After following the USDA’s Dietary Guidelines all her adult life, Adele Hite was 60 pounds overweight and miserable. For years she’d filled her plate with the grains and low-fat dairy foods the government advised, but she was always hungry and tired.

During a routine check-up, her doctor told her she needed to “eat less and exercise more.” The 47-year-old mother of three, who is currently getting her PhD in nutrition epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, recalls her reaction well: “I burst into tears in the exam room.”

The physician’s assistant tasked with calming Hite listened to her story and suggested she try something different — eating more high-quality proteins and fats and cutting back on refined grains. So, in addition to emphasizing more vegetables, she started eating a variety of foods, such as eggs, that she once thought of as unhealthy because of their saturated fat content. To her amazement, over the course of two years, she lost all of her excess weight without feeling hungry. Now, 10 years later, she’s kept the weight off.

“Not until I started reducing the highly processed grains and cereals the Dietary Guidelines were built on did I finally get healthy,” she says. “I wonder how many other people those guidelines are failing.”

Apparently, a lot. In the 30 years since the debut of the USDA’s Dietary Guidelines, the number of Americans considered obese has skyrocketed from 15 percent to more than 34 percent. The leap occurred even as Americans shifted their diets to match the USDA’s advice to eat more grain-based carbohydrates and limit saturated fat.

The Dietary Guidelines consist of nutrition advice compiled and jointly issued every five years by the Departments of Agriculture (USDA) and Health and Human Services (HHS). The federal government released the most recent edition, the 2010 Dietary Guidelines, in early 2011.

In June, the infamous food pyramid was replaced with MyPlate, an icon resembling a dinner plate. The plate is divided into quadrants of various sizes. There is one section each for fruits, grains, vegetables and protein, with a serving of dairy on the side.

Both MyPlate and the Dietary Guidelines are meant to promote healthy eating. As with previous iterations, the question is, will they?

Reactions are mixed. The latest set of guidelines has been criticized for being too lax about some unhealthy foods (like refined grains) and lauded for encouraging Americans to embrace more nutrient-dense foods and drink fewer empty calories, including soft drinks.

But even if you have no intention of walking in lock step with the USDA’s dietary advice, you’d be wrong to dismiss the guidelines as inconsequential. Among other things, the USDA’s Dietary Guidelines set the framework for federal nutrition policy. As such, they dictate what food is made available to millions through the National School Lunch Program; Women, Infants, and Children Program; and Child and Adult Care Food Program.

And even if you aren’t directly influenced by such programs, the Dietary Guidelines probably still have a significant impact on your eating. That’s because every food maker in America keeps a watchful eye on the guidelines and adjusts their product formulations accordingly. The results trickle down to grocery shelves and restaurant menus in short order.

Of course, you still have plenty of choices to make. That’s why we asked some trusted nutrition experts to help us digest the most notable new dietary recommendations. Consider their “no-nonsense analysis” and “safe-bet advice,” then decide for yourself whether you want to adjust your eating, and how.

1. The New Guidelines Say: Reduce the intake of calories from solid fats and added sugars (SoFAS).

No-Nonsense Analysis

With the new guidelines, the USDA coined a new acronym: “SoFAS” — short for solid fats and added sugars. It’s a term that has even food experts a bit baffled. “I don’t know what ‘solid fats’ means, and I’m a nutritionist,” says Kristin Wartman, a certified nutrition educator and food writer.

What the USDA means by “solid fats” is fats that are solid at room temperature — a grab-bag category of nutritionally diverse fats such as butter, lard, coconut oil and partially hydrogenated oils (trans fats). Some food experts take umbrage at the lumping together of natural fats, like butter and coconut oil, with highly processed and toxic trans fats.

“Butter and even lard can be used in a healthy way,” says Wartman, while trans fats categorically cannot. “Many of my clients crave poor-quality fatty foods, like French fries or chips, because they are deficient in high-quality fats, like those found in fish, nuts, eggs and grass-fed dairy products. When I recommend they switch to good, clean sources of fat, their unhealthy cravings usually go away.”

But the bigger issue, for many experts, is what they see as the guidelines’ longstanding obsession with — and hamhanded advice about — fats in general, solid or otherwise.

