roller coaster of lab-concocted taste sensations, it can be a challenge to opt instead for a quiet walk through the vegetable garden.

This Post Has One Comment

I live in South Africa. Your site does not allow me to type the location. I live in a semi desert area. We grow all our own vegetables. We have sheep and cattle wich we use as our own meat supply. We have lots of game, (various antelope, mainly gemsbok ,(Oryx), springbuck, etc) which we hunt during winter. I never take sugar or milk in my coffee. I don’t drink soda drinks. I don’t eat any sweet foods but we grow watermelons & I love those. We also grow quince, spinach and lots more. We use margarine, I love to have a cold glass of full cream milk every evering. I aways crave salt, & bitter tastes. I love to eat thick skinned lemons from the tree like an apple with skin and all plus lots of salt. I love spinach mixed with tomato, onion, potato and mince. I also love curry foods with lots of chilli. I am 5.6ft tall, weight is 52kg, 62 years old. I am telling all this because lately, (last 8 to 9 months ), I crave for tastes I don’t usually like. Super sweet condensed milk from the tin mixed with cruched lemon cream biscuits. Chicken baked with apricot jam and mayo. Help me, I never loved these sweet stuff. Why did my tastes change?