During her annual physical in October 2021, Carin Bratlie Wethern had some routine bloodwork done. A few days later, her doctor gave her a call: Wethern’s iron levels were abnormally low. She started taking iron supplements, but when levels didn’t rise much in response, her doctor decided to run some more tests.

Wethern, a theater director and child-sleep coach in Minneapolis, was shocked when she tested positive for antibodies indicating she had celiac disease, a chronic digestive and immune disorder triggered by eating foods containing gluten.

“I was like, ‘What are you talking about, celiac? I love bread. I eat bread all the time, and I feel fine,’” Wethern recalls. But an endoscopy revealing damaged villi in her digestive tract confirmed the diagnosis. Wethern’s days of consuming gluten were over.

Gluten is a protein found in some grains, such as wheat, barley, and rye. It contains a variety of indigestible fragments (or peptides) that can stimulate a strong immunological response in genetically susceptible people.

For those with celiac disease, gluten sets off an autoimmune reaction that can destroy the villi — the tiny fingerlike projections that line the small intestine. Celiac can lead to iron deficiency, a form of anemia, because the part of the intestine damaged by gluten is also responsible for iron absorption.

“I’ve always prided myself on being an enthusiastic eater of foods of all kinds. Now I can’t be that person anymore,” Wethern says. “It’s really heartbreaking.”

Still, it beats the alternative. If left unaddressed, celiac disease can lead to the development of other autoimmune disorders, like type 1 diabetes and multiple sclerosis, as well as other health conditions, such as anemia, osteoporosis, infertility, epilepsy, migraines, heart disease, and intestinal cancer.

The Rise in Celiac Disease

Serology-based prevalence studies report that between 1 and 2 percent of the global population has celiac disease, though many of these cases remain undiagnosed. Distribution is fairly equitable across the continents, with marginally higher prevalences in Europe and Asia.

The disease tends to affect women more often than men and children more often than adults. According to the Celiac Disease Foundation, rates have been increasing by about 7.5 percent per year for several decades.

“The increase in celiac disease is partially due to the increase in awareness and testing, but there has also been a true increase in the prevalence over time,” says Alessio Fasano, MD, director of the Center for Celiac Research and Treatment at Massachusetts General Hospital and author of Gluten Freedom. “The incidence is doubling every 15 years.”

What’s behind this rise?

“We don’t know, but it’s likely because we’re derailing from evolution’s plan in terms of having friendly interactions with the ecosystem — the soil, air, and water,” Fasano explains. “Chemical pollution and other factors impinge on our gut microbiome, which determines if, when, and why our genes are put into motion.”

“Chemical pollution and other factors impinge on our gut microbiome, which determines if, when, and why our genes are put into motion.”

Celiac does have a genetic component, but not everyone with the genes for it develops the condition. Up to 30 percent of us carry a gene that puts us at greater risk, though it only increases the risk from 1 percent (the risk for the general population) to 3 percent. The likelihood of developing celiac does go up substantially for those who have a parent, sibling, or child with the disease.

Onset can occur during childhood or adulthood. Children are more likely to have digestive symptoms, such as abdominal bloating and pain, diarrhea, constipation, or nausea. Adults with celiac may also display these symptoms or others, such as fatigue, brain fog, headaches, depression, anxiety, skin rashes, or joint pain. Some, like Wethern, don’t notice any symptoms at all.

People with celiac disease produce antibodies called anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies. “Transglutaminases are enzymes that help bind proteins together and are also involved in the digestion of wheat in the gut,” explains functional-medicine practitioner and clinical researcher Datis Kharrazian, PhD, DC, MS, FACN, author of Why Isn’t My Brain Working?.

In people with celiac, gluten triggers immune reactivity to the type of this enzyme that’s located in the intestinal lining. For this reason, gluten must be strictly avoided for the rest of the person’s life or symptoms will recur.

Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity

To make matters more complicated, someone may be sensitive to gluten without developing full-blown celiac disease.

Gluten sensitivity occurs on a spectrum, with celiac representing the most severe end. On the other, there’s non-celiac gluten sensitivity, which can range from mild to intense. “We’re seeing dramatic increases in the number of people sensitive to gluten in the United States,” Kharrazian says. “Research shows gluten sensitivity has risen sharply in the last 50 years.”

