If you haven’t yet experienced lower-back pain, the bad news is, you probably will. Roughly 80 to 90 percent of Americans suffer lower-back injuries at some point in their lives. Not only are these injuries painful and debilitating, but they also cause secondary problems. Specifically, when the muscles primarily responsible for stabilizing the lower spine — known as local lumbar stabilizers — become deactivated, the result is a cascade of muscle imbalances spreading throughout the body, reduced mobility and physical performance, and increased risk of future injuries.

And unlike other, more superficial, back muscles, your local lumbar stabilizers stay deactivated unless you reestablish their connection to your brain. Luckily, it’s relatively easy to get back on track.

It’s a Core Concern

Our local lumbar stabilizers tend to remain inactive because we sit so much, and other muscles do the work of keeping the torso upright. “Because it’s being underused, the musculature that’s supposed to stabilize the spine becomes weakened,” says Staffan Elgelid, PT, PhD, assistant professor of physical therapy at Arkansas State University in Jonesboro.

This lack of stability usually affects one side more than the other. “If one side of the low back is unstable, it moves too much,” says Michael Clark, DPT, PT, PES, CES, president and CEO of the National Academy of Sports Medicine. “Then the other side locks down, creating a compressive pathology that breaks down the cartilage around the facet joint, causing swelling, which pushes on the nerve in that area and causes pain.”

That swelling and pain tell the brain to deactivate the affected muscles, explains Clark, team physical therapist of the Phoenix Suns. As a result, they quickly atrophy, and other muscles, such as the psoas (which connects the lumbar spine to the upper thigh), are forced to assume the job of protecting the lower back. But these muscles really weren’t designed for that role. “Your psoas is normally a pretty powerful hip flexor,” says Clark. “But if it has to create stability at the lumbar spine and flex your hip, it’s like driving with your parking brake on.” For athletes and active individuals, that means compromised performance and increased risk of other injuries, such as hip flexor tendinitis.

Back to Basics

Research has shown that the local lumbar stabilizers remain shut down unless their connection to the brain is reestablished. In 1996, a team of Australian physiotherapists led by Julie Hides, PhD, popularized a simple technique to reactivate these muscles, variations of which physical therapists around the world now practice. The technique involves “locking” your lower spine into a stable, neutral position with isometric contractions of the targeted muscles, while performing basic actions with other parts of the body (for examples, see “Reconnecting With the Brain,” below).

Isometric contractions are the quickest and surest way to reawaken the connection between the local lumbar stabilizers and the brain, and most mimic the work of postural muscles, Clark says. “When your stabilizers fire, the muscle spindles send a message to your brain, which sends a message back, creating a feedback loop that creates positive dynamic stability.”

Because the first step is just reestablishing communication, not strengthening, results can occur very quickly. “It’s almost like flipping a switch,” says Elgelid. “You can regain control of these muscles in a matter of days and bring them back to full strength in just a few weeks.”

Check Your Core Stability

How do you know whether your local lumbar stabilizers are functioning properly? Try the overhead squat test.

- Stand in front of a mirror wearing a pair of shorts.

- Lift your arms straight overhead and slowly squat down. “If you have good core stability, you should be able to squat down to the height of a chair without your feet caving in or turning out, without your knees coming together, and without your spine moving forward, your low back arching, or your low back rounding,” says Michael Clark, DPT, PT, PES, CES, president and CEO of the National Academy of Sports Medicine and team physical therapist of the Phoenix Suns.

- Movement at the feet, knees or spine may indicate that your deep abdominal and lower-back muscles aren’t able to properly stabilize your lumbar spine, and other muscles are being called upon. To be sure, ask a personal trainer or physical therapist to assist you.

Reconnecting With the Brain

These exercises coax your local lumbar stabilizers to reestablish communication with your brain. Despite their simplicity, though, it’s best to learn them under professional supervision. “Get a physical therapist to work with you for the first few sessions to perfect your technique,” says Staffan Elgelid, PT, PhD, assistant professor of physical therapy at Arkansas State University in Jonesboro. Do 10 to 12 reps of each exercise once a day, four to five times a week.

Transversus Abdominis Crunch

- Lie face up on the floor with your knees bent and feet flat on the floor.

- First, find your neutral spine position by rotating your pelvis as far forward as possible and then as far back as possible, then “locking” your spine in a comfortable position halfway between the extremes. This effort to hold your spine steady in the neutral position activates your transversus abdominis.

- Begin with your arms resting at your sides.

