As a kid growing up in New Jersey, I always watched the Olympics. And in 2006, after swimming for North Carolina State University, I found myself in the pool alongside Michael Phelps at the Pan Pacific Championships, where he beat me by 1/10th of a second. By 2007 I had made the U.S. World Championship team.

It was the next year, in 2008, that I found myself in a rut and decided to do something unorthodox. If I was going to make the Olympic team, I knew I needed a change.

I called the coach for the national team, and he told me I needed to train with the Olympic-level coach in Charlotte, N.C., about three hours away from where I was living in Raleigh. It was nearly midnight when I finished that call, and I left that night without telling my coach at N.C. State, who thankfully understood.

At practice with my new coach the next morning, I realized I was rusty — my metabolism had slowed down and I wasn’t eating as healthy as I should have been. So, I buckled in for a whirlwind of training, revamped my eating, started lifting weights, and ramped up important skills like visualization and staying present in the moment.

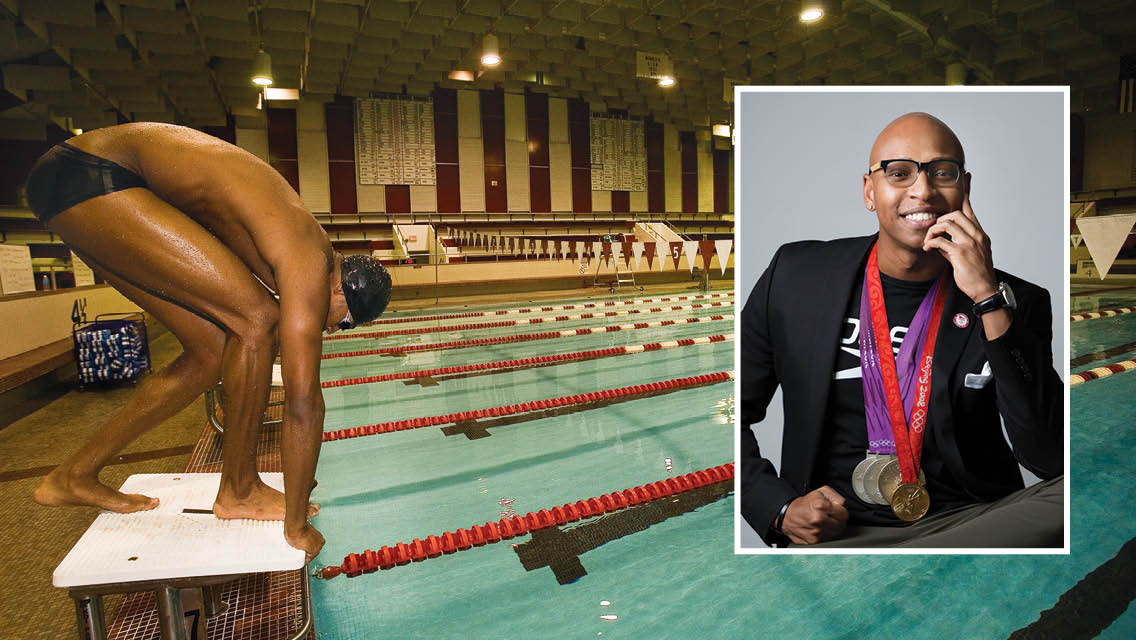

Two months after arriving in Charlotte, I went to the Olympic trials, made the team, and went on to win a gold medal as part of the 400 free relay team.

The first thing I did was thank my coach at N.C. State for empowering me to do what was best for me and to be the best athlete I could be. Given my childhood experiences in the pool, winning a gold medal wasn’t something anyone could have predicted — especially since I nearly drowned at age 5.

My Swimming Scare

My dad has always been my mentor, and I always wanted to follow in his footsteps and do as he did. So, when he told me he was going down the waterslide at Dorney Park and Wildwater Kingdom in Allentown, Penn., I was right behind him.

At the time, I was 5 years old, but I still remember what my dad had told me: “Whatever you do, don’t let go of the inner tube.” In fact, he said it twice.

