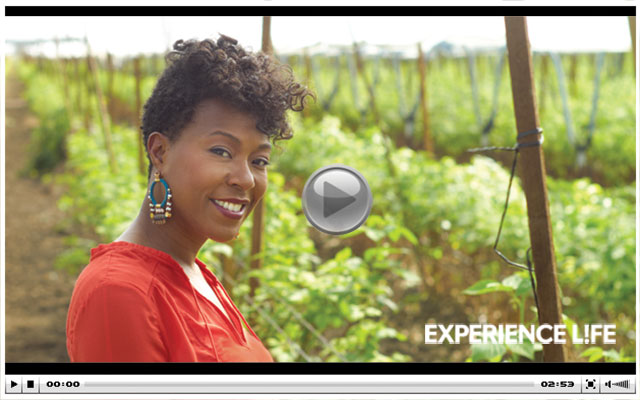

Robin Emmons wasn’t born a farmer. Or a healthy-food advocate. The 46-year-old stepped into both those unlikely roles later in life.

“No one who knew me 25 years ago can believe that I’m actually in this space,” she says.

Seven years ago, Emmons ditched her cushy bank job in Charlotte, N.C., without any clear plan of what she wanted to do next.

A week later, the purpose-centered work she’d been seeking suddenly found her. Emmons’s brother — who suffers from mental illness and had been homeless for a decade — needed help moving into a care facility. Once she got him settled in, though, Emmons began to notice that the food he was being fed seemed to be making him sick.

Already a weekend gardener, Emmons responded by tearing up her entire backyard and transforming it into a mini-farm so she could grow food for her brother’s facility. Once her produce was incorporated into meals there, her brother’s health soon improved, and Emmons then turned her attention to other underserved populations.

A student of anthropology, Emmons began researching how Americans had become disconnected from their food — and from one another. She discovered that vast numbers of America’s urban poor live in “food deserts” — neighborhoods where grocery stores are rare or nonexistent.

Emmons realized that despite Charlotte’s burgeoning local-food movement, many low-income people in her own community had been left without a seat at the table. Food deserts abounded. And wherever families had to rely on fast-food chains and convenience stores for their meals, the health consequences were dire.

So in 2008, Emmons became founder and executive director of Sow Much Good, a nonprofit that helps low-income people access healthy, homegrown food and avoid what Emmons refers to as “nutritional starvation.”

She has been getting her hands dirty ever since, working sunup to sundown to put whole, healthy foods within reach of those who need them most.

Sow Much Good has now grown to include two microfarms that have distributed 32,000 pounds of food directly to the lowest-income residents of the Charlotte area. And Emmons is just getting started.

Experience Life | Why do you say food is a social-justice issue?

Robin Emmons | Food is a fundamental need. It’s the responsibility of all of us to ensure that everyone has access to healthy, fresh food. Each of us can make sure that everyone has access through the choices we make: We can grow our own food, support local farmers, and donate time to organizations working on food-access issues.

EL | What are some of the biggest obstacles to obtaining fresh food for people living in marginalized communities?

RE | Geographic location has everything to do with the way people eat. If you’re a mom with three kids working a low-income job and you don’t have a car, but there’s a corner store or gas station in your community that has a package of pink hotdogs and a loaf of white bread, then that’s what’s for dinner. Also, if you haven’t been exposed to a resource in your community like a farmers’ market, visiting one can be intimidating at first.

EL | “Food deserts” are often “nature deserts,” too. In your work, you’ve taken a hands-on approach to addressing both. Why do you feel growing your own food and interacting with nature is so important?

RE | Ron Finley, the Los Angeles guerilla gardener, said it best: “Growing your own food is like printing your own money.” Growing your own food provides you with some security. It also ensures your food’s integrity and nutrient density.

Gardening also shows us that we’re not separate from nature. I believe spending so much time in artificial environments is part of what’s making us overweight and unhealthy.

EL | How did going from working in an office to working predominantly outdoors affect your health?

RE | When I was working long hours in the corporate space, I was sick in so many ways. My health has improved by leaps and bounds, and my joy has increased exponentially. Physically, I get plenty of exercise farming the land, and I certainly get my supply of vitamin D.

My mental and spiritual health has improved because growing food and being in nature is calming. Gardening and farming are meditative processes. I witness nature in action every day. Seeing a seed sprout into a seedling into a plant into a flower and into a fruit is a miracle.

EL | Sow Much Good is committed to sustainable growing practices. Why?

RE | I think we’ve pushed our planet’s ecosystems to the point of obliteration, so I believe in using practices and processes that respect and honor the earth, animals, and people.

At all our growing sites, we use chemical-free methods. We try to create healthy ecosystems by bringing in chickens, bees, and beneficial insects; by capturing rainwater, using solar energy, and rotating crops; and by planting cover crops to nourish the soil.

It’s ironic that we have to go to such great lengths to create the balance and symbiosis inherent in nature. Things were perfectly balanced before we inserted ourselves in the process and began growing things in the interest of profit.

EL | How has doing this sort of hands-on gardening and farming work changed you, and how do you see it changing other people?

RE | We’re taught to think of ourselves as individuals and to focus on accumulating wealth. This discourages us from understanding our common humanity and our interconnectedness, and it causes much of the loneliness, suffering, and isolation many people feel.

Nature reminds us that our inexplicable bond to other humans can’t be broken. When you take a seed and drop it into the earth, you start to see things differently. You realize that you’re getting something that will sustain and nourish you, and also something that you can so easily share with others. Nourishment is a multidimensional affair. It’s not just about the food we eat. It’s also about our connection with one another.

EL | What kind of outreach are you doing to get these whole foods into the hands of the people in need?

RE | We host “satellite” farmers’ markets in the neighborhoods we directly serve, and last year we introduced a low-income community-supported agriculture [CSA]option where people get a box of fresh food every week. I’m especially excited about this because we haven’t seen CSAs in underserved communities before. They just haven’t been affordable.

We had an initial goal of getting 25 families to join — we got 50. And this year, there are 100 families signed up. It’s so rewarding to see the people coming and taking advantage of all these options.

EL | What advice can you offer for those growing their own food for the first time?

RE | Start small. Don’t rip up your entire backyard the way I did! You’ll just be overwhelmed. Remember that small space doesn’t mean small yields. Start with a few plants in containers on your balcony or deck. There are things you can buy or build that allow you to grow things vertically, too. If you want more instruction or group interaction, get involved with a community garden, purchase a CSA share, or volunteer with a local farmer.

This Post Has 0 Comments