So, what’s the difference between celiac and gluten sensitivity? “Patients with gluten sensitivity develop an adverse reaction when eating gluten that does not usually lead to small-intestinal damage,” Fasano explains.

“Patients with gluten sensitivity develop an adverse reaction when eating gluten that does not usually lead to small-intestinal damage.”

While there can be overlap with some of the symptoms of celiac, the overall clinical picture of non-celiac gluten sensitivity is generally less severe. “Non-celiac gluten sensitivity is a pretty mysterious space we occupy, in which people experience symptoms that go away or are improved when they eliminate gluten,” says functional nutritionist Jesse Haas, CNS, LN. “That data may be validated by lab testing, but it’s not always measurable in an immune reaction, which makes it kind of hard for the general public — or even the medical establishment — to trust that it’s valid.”

Like celiac disease, a non-celiac gluten sensitivity triggers a reaction from the immune system. The difference is that when someone with a sensitivity eats gluten, their immune system doesn’t attack the villi in the small intestine; it goes after the gluten molecules themselves, producing specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to combat them. Many tests claim to identify sensitivities by testing for IgG antibodies. But false positives are common, and a test may indicate that someone is creating IgG antibodies against a food that isn’t causing any negative reactions.

“We and many others are working diligently to identify the biomarkers that will tell us if you have gluten sensitivity or you do not,” Fasano says. “We have these biomarkers for celiac disease; we have biomarkers for allergies; but we don’t have them yet for non-celiac gluten sensitivity.”

For now, the most reliable approach is to observe the effects of gluten — and its absence — on the body. “We have to show a relationship between exposure and symptoms,” Fasano says. “When you have gluten, you get worse. When gluten is out of your system, you get better. That’s how we make the diagnosis of non-celiac gluten sensitivity.”

Signs of gluten sensitivity can be broad, including symptoms of systemic inflammation, such as joint pain, rashes, and fatigue. “It can also be ambiguous mental health symptoms like brain fog or memory challenges, depression, anxiety, or even neurological symptoms — there are reports of seizure disorders being resolved on gluten-free diets,” says Haas. (For more on checking your gluten sensitivity, see “How to Conduct a Gluten Experiment” below).

For people without celiac disease, gluten sensitivity can change over time, Fasano notes. “With non-celiac gluten sensitivity, there is a possibility you may eventually change the level of sensitivity to gluten or even grow out of it. This is not the case with celiac disease, which is a lifelong condition.”

Haas ate a strict gluten-free diet for eight years to address her own digestive issues. But for the past few years, she’s been eating gluten-containing foods a few times a week, with far less reactivity than she experienced in her 20s.

“If you can address intestinal permeability, shore up the boundaries of the small intestine, and improve its ability to digest and absorb nutrients, then it’s less impactful when you eat the same foods that gave you trouble before, as long as you’re not eating them to such a great extent,” Haas explains. “It’s about improving the resilience of your system overall.”

Unfortunately, there’s no wiggle room for those with celiac disease. They will likely need to avoid gluten permanently, Kharrazian says, as well as foods that are cross-reactive. (The body’s immune system can confuse cross-reactive foods for gluten; they include corn, oats, dairy, rice, and yeast.)

People with autoimmune conditions may also do well to steer clear of gluten for the long term. (More on this later.)

The Gluten–Inflammation Connection

Gluten-containing foods are removed during almost any food-elimination protocol. This is because even if someone isn’t technically sensitive to gluten, the protein can still contribute to inflammation.

Eating gluten triggers a specific inflammatory process in the small intestine called the zonulin pathway, Haas explains. Zonulin is the protein that regulates the opening and closing of the intestinal barrier. This protein plays a leading role in the development of leaky gut — and gluten sparks its release.