“The total fat content of a given food or diet is a useless metric,” says Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, PhD, codirector of the Program in Cardiovascular Epidemiology at Harvard, “because there are healthy and unhealthy fats.”

“The total fat content of a given food or diet is a useless metric,” says Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, PhD, codirector of the Program in Cardiovascular Epidemiology at Harvard, “because there are healthy and unhealthy fats.” Instead of people worrying about specific nutrients, like fat, and whether or not certain fats are solid at room temperature, he would prefer people focus on simpler goals, like getting the majority of their fats from whole foods.

The second half of SoFAS is “added sugars.” You’d be hard-pressed to find a nutritionist who doesn’t think reducing added sugars is a good idea. Most especially like that the new guidelines encourage consumers to “drink water instead of sugary drinks.” (Sweet drinks, including soda and fruit juice, account for about 35 percent of added sugars in the American diet.)

“We’ve been so focused on saturated fats that we’ve lost sight of the fact that excess sugar drives up insulin levels and increases inflammation,” says David Katz, MD, director of the Yale University Prevention Research Center.

But many nutrition experts are concerned that the focus on “added sugars” might distract people from the fact that refined and processed flours act very much like sugars in the body, and have a similar negative effect on insulin levels and inflammation.

“I worry less about someone eating a 100 percent whole-grain product with a touch of added sugar than I do about them eating a refined-flour product that contains no sugar,” says Mozaffarian.

Others worry that consumers may interpret the advice to eat fewer added sugars as permission to eat more artificial sweeteners. That would be problematic because calorie-free sweeteners like aspartame, saccharin and sucralose can be up to 1,300 times sweeter than sugar itself, and they tend to disrupt the body’s natural insulin-regulating and calorie-counting mechanisms. In the end, the body cultivates a preference for sweetened foods coupled with a desire for satisfaction that never comes.

“When people rely on artificial sweeteners, they tend to prefer all of their other foods sweeter, from pasta sauce to salad dressing, because that exposure propagates a sweet tooth,” says Katz. For this and other reasons, numerous studies suggest that artificial sweeteners negatively affect weight loss.

Safe-Bet Advice: Avoid trans fats, excess sugars and refined grains. Embrace heathy fats from whole foods. Don’t rely on artificial sweeteners.

2. The New Guidelines Say: Consume less than 10 percent of calories from saturated fatty acids by replacing them with monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids.

No-Nonsense Analysis

The nutritionists we consulted leveled two key criticisms at this guideline: (1) It’s overly fussy and (2) based on outdated science.

On the fussy front, asking people to calculate percentages and differentiate between mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids unnecessarily distracts from a more important message, says Mozaffarian, “which is to eat more whole foods and avoid processed ones.”

Avocados, nuts, seeds, coconut, fish and full-fat dairy all contain healthy fats, he says. And processed foods packed with industrial vegetable oils may by high in polyunsaturated fats, but that doesn’t make them good for you.

“The percentage of calories from fat in a diet has no bearing on weight loss or any other major health outcome,” says Walter Willett, MD, chair of the department of nutrition at Harvard School of Public Health. “The guidelines committee was aware of this fact,” he says, “but they chose not to adjust their recommendations accordingly.

Wartman notes that the bulk of the fat in the American diet comes from highly refined, chemically processed vegetable oils (think corn, soybean, sunflower and safflower) that are rich in polyunsaturated fats but are also nonetheless unstable and potentially toxic. Julie Starkel, MS, MBA, RD, a functional medicine nutritionist in Seattle, agrees: “The way the molecule is formed in industrialized vegetable oils can cause free-radical damage inside the cellular membrane.”

Then there’s the problem of the science. The guidelines went to press without integrating a number of key findings from recent scientific literature, including a significant meta-analysis that suggests man-made fats and refined carbs — not saturated fat — are the main culprit behind heart disease.

Moreover, “the percentage of calories from fat in a diet has no bearing on weight loss or any other major health outcome,” says Walter Willett, MD, chair of the department of nutrition at Harvard School of Public Health. “The guidelines committee was aware of this fact,” he says, “but they chose not to adjust their recommendations accordingly.

Safe-Bet Advice: Enjoy the natural fats in whole foods and cook with minimally processed oils, like extra-virgin olive oil. Avoid heavily processed, low-quality vegetable oils (like those found in most packaged foods).