My dad went first. Then, almost as quickly as my ride had begun, I hit the water and flipped upside down, unable to pull myself back up. Time had to have passed slowly . . . 29, 30, 31, 32. I was stuck underwater for 30 to 35 seconds — an amount of time that can cause brain damage in children.

The next thing I knew, I had been rescued by a lifeguard. And I had one question: What ride are we going on next?

My mother (who had not been far behind me on the waterslide and subsequently nearly drowned herself while trying to save me) was the one to immediately insist I take swimming lessons. Looking back, I realize how bold a decision that was; it would have been so easy for her as a protective mother to swear off swimming altogether.

I absolutely bombed my first lesson. I cried. I hated being in the water, and I told my mom I needed a new teacher. It took five different teachers until I felt comfortable — and by that time I was 8 years old. Little did I know I was already building the empathy I would need to later teach others to swim.

Around the same time, my passion and competitive drive for swimming began. I remember watching other kids racing, and I was drawn to it immediately. In my head, I believed I could beat them.

Did that happen? No. At the time, it may have been hard to believe that I would eventually be a four-time Olympic medalist and the second African American in history to win an Olympic gold medal in swimming. But I was having fun, and it was an outlet where I could control my progression. So I kept swimming.

Creating Positive Change

I swam throughout high school, even though most of my classmates — the majority of whom were Black or Latinx — played football or basketball, or ran track. I would often end up in the weight room at the same time as the school’s basketball team, many of whom didn’t necessarily see swimmers as athletes. I always took joy in surprising them with my bench-press and pull-up skills.

Many of my classmates also didn’t see a place for themselves in swimming, and during my time training for the Olympics, I had been so focused on representing my team and competing that I hadn’t processed the fact that I was going to be a role model for young swimmers of color.

I was living in New York City at the time, and it wasn’t until I got back home that it really hit me. When I was growing up, no Olympic swimmers looked like me, and now I was able to show young people what was possible.

I believe that creating change and making the sport more inclusive starts at the grassroots level. There is a stereotype that Black people don’t swim, which is rooted in the very real fact that we were not always allowed access to public pools. So, when you’re teaching a person of color, you’re often reprogramming their mindset — and even the mindset of their family.

Looking Toward the Future

Swimming and fitness are still a huge part of my life. Especially during the pandemic, I’ve realized how essential activity is to my well-being when the world can be so unpredictable.

I’m currently working with Speedo as the philanthropic sales manager; I lead its fundraising initiatives, enhance its relationship with grassroots teams, and develop its community-support strategy.

I’ve also been working with the USA Swimming Foundation’s Make a Splash initiative for the past 12 years, teaching others, especially children of color, how to swim. The program promotes water safety by providing free swimming lessons to children from disadvantaged communities. We’ve helped reduce the number of African Americans with little or no swimming ability from 70 percent in 2007 to 64 percent today.

Along with this work, I spend a good chunk of time at events and colleges speaking about overcoming challenges and the powerful and transferable life skills common to athletes, like growth mindset, time management, and motivation.

I want to work hard now so I can spend as much time as possible with my family in the future. Also — and I want this to be in print, so I hold myself to it! — I want to travel for my 40th birthday, be fit, and look great in a black T-shirt.

Swimming is for everyone, and it’s an essential life skill. This is the same approach I take with my 2-year-old son, Ayvn — he just needs to learn to swim. He doesn’t need to be an Olympic athlete; I just want to know that when we’re near water he’ll be safe.

Cullen’s Top 3 Success Strategies

- “Strive for perfection but settle for first place.” It’s easy to beat yourself up, but remember to give yourself some grace. Work hard and be proud that you laid it all out there.

- Focus on your goal. When you swim, there might not always be people who look like you or who you can relate to, he says. But if you keep your focus on your progression, you’ll grow as a person and you might even change your life.

- Know when to be relentless. Cullen’s mom insisted he learn to swim. Not only was it an extremely important life skill, but it was the reason he became a four-time Olympic medalist.

Tell Us Your Story! Have a transformational healthy-living tale of your own? Share it with us!

This article originally appeared as “Welcome to the Water” in the June 2021 issue of Experience Life.

This Post Has 0 Comments