When food particles slip between the loosened junctions of the gut lining and leak into the bloodstream, the immune system is activated by the foreign material, and inflammation results. (Learn more about leaky gut at “What Is Leaky Gut?“)

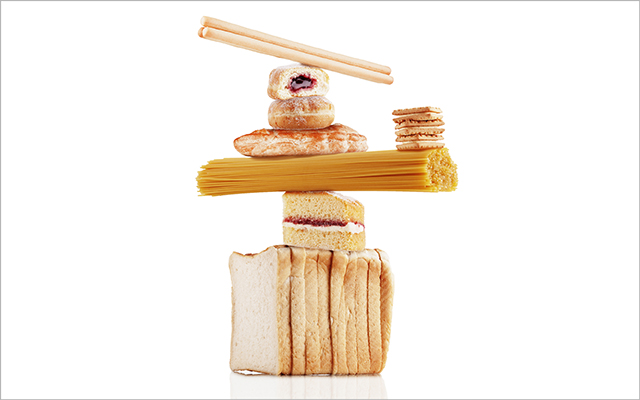

“If we have cereal or a bagel for breakfast, a sandwich for lunch, and pasta for dinner, that pathway is getting kicked into gear multiple times a day,” says Haas. When we follow that pattern for days, weeks, and years, we can end up with chronic systemic inflammation and all the vague symptoms, such as joint pain and brain fog, that can accompany it.

“If we have cereal or a bagel for breakfast, a sandwich for lunch, and pasta for dinner, that pathway is getting kicked into gear multiple times a day,” says Haas. When we follow that pattern for days, weeks, and years, we can end up with chronic systemic inflammation and all the vague symptoms, such as joint pain and brain fog, that can accompany it.

The very molecular structure of gluten challenges our digestive system. Think of a protein strand as a pearl necklace, says Fasano: Our digestive enzymes break the necklace into pieces called peptides, which can be absorbed by the intestine and used as fuel or building blocks for new proteins.

Most proteins we ingest can be completely disassembled into individual amino acids. But not gluten. “While any ordinary peptide from a foodstuff other than gluten can be dismantled by intestinal enzymes within 60 minutes, those derived from gluten can resist digestion for as long as 20 hours,” Fasano notes. And research has shown that our digestive enzymes can leave large fragments of gluten intact.

“This is why dairy also comes up in elimination diets, because casein (one of the proteins in dairy) has a similar vibe as gluten — they’re just really [dense] molecules,” Haas says. If the digestive tract is inflamed or compromised, it’s harder for the body to break down these proteins.

“Eliminating them for a time makes it easier for the body to digest and absorb nutrients because the body isn’t inflamed in response to the presence of those molecules in the digestive tract.”

Gluten and Autoimmunity

Another area of concern with gluten involves what’s called molecular mimicry. Essentially, gluten’s sequence of amino acids resembles that of some of the body’s own tissues, particularly the thyroid gland and nervous tissue.

“When you’re sensitive to gluten, the immune system produces antibodies to tag it for destruction,” Kharrazian explains. “However, because gluten has amino acid sequences similar in structure to some amino acid sequences in nervous tissue, the immune system may accidentally produce antibodies to nervous tissue whenever you eat gluten.”

In this case, gluten sensitivity could lead to an autoimmune attack against the brain or other parts of the nervous system. Immune reactions to gluten can also break down the blood–brain barrier, leading to what some integrative practitioners call leaky brain. The condition can allow pathogens to enter the brain and increase the risk of autoimmune reactions there and throughout the nervous system.

Because gluten can also mimic thyroid tissue, people with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis may benefit from avoiding gluten as well.

Because gluten can also mimic thyroid tissue, people with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (an autoimmune condition in which the immune system attacks the thyroid) may benefit from avoiding gluten as well. “Some people with Hashimoto’s have gluten sensitivity as a driving force leading to the auto-attack on the thyroid, unlike in celiac, in which everyone affected has gluten as the environmental trigger,” Fasano notes.

Confidently identifying those whose autoimmune conditions will benefit from a gluten-free diet will be easier when researchers find biomarkers of non-celiac gluten sensitivity. “How gluten affects you depends on your genetic makeup and how you express inflammation and autoimmune flare-ups,” Kharrazian notes. Still, “clinically, we see autoimmune patients do best avoiding gluten permanently.”

Gluten Elimination or Moderation?