3. The New Guidelines Say: Reduce Daily Sodium Intake.

No-Nonsense Analysis

Surprisingly, no single guideline has been more publicly divisive than the seemingly simple advice to reduce sodium intake. “When the committee turned its attention to sodium, the mood in the room was quite mixed as it waded through clinical data, public health implications and food-science challenges,” says Roger Clemens, president-elect of the Institute of Food Technologists and a member of the USDA 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee.

That’s because for most people who are otherwise healthy and under age 55, cutting back on salt has little to no health benefit, and for a significant portion of the population, salt in no way affects blood pressure. (For more, see our upcoming article on salt in our October issue.) Accordingly, many experts see the current focus on sodium as a red herring likely to confound more food consumers than it helps. And they worry it may also have a number of unintended consequences, including some questionable food formulations.

“Cutting back on sodium is the government’s way of trying to protect public health, I get that,” says Starkel. “But I don’t think this guideline is going to help much.”

Processed foods currently account for 75 to 80 percent of the sodium in the American diet. And because “salt makes processed foods more palatable,” it can’t be easily eliminated from most products, says Starkel. Manufacturers will have to add other flavoring agents to compensate. Even then, most people will have a hard time staying under the current official limit of 2,300 milligrams per day, given that a single can of soup might have half the daily allotment.

Meanwhile, food manufacturers are scrambling to adjust sodium levels in all kinds of products (“low-sodium chicken nuggets” have already hit store shelves) in the hope that slapping “reduced sodium” labels on their packages will convince consumers that the products are healthy.

“Cutting back on sodium is the government’s way of trying to protect public health, I get that,” says Starkel. “But I don’t think this guideline is going to help much.”

Safe-Bet Advice: Avoid oversalted processed snacks and fast foods. But don’t assume “low-sodium” foods are healthy. Use high-quality salts (along with other herbs and spices) for home cooking.

4. The New Guidelines Say: Select lean meats and poultry. Increase intake of fat-free or low-fat dairy products.

No-Nonsense Analysis

Meat and dairy scored big points in the current guidelines. Nearly a quarter of the new MyPlate icon is dedicated to “protein,” notes Marion Nestle, PhD, MPH, author of Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health (University of California, 2002), which is a problem since most Americans read “protein” exclusively as “meat.”

The fact that the USDA has framed protein as a food group, rather than a nutrient, bothers Nestle. Especially since it tends to obscure the fact that most other elements of the plate — grains and vegetables, for example — also deliver some protein.

And the fact that the plate icon shows a side of low-fat dairy? “It’s very clear that both the dairy and beef industries spend a lot of money on lobbying,” says Willett. “And they get results.”

The guidelines around meat and dairy do not touch on the problem of industrially raised animals, which tend to be full of toxins and antibiotics, and have a less beneficial healthy fats profile than grass-fed and organic alternatives.

Many nutritionists are skeptical about the idea of promoting dairy. “We have a pandemic of allergies, asthma, IBS and many other conditions that are linked to dairy consumption,” says Kathie Swift, MS, RD, nutrition director for Food as Medicine at the Center for Mind-Body Medicine in Washington. “Cow’s milk is not an essential component of the diet for humans, so why portray it as a nutritional icon?”

Nutritionists also took issue with the USDA’s advice to choose exclusively “lean,” “fat-free” and “low-fat” animal products — a misguided slam on whole-food fats, particularly saturated fats.

Also, says Swift, the guidelines around meat and dairy do not touch on the problem of industrially raised animals, which tend to be full of toxins and antibiotics, and have a less beneficial healthy fats profile than grass-fed and organic alternatives. Because toxins tend to accumulate in fat, choosing leaner cuts of such meats may make sense for many. But for most Americans, industry-driven advice to eat more low-fat meat and dairy probably does not.

Safe-Bet Advice: Choose pasture-fed and organice animal products whenever possible. But remember there’s protein in plants, too — and know that many people do not tolerate dairy well.