- Take a deep breath and exhale. As you exhale, extend both arms directly overhead, keeping your abs tight.

- Reach your hands farther toward the ceiling by lifting your head and shoulder blades off the floor a couple of inches. Pause for one or two seconds in this position and relax.

- Repeat the movement until it’s no longer possible to maintain a neutral spine.

Multifidus Stabilization

- Lie face up on the floor with your right leg extended on the floor and your left leg bent, foot flat on the floor and arms at your sides.

- Lock your lumbar spine into the neutral position as described above and tighten your buttocks.

- Raise your right foot just 12 inches above the floor, keeping your knee straight, and hold for three seconds.

- Relax and repeat 10 times. Reverse the position of your legs and lift the left leg 10 times.

Bridge and March

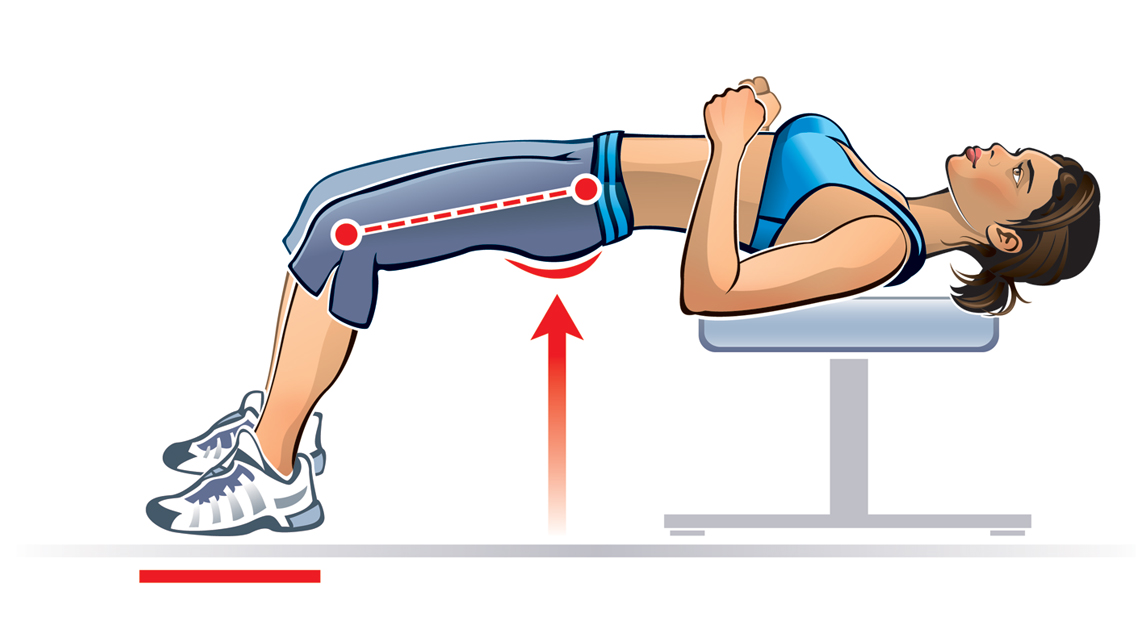

This exercise activates the transversus abdominis and the multifidus, as well as other important lower-back stabilizers.

- Lie face up on the floor with knees bent and feet flat on the floor, arms resting at your sides.

- Lock your lumbar spine into the neutral position as described above.

- Tighten your tummy and lift your hips upward until your body forms a straight line from your knees to your neck. Keep your arms relaxed on the floor.

- Pause briefly, then lift your right foot several inches above the floor. Pause for a second, then lower it back to the floor in a gentle marching motion.

- Concentrate on keeping your hips high and preventing your spine from rotating while performing this action.

- Alternate marching with the left leg until you’ve done eight to 10 reps with each leg.

Finesse your bridge form at “BREAK IT DOWN: The Glute Bridge“.

Back-Up Data

Everyone knows what the biceps are, but not many of us know what — or where — a local lumbar stabilizer is. Here’s a look at the location of two key muscles for lower-spine stability.

Transversus Abdominis — The deepest abdominal muscle connects the ribcage to the hipbones and stabilizes the trunk during lateral flexion (i.e., side bending).

Lumbar Multifidus — This is the muscle that connects the separate vertebrae of the spine, in two- to five-disc segments called fascicules. The multifidus extends and rotates the spine, and also stabilizes the spine when other joints are moving.

This article originally appeared as “In Search of Stability” in the March 2008 issue of Experience Life.

This Post Has 0 Comments