For those who don’t have an immunological reaction to gluten, is it worth keeping in their diet? “Gluten only needs to be excluded if you’re clearly part of the spectrum of gluten-related disorders,” Fasano says, adding that eliminating gluten probably isn’t worth the time or effort for those with no sensitivity.

Still, he advocates moderation. “A true Mediterranean diet will include gluten, but it’s not the huge amount you see in the United States.”

Fasano also notes that farming and food-preparation processes are factors. “You can induce an immune response and make the immune system belligerent, not just because you’re exposed to the grains, but because you’re also exposed to whatever comes with the grains,” he says.

That may help explain why some people who have trouble with gluten in the United States find they’re able to better tolerate bread and pasta abroad.

Agricultural chemicals such as glyphosate, found in the herbicide Roundup — which is widely used on wheat in the United States and is associated with leaky gut — are much more strictly regulated in Europe. And commercial bakers there typically let dough rise overnight rather than utilizing the accelerated industrial process in the United States, which doesn’t give yeast a chance to dismantle some of the peptides in gluten.

For many of us, the gluten question isn’t black and white — or static across time and place. It’s one of the many gray areas we get to occupy with awareness, flexibility, and moderation.

Kharrazian agrees that not everyone needs to avoid gluten. “But if you have a chronic health condition, it’s a factor to consider. And everyone would likely benefit from minimizing grains high in glyphosates.”

Haas also encourages a moderate approach to consuming gluten — even for those who seem to tolerate it well. “Because that darn zonulin pathway is so pervasive, I don’t know that eating wheat super habitually is beneficial to anyone,” she says. “Variety is so important for human health, so we don’t want to consume anything multiple times a day, multiple days in a row, for years on end.”

Sprouted and fermented gluten-containing grains can be easier to digest. And some varieties of heritage wheat — such as Turkey Red wheat — are better tolerated due to their lower gluten content. (To learn more about heritage grains, see “The Heritage-Wheat Renaissance“.)

For many of us, the gluten question isn’t black and white — or static across time and place. It’s one of the many gray areas we get to occupy with awareness, flexibility, and moderation.

How to Conduct a Gluten Experiment

If you’re wondering whether gluten is contributing to unpleasant symptoms for you, it may be time to try an experiment. Functional nutritionist Jesse Haas, CNS, LN, suggests starting with a tally of any baseline symptoms you’re hoping to evaluate (fatigue, brain fog, joint pain, depression, diarrhea, for example). Then stop eating gluten-containing foods (plus oats, which can be cross-reactive with gluten) for three months.

“I think it takes three months of elimination to fully understand gluten’s effects on your body. It takes a long time for those systemic symptoms and inflammation to resolve.”

At the end of the three-month trial, hopefully you’ll notice improved symptoms, she says. “When your energy is back, your brain is clear, your mood is stabilized, and your digestion is cool as a cucumber, then it’s time to start reintroducing.”

When reintroducing gluten, go for pure ingredients in large doses to maximize the feedback from your body, suggests Haas. Start by eating half a cup of cooked oats a few times a day for a couple of days. “Really make it clear to your body: I’m eating this thing; what are you going to say about it? Then do some self-inventory and see what you notice about your health,” Haas says. “Are those symptoms the same, a little worse, a lot worse? That will tell you whether that ingredient is tolerated by your body or not.”

Repeat the process with rye, then wheat, focusing on foods that contain only that single ingredient so you’re not mixing variables: For example, skip the cheese and sour cream on your wheat tortilla; if you react, you’ll know the cause.

What if symptoms arise upon reintroduction? “That’s where we get to decide for ourselves,” says Haas. “Now we know the consequences and we can decide if it’s worth it, and how often. That’s personalized nutrition.”

This article originally appeared as “Gluten? It’s Complicated” in the May 2023 issue of Experience Life.

This Post Has One Comment

You mentioned that agricultural chemicals that are added or used in the US can make people more gluten sensitive in the US compared to Europe. What about the types of seeds used in planting various types of wheat, barley and rye? How do seeds compare between the US and Europe? And what about GMO seeds? Have you heard of any research done specifically on seeds themselves?