5. The New Guidelines Say: Increase vegetable and fruit intake.

No-Nonsense Analysis:

Eating a diet rich in vegetables, legumes, fruits and nuts is shown to lower your risk of all kinds of chronic diseases, and to support vibrant health through countless different biological mechanisms — from fiber to phytonutrients. So if there’s one thing the new guidelines have gotten right, thank goodness, it’s emphasizing the consumption of more of these foods.

A key take-home message is to fill half your plate with vegetables and fruits, and that clarity represents a big step forward for the USDA, in Nestle’s view. She also applauds the fact that the report includes recommendations for people who are vegetarian and vegan: “When I was on the Dietary Guidelines advisory committee in 1995, we were forced to add something about the nutritional hazards of such diets.”

A key take-home message is to fill half your plate with vegetables and fruits, and that clarity represents a big step forward for the USDA.

Connecting the dots between whole foods and disease prevention is important, says Dariush Mozaffarian. Too often, the dietary guidelines focus on technical, isolated nutrient targets rather than the quality and characteristics of actual foods. The resulting advice can mislead consumers, causing them to think enriched, processed foods are as nutritionally valuable as whole, natural ones, which is virtually never the case., US, Uantio, CenRoJu, DaNationalg

“Nutrition information is pretty simple. It comes down to eating more vegetables and fruits, and eating foods in their whole, natural forms,” says Swift. “Remember, dietary confusion is perpetuated by an industry that feeds off of it. Eating well doesn’t have to be that complicated.”

Safe-Bet Advice: Make whole, brightly colored plant foods the foundation of every meal. Understand the powerful connection between plant-based eating and health.

Who Wrote the Rules

So how in the world did the government get into the nutrition business?

In the 1970s, the number of Americans with heart disease began to creep upward. In search of a fix, the federal government decided to recommend a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet. That decision led to the first dietary guidelines, called Dietary Goals, published in 1977. According to these goals, the key to a healthy diet was to eat more carbohydrates (55 to 60 percent of daily calories) and limit saturated fat (10 percent of daily calories). Americans complied. Consumption of saturated fat dropped while the amount of carbs in the American diet skyrocketed.

Along with promoting “healthy” nutrition, the department is tasked with creating a demand for the country’s agricultural products. The two responsibilities are often at loggerheads.

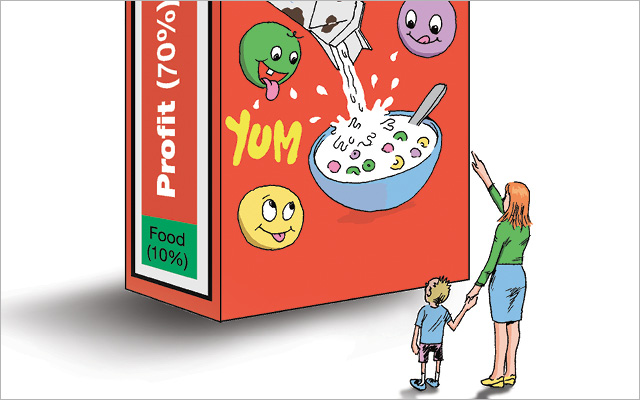

The hitch, however, is that the USDA has a serious conflict of interest. Along with promoting “healthy” nutrition, the department is tasked with creating a demand for the country’s agricultural products. The two responsibilities are often at loggerheads. And, by the basic nature of giving the thumbs up to some foods and the thumbs down to others, the USDA runs the risk of alienating the very industries it’s charged with supporting. “Every five years what comes out is nutrition science with a big dose of politics,” says Michele Simon, a lawyer who specializes in food advocacy and is the author of Appetite for Profit: How the food industry undermines our health and how to fight back (Nation Books, 2006). “Often many members on the committee have direct financial ties to the food industry.”

All of this has led to a colossal tug of war. For instance, in the 1970s, most saturated fat in the American diet came from meat, eggs and dairy. After the publication of the Dietary Goals in 1977, people curtailed their fat consumption. Sales of meat, eggs and dairy dropped. Industry bigwigs were outraged. And, later that year, under intense pressure from food lobbyists, the government revised the publication to say that consumers should “choose meats, poultry and fish which will reduce saturated fat intake.” And that kind of shenanigans is hardly a thing of the past. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, a research group that tracks money and politics, agribusiness spent more than $120 million lobbying Washington, D.C., lawmakers in 2010.

This Post Has 0